Philip Hensher, the thinking man’s Stephen Fry — novelist, critic, boisterously clever — begins his introduction to his two-volume anthology of the British short story with typical gusto. ‘The British short story is probably the richest, most varied and most historically extensive national tradition anywhere in the world.’ Take that, ye upstart Americans, with your dirty realism and your New Yorker swank! Read it and weep, ye Johnny-come-latelys! Look to your laurels, Chekhov and Carver. Jorge Luis Who? Maupassant? Bof!

And there’s more — much much more. In a short introduction of just 35 pages Hensher sets out his stall, settles some old scores and convincingly establishes himself as a world authority on the subject of the short story, even though these days his own books — The Northern Clemency, The Emperor Waltz — tend to be vast baggy monsters with grand state-of-the-nation ambitions. (Though it’s worth remembering that way back last century A.S. Byatt concluded her Oxford Book of English Short Stories [1998]with Hensher’s ‘Dead Languages’ — quite a compliment, and well deserved. Hensher now dutifully returns the compliment, dedicating his Penguin Book to Byatt, and including one of her own stories, naturally.)

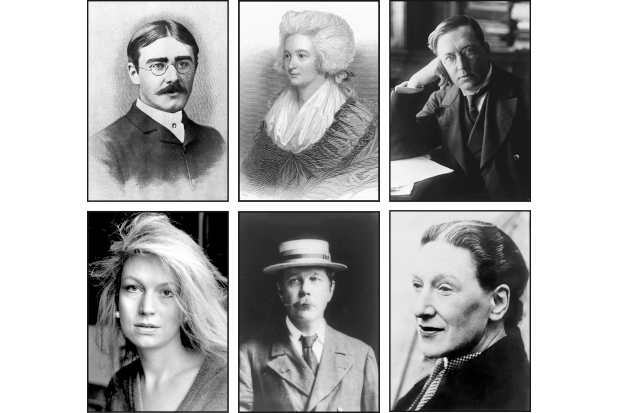

If you buy both volumes — Defoe to Buchan and Wodehouse to Zadie Smith — and you absolutely should, because as books, as objects, they are as good as it gets, quality paper, thick-set, sewn, and handsome enough to hang on a wall — you get the same introduction twice. Fortunately it’s worth rereading. The second time around you start to notice the tiny little pricks and barbs that you missed the first time. Hilary Mantel gets a little dig (‘The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher’ is ‘not a very accomplished piece of work’). There is short shrift given to abstruse arguments and ‘restrictive explanations’ about the short story: Hensher blames such nonsense on ‘the rise of creative writing as an academic discipline’. (Hensher is in fact a professor of creative writing at Bath Spa University, so presumably partly responsible.)

As for his definition of the ‘British’ short story, it is, as it should be, delightfully idiosyncratic. The work of Elizabeth Bowen — born in Ireland, lived in England — is in, because her ‘subject seems indubitably British’, whatever that means. But Katherine Mansfield — born in New Zealand, lived in England — is out because there is a ‘strong movement’, apparently, to regard writers like her ‘as conferring merit on their place of birth rather than their residence’ — which sounds rather like one of those silly academic arguments worth giving short shrift to, but never mind.

Hensher’s tentative definitions of what characterises a typical British short story is perfectly unobjectionable: according to him the BSS is playful, it is ‘rumbustious, violent, extravagant, fantastical’, but also capable of ‘withdrawn exactitudes’. That just about covers everything. You could probably argue that these are characteristics of all short stories, and possibly all literary fiction in all countries at all times. It would be an interesting argument, if one that Hensher would undoubtedly win: he doesn’t strike one as someone to be bested.

Just whatever you do, don’t get him started on short story competitions. He despises short story competitions (with the notable exception, presumably, of the V.S. Pritchett Memorial Prize, for which he was a judge earlier this year). Competitions, according to Hensher, produce solipsistic drivel. They encourage work that lacks ‘real energy’, which Hensher doesn’t define but which is presumably quite unlike ‘unreal energy’ and which seems to have something to do with ‘the social interaction which is the proper subject of fiction’. Also, prizes are humiliating: ‘No one… ever invited, or required Conan Doyle or V.S. Pritchett or Kipling or P.G. Wodehouse to put on a dinner jacket and shake the hand of a retired academic before they could receive a cheque for a short story.’

He’s got a point. He also has a solution: pay writers proper money for their stories, so they don’t have to enter competitions. In 1914 W.W. Jacobs could expect to be paid by the Strand magazine about £350 for a short story, not far off the annual income of a family doctor. One hundred years later to be paid £350 for a short story would represent an unimaginable fortune. Hensher’s not naive enough to think this situation could change overnight, but he does have an interesting suggestion:

If an ordinary newspaper took to publishing, once a week, a short story and paying the same that it currently pays for the celebrity interview that fills the same space, then the short story in all its forms would soon return to the energy and inventiveness that it possessed until recently.

If you are reading this review and you happen to be a newspaper proprietor, an editor, or someone wielding great power and influence, take note: this is a good idea.

And as for the stories — there are classics, rarities, unconsidered trifles, and only the occasional dud. The book begins with Defoe’s ‘A True Relation of the Apparition of Mrs Veal’, which is tiresome, but picks up immediately with Swift’s ‘Directions to the Footman’, which is an early version of the ever-enjoyable short-story sub-genre of story-as-form-of-ironic-instruction. (‘When your master and lady are talking together in their bed-chamber, and you have some suspicion that you or your fellow-servants are concerned in what they say, listen at the door for the publick good of the servants.’)

And so one reads on and on, through all 1,500 pages, through Hannah More and Thackeray and Conrad and Wells and M.R. James, all the time wondering at the range and quality of these tiny little things, some of them no longer than a few pages. (Hensher doesn’t go in for ‘short’ shorts or flash fiction.) Who’d have thought they could squeeze so much into them? God, you remember, Saki’s good. But so is Stacy Aumonier! Stacy Aumonier: you remember Stacy Aumonier? No, me neither. And I’d definitely never even heard of T. Baron Russell, Jack Common or Leslie Halward. But James Hanley, of course! And Shena MacKay! And whatever happened to Candia McWilliam (represented here by the beautiful, tragic ‘The Only Only’)?

In any review of an anthology the reviewer is duty bound to mention unjust exclusions and unwise inclusions. Being a diligent and forceful sort of chap, Hensher foresees these objections and gets his response in first. He admires work by David Rose and Penelope Gilliatt, he says, of course he does, but decides not to include them in the book, ‘with regret’, which is a shame — it would have been such a treat for readers and a boon for the writers, too little known and appreciated.

We get Ian McEwan and Zadie Smith instead, whose work is perhaps more familiar. Oh well. ’Twas ever thus. Fame the perpetual motion machine. But Christine Brooke-Rose gets a look in, the experimentalists’ experimentalist, as does Georgina Hammick, a total one-off, and Adam Marek, with ‘The 40-Litre Monkey’, which is as good as anything else here, by a writer little known, and which helps guarantee in the end that Hensher’s anthology is bigger, better and broader in several senses than anything else currently available.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

The Penguin Book of British Short Stories Volume I: From Daniel Defoe to John Buchan, £20 and Volume II: From P.G. Wodehouse to Zadie Smith, £20 are available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033. Ian Sansom’s books include Paper: an Elegy, The Truth about Babies and two ‘County Guides’ detective novels, The Norfolk Mystery and Death in Devon.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in