Listen

The first thing you need to know about the new sexual revolution isn’t how to do it: it’s how to talk it. Confining yourself to terms such as straight, gay and bisexual — which once, perhaps, covered most of what you thought you needed to know about a person’s orientation — is indicative of adherence to a ‘binary’ view of sexuality. It is fast becoming the equivalent of walking around in plus-fours, peering at human desire through a monocle.

These days, people — particularly those in their teens and twenties — are declaring themselves ‘pansexual’, ‘genderfluid’ and ‘genderqueer,’ which means they won’t be confined to the old folks’ dreary, black-and-white view of attraction or gender. Take Miley Cyrus, for example, the US pop singer and former child star of Disney’s Hannah Montana. Up until recently, the adult Cyrus might chiefly have been defined as a roaring exhibitionist. On one memorable occasion in 2013, her suggestive gyrations with a giant foam hand cowed even the confidently sleazy pop star Robin Thicke: next to Miley onstage at the Video Music Awards, he gradually took on the demeanour of an anxious Edinburgh dowager.

Then, last August, Cyrus came out as ‘pansexual’: defined as an attraction ‘towards people of any sex or gender identity’, including those who are ‘transgender’ or ‘genderqueer’. A transgender person, as many now know, is someone who does not identify with their biological sex, and wishes instead to unite their form with their feelings — for example Caitlyn Jenner, the former US Olympic athlete once known as Bruce; or Kellie Maloney, originally the boxing promoter Frank. Although both were men who became women, the travel can of course be in either direction.

Yet sometimes individuals want to climb out of one gender, but not straight into another, arriving at the third way: ‘non–binary and genderqueer’. Some days, such folk say, they identify as a man and on others as a woman. Or they might never feel like either, but remain in a genderless space between the two. Some genderqueer people insist on being called the singular form of ‘they’ rather than ‘he’ or ‘she’. The polite thing when in doubt, apparently, is to check first: which pronoun do you prefer?

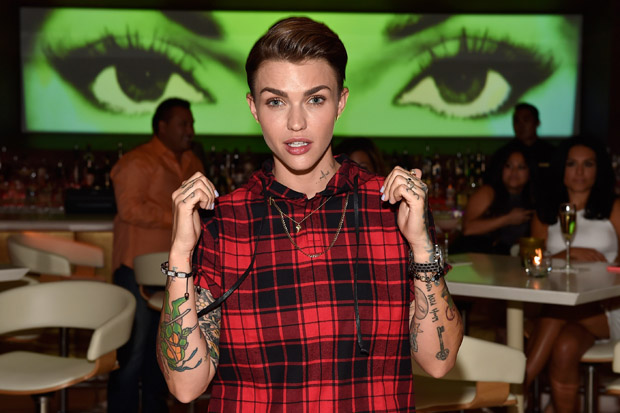

If Miley is potentially attracted to men, women, trans and genderqueer people, she’s not alone: the model of the moment, Cara Delevingne, is currently stepping out with her girlfriend St Vincent — birth name Anne Clark — an avant-garde musician and songwriter. St Vincent is fine-boned and ethereally beautiful, like the female heir to David Bowie in his Ziggy Stardust years, and says: ‘I believe in gender fluidity. I don’t really identify as anything.’ Then there is Ruby Rose, the Australian model and star of the US prison series Orange Is the New Black, who combines a strikingly pretty face with a cropped quiff and two armfuls of tattoos. Rose, who is lesbian and describes herself as ‘very genderfluid’, has triggered crushes in legions of erstwhile heterosexual women, many of whom are publicly vowing on social media, ‘I would go gay for Ruby Rose.’ Some lesbians disapprove, arguing that sexual orientation is not something you can take on and off like a shirt: yet according to a recent YouGov survey, almost half of young people between 18 and 24 in the UK don’t consider themselves exclusively straight or gay.

Mainstream fashion is muscling in. This season Fendi has chosen the couture muse Amanda Harlech as the face of its menswear collection. Harlech is pictured on horseback, wearing a black moustache and looking like the lost son of Salvador Dalí. The creative director of menswear, Silvia Venturini Fendi, has suggested that the department will soon blur with womenswear: ‘No more classification. No more boundaries. No more pink for girls.’

Is this new? Not in itself, no. If every generation thinks that it invented sex, then much the same holds true for androgyny. There have always been those who yearned, for various reasons, to elude the restrictions imposed by biology. Such figures are present in myth and art, from the Greek god Aphroditus — clad and shaped like a woman save for a discreet penis — to Shakespeare’s cross-dressing casts. In some eras such behaviour posed a risky challenge to authority: Joan of Arc’s political enemies used her habit of dressing as a man as the technical pretext for her execution.

