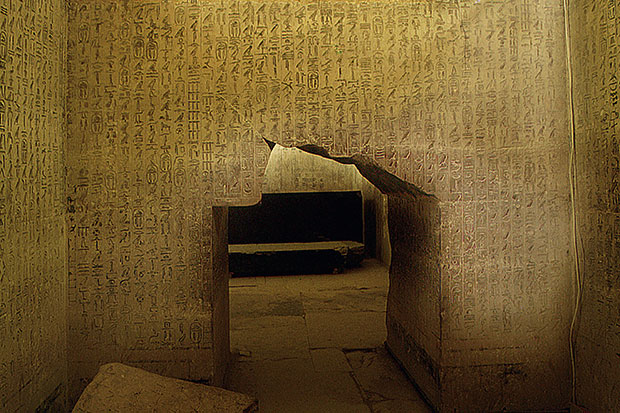

When the Saqqara pyramids were opened in 1880, the chamber walls were found to be covered in hieroglyphic writings, and these texts have been a subject of discussion among Egyptologists ever since. What do they mean? What do they represent? What do they tell us about the religion or the cosmology or the worldview of a culture that can sometimes seem incomprehensibly far from our own?

Taking issue with the scholars that have come before her, Susan Brind Morrow uses this fascinating, challenging book to demonstrate her view that the message on the walls is poetic, timelessly meaningful and sophisticated. Part of her thesis involves simply stripping away the long-held assumption that there must be a mythology behind what is written, suggesting rather that what we’re seeing instead is poetic metaphor (that ‘silver eye’ of the title is the moon, of course). And sometimes, when you’ve cast aside your mythological obsessions, a literal reading might make more sense. Sometimes an owl is just an owl. This is a complex, dense, clever book, but it’s arguing a case for simplicity and clarity.

That’s not to say that the writing Brind Morrow analyses for us is itself unsophisticated; merely that a century of Egyptology has seen its interpretation overlaid with things that aren’t actually there, things that need to be peeled back to look afresh at what she argues is carefully structured poetry. The texts use all kinds of recognisable writerly techniques — there’s a mastery to them, an expertise — with puns and seemingly intentional ambiguities and double meanings (the image of a lion is also the word for a ‘gate’, giving each gate reference a little added dangerous thrill). They play on sound and sense, and on the double-duty whereby hieroglyphs represent simultaneously concrete and metaphorical things and sounds (that picture of an owl is an owl and all that an owl represents, but it’s also an ‘m’).

There’s no mythic narrative to connect it to, but there’s pleasingly complex metaphor. There’s onomatopoeia (wepwawet is the cry of the coyote, shu the word for air and wind), and there are riddles that depend on sounds or on the interrelation of the carefully arranged physical placing of the figures on the wall — riddles that might resolve into, for example, a star map.

Earlier misreadings are blamed on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of Egyptian religious thought. Where Brind Morrow’s own reading is poetic and coherent, her predecessors’ have frequently been neither, as scholars have wrestled to make the hieroglyphs fit into their own distorted cultural expectations. She makes her clarity seem incontrovertible. ‘How’, she asks — after positing her quite uncomplicated explanation of a line – ‘can this simple image, with a kind of stately loveliness expressed by the simplicity of the hieroglyphs themselves, be misconstrued to mean the anus of a screeching baboon?’ It’s a reasonable question.

Alongside her exegesis of the texts, Brind Morrow also includes a full translation of her own. Where the commentary is a piece of detailed practical criticism, this is the work of a poet translating poetry. But translation, too, is interpretative and critical; translation, too, is a reading of, and a comment on, the thing that it is rendering to its new readers.

Personally, being inclined to matters linguistic, I enjoy parenthetical explanations of the uses of vowels, or of the workings of verbs (though you may find your pleasures elsewhere). The code-breaking aspect is satisfying, too. But it’s not a book for the faint-hearted. Brind Morrow’s intelligence is bracing, and entirely uncompromising. While lay readers may be flattered by the assumption that it’s surely as evident to us as it is to her, is a reviewer allowed to make an admission that — with the greatest of efforts — just occasionally he wasn’t able to understand the book under review, I wonder?

But even when it’s at its hardest, demanding re-reading and re-reading, The Silver Eye is a book filled with poetic pleasures and intellectual stimulation. The rewards of revelation come slowly, and they need to be earned. As Brind Morrow writes, describing the experience of reading the hieroglyphs: ‘Repetition draws the mind into an evolution of meaning, as though turning the object in the light.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17.00. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in