‘Wherever the British settle, wherever they colonize,’ observed the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, ‘they carry and will ever carry trial by jury, horse-racing and portrait-painting.’ This doesn’t sound like a bad set of cultural baggage, even for those who don’t care for the races. There is clearly a lot to be said for trial by jury, and portraits make up the most enjoyable — in fact, downright humorous — section of Artist & Empire, a curious new exhibition at Tate Britain.

Not, of course, that Tate approaches this subject in a playful spirit. At the entrance, a hand-wringing text declares that the British empire’s ‘history of war, conquest and appropriation is difficult, even painful to address’. Even so, it points out — correctly — that the whole sorry business had a considerable effect on art, in Britain and elsewhere.

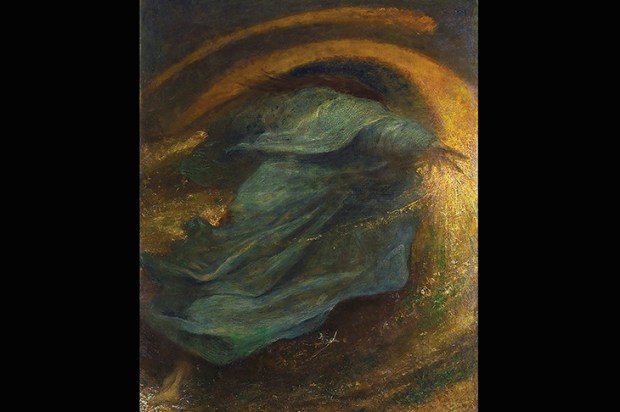

The show turns out to be a good deal more fun than this introduction augurs because of the intrinsic charm and, quite often, absurdity of the objects on show. A good deal of space is taken up by grand Georgian and Victorian paintings on imperial themes. Among these first prize for hilariousness goes to Edward Armitage’s ‘Retribution’ (1858), which depicts a burly, governess-like figure of Britannia throttling a full-grown Bengal tiger in revenge for the Indian Mutiny. This represents another game effort on Tate’s part — following Sculpture Victorious earlier in the year — to find something to do with the 19th-century paintings previously relegated to the storeroom (or perhaps the officers’ mess).

There are much more engaging, and better, things to be seen. The flora and fauna of the empire are depicted in delightful images such as the Indian artist Shaikh Zain ud-Din’s ‘Common Crane’ (1780), a lanky bird with enormous feet, twisting its neck around to peer at the viewer with one sharp little eye. George Stubbs’s ‘Cheetah and a Stag with two Indian handlers’ is an out-and-out masterpiece, apparently recalling the moment when the big but timorous cat tried to run away rather than take part in a deer hunt.

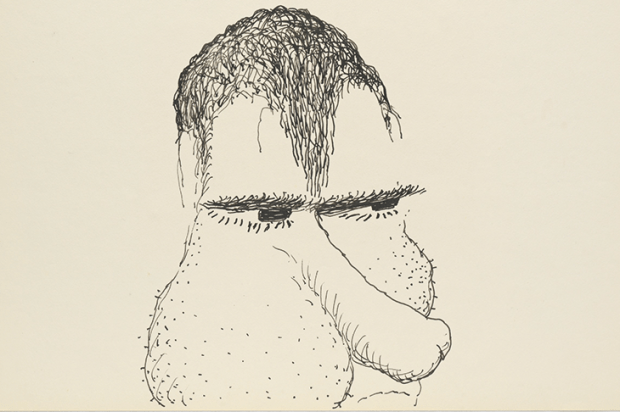

Similar panache, plus a hint of fancy dress, is to be found in the portraits. Van Dyck’s full-length of an early nabob, the hefty ‘1st Earl of Denbigh’ (1633–4), strides along in Indian dress, with palm tree and attendant in the background. In John Singer Sargent’s portrayal, ‘Sir Frank Swettenham’ (1904), the first Resident-General of Malay States, wears a uniform as gleaming white as hotel napery in a setting worthy of Louis XIV, but looks as though he might be more at ease in the club bar.

Elsewhere — an introductory section of maps, for example — the exhibition is a bit thin, visually (the ones in which a strident imperial red covers much of the globe looking the jolliest, although that is not the curators’ point). Art & Empire poses a question for the new director of Tate Britain, soon to arrive: whether to carry on with this lowering blend of art and social history — or mount more exhibitions like the marvellous Frank Auerbach, currently on show upstairs. Time for a change of policy on Millbank, I would say.

Meanwhile, at the Queen’s Gallery there is Masters of the Everyday. This is a display of some — just some — of the Dutch pictures in the Royal Collection. Nonetheless, it contains no fewer than four Rembrandts (the Queen has more of those) plus enough Jan Steens to make up a mini-retrospective, several fine Pieter de Hoochs and a single, superb Vermeer.

‘The Music Lesson’ (c.1662–5) was bought by George III as part of a job lot from Consul Smith of Venice. At the time it was attributed to Frans van Mieris, and even if it had been labelled ‘Vermeer’ no one would then have been interested. Now it’s one of the best known pictures in the world, and subject of a film, Tim’s Vermeer.

Paintings have their fates; so do their owners. The greatest contributors to the Royal Collection were George IV and Charles I, both disastrous rulers. In Britain at least there seems to be an inverse relation between artistic taste and political nous. This may explain why the mighty empire did not produce very much in the way of good art.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in