Other times proved more indulgent: the society poet Natalie Barney, for example — perhaps the most exciting thing ever to come out of Dayton, Ohio — was in some ways a trailblazer for the ‘genderfluid’ youth of today. Barney cut a swathe through fin-de-siècle Paris as a wealthy lesbian adventurer who publicly denounced monogamy (although it was her long-time lover, the American artist Romaine Brooks, who was keener on male clothing). Her literary salon endured for 60 years, and in matters of seduction she was rarely coy: in 1899, when the young Barney took a shine to the famous French courtesan Liane de Pougy, she donned a page’s costume and presented herself at de Pougy’s house as ‘a page of love’ sent by Sappho. De Pougy’s book about their affair became a runaway bestseller.

If history is a series of reactions, one can understand today why many young women, in particular, might seek refuge in androgyny. In the first decade of this century femininity blew up into a parody of itself: the dictates of glamour began to verge on tyranny. We witnessed the expanding popularity of surgically inflated breasts, fake tans, face fillers and pumped-up pouts, hair extensions, semi-permanent eyelashes, veneered teeth and teetering heels. Little girls were showered in glitter, slicked with lip gloss and steered towards the toy section where everything was the same screaming shade of bubblegum pink. And just as some men — repelled, perhaps, by machismo — are drawn to the bright lights of this feminine theme park, some women are deciding that the surest route out of it is in a pair of brogues.

Yet if ‘gender fluidity’ was always with us, some traits of the current revolution seem more about censoriousness than freedom. In the past gender-bending was a means of defying labels; today, it more often seems like a way of acquiring them. Gender has become the chosen ground for a new wave of identity politics.

One ingredient has been the rise in organised transgender activism. As gay and lesbian organisations gained political clout and social recognition, many transgender people justifiably felt isolated: they were often ridiculed and left to navigate prejudice alone (a study last year uncovered a grim statistic: that 48 per cent of trans people under 26 had attempted suicide). It is surely right that society should treat transgender people with more courtesy: some trans women I spoke to told me that complete strangers have quizzed them on the precise nature of their genitalia.

Yet the argument about sex and gender has grown increasingly factional. On university campuses and social media it has often created not a new utopia of relaxed tolerance, but claustrophobic bickering over terminology and thought-crime. In a climate of competitive victimhood, where the key phrase is ‘check your privilege’, there is a battle over who can claim the highest level of oppression.

The claim to being woefully misunderstood has a particular allure for clever young female students. One such, Farhana Khan, wrote recently in the Independent about her ‘pansexuality’. At the end of the article, she noted that she had exclusively dated men. It was outrageous that some people used this to cast doubt on her pansexuality, she said, since ‘I’m attracted to all different kinds of people.’ It appeared to me as if Ms Khan was pansexual in the same way that I am a resident of Ulan Bator, on the basis that I haven’t actually visited but might like to go there some day. Then again, such an interpretation marks me as out of date: identity is no longer about what you actually do, but the hazier notion of how you might feel.

Transgender activists and their supporters use the prefix ‘cis’ to describe those who identify as the sex they were born into, speaking of ‘cis privilege’. Some radical feminists, however, resent ‘cis’, and counter that trans women were born with male privilege. When Germaine Greer spoke at the Cambridge Union earlier this year, she reportedly said with her usual bluntness that trans women do not know what it is to have ‘a big fat hairy smelly vagina’, and argued against the ‘unethical’ use of surgery in transitioning. A boycott of Greer’s talk was organised by Em Travis, a first-year Cambridge student, who condemned the decision to invite the ‘unapologetic transmisogynist Germaine Greer’.

Travis describes herself as ‘non-binary trans’ although ‘mostly coded as “appearing female”’. In other words, she looks feminine — acutely so, from pictures — but doesn’t ‘identify’ as either gender. That’s tough, Travis says, since ‘all too often, we are forgotten or erased, either by the world at large or by the queer community itself’.

Big deal, one is tempted to respond. For who indeed does feel or behave wholly like a man or a woman, when characteristics are often defined by stereotypes in any case? Must George, the headstrong, crop-haired heroine of Enid Blyton’s The Famous Five, now be specially categorised as ‘non-binary trans’? I myself am fond of heels and make-up, but am also untidy, poor at multitasking, and keen on Antony Beevor’s military histories. I have a shed in the garden, and sometimes my husband amuses himself by comparing me to Mark Corrigan, the misfit bachelor from Peep Show. Maybe I am internally ‘non-binary trans’ too, but then — by the lights of not strictly conforming to a mutating set of stereotypes — so are many women I know.

Unless one’s biology and identity feel so wildly out of whack that it causes severe, continuing unhappiness, mightn’t it be best — while choosing whatever clothes and relationships bring you joy — to quit the more nebulous refinements of self-definition and get on with life? Or, perhaps, to concentrate those campaigning energies on situations in which people face truly horrifying persecution for perceived departures from heterosexuality? In Isis-held Syria, for example, or Putin’s Russia. Instead, to paraphrase Allen Ginsberg, I see the best minds of their generation destroyed by jargon.

Gender-blurring has hit the Tinder generation: in terms of sexual choice, a ‘swipe right’ market of wild capitalism has replaced the old Soviet-style system in which demand reliably outstripped supply. Yet many students now seem as obsessively preoccupied with finely categorising their sexual and gender identities as their grandparents once were with stamp collections. