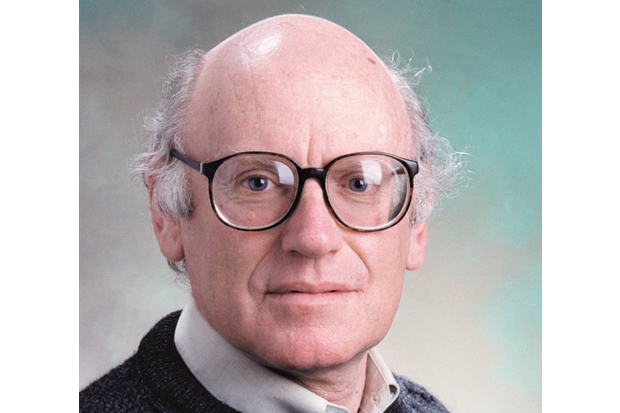

The distinguished Australian historian John Hirst has sadly died at age 73. Those who knew him at La Trobe University in Melbourne, where he held appointments from 1968 until his retirement in 2006, have remembered his kindness and decency as a colleague and mentor, and his talent and originality as an historian and public intellectual. Most of us, however, knew him through his written works.

Hirst was never afraid to express an opinion, or to express it well. He was something of an outsider – ‘gadfly’ was the word often used – which in academia is usually shorthand for a suspected conservative. Such labels tend to fail those who are genuinely intelligent. He had voted Labor and was a committed egalitarian, but also lamented that, as he put it in 2010, ‘Historians sympathetic to the Left had determined the terms in which political history is discussed in this country… Our political history becomes much more interesting once you throw off the Labor view of it’.

Which process comes first – clear thinking or clear writing – is a fascinating question, but it’s enough to say for now that Hirst was both one of Australia’s most eloquent historians and our most unique. He wrote for the nation, not for fellow academics, and he never had to rely on obscurantist prose to make his interpretations of the past seem more interesting than they actually were. In 1988, another famous voice of dissent, Clive James – no friend of academics – observed that ‘Australian journalists have written better history, or at any rate better-written history, than the historians, among whom Geoffrey Blainey is exceptional in possessing an individual style’. We can only hope that James eventually discovered some of Hirst’s books.

As the debate over an Australian republic barges uninvited into our national conversation again, I suspect Hirst’s contributions would’ve been the only ones worth reading on the pro-republican side. He came to believe that republicanism of the 1990s had it all wrong: whereas the Australian Republican Movement had presented the image of a nation that had yet to mature, Hirst later felt that this was an argument of the cosmopolitan Left. Instead, he would contend in retrospect, the people should’ve been given a republican movement that recognised Australia already was a nation. The current leader of the ARM, former rugby player Peter FitzSimons, seems to want to create a republic in the image of an airport souvenir shop – this is taking the nationalist approach too far. Hirst’s understanding of nations and nationalism was rather more subtle, and his arguments in favour of a republic would’ve provided some lucidity in a debate that is frequently and embarrassingly absurd.

It’s become unpopular in academia to speak of national characteristics; the cultures to which people belong are always and everywhere different, but nations are composed of individuals who merely believe they’ve something common. Hirst, however, was never afraid to admit that nations and cultures might overlap – he often used the example of tourism to demonstrate the point. International travellers, of whom Australia exports vast numbers, ideally understand that behaviours acceptable in one country might not be acceptable in another. Hirst joked that if you believe there is no national identity and culture that distinguishes, for instance, the Japanese from Australians, you were more than welcome to see how you fare acting in Japan as you might in Australia.

In fashionable circles, however, it’s verboten to suggest Australians have distinctive characteristics or Australia its own culture. Hirst was keenly aware of this, and often prefaced his discussions of Australia’s national characteristics with an apology to his colleagues who dismissed such talk. It was a rare concession to accepted wisdom. If he had apologised for all the ways in which he transgressed the party line, he would’ve never gotten around to writing anything worth reading; academic history needs fewer apologies and more assertions. Thankfully, Hirst wasn’t so insecure as to be always searching for a footnote to validate his point of view, nor did he constantly announce that his was just one interpretation among many.

One view of Australian history that he asserted was that our immigration story was mostly positive. Hirst disagreed that Australia’s treatment of immigrants has been largely deficient. Australia had taken in vast numbers of migrants from across the world in the postwar era. There had been, and always will be, some tensions, but the Australian immigration programme had been far more successful in this regard than in other countries. It pained many intellectuals, he had teased, that migrants had done quite well over successive generations, and it was a constant frustration to critics that there weren’t more actual racists. The success was mostly to do with Australians, and not their government: ‘What happened on the ground does not relate closely to policy,’ Hirst said. ‘You would be closer to the truth if you assumed that developments on the ground were the opposite of policy.’ It was an argument typical of his heterodox style.

Hirst had a keen eye for sense and nonsense and expressed his view of the world with a skill that matched the standards of any of our great literary stylists. Academic historians can learn much about the historian’s craft from his example, just as Australians can learn much about themselves from reading his books and commentary. Original, brave, and talented, we will all sorely miss his unique voice and valuable contributions to the national conversation. Vale, John Hirst.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in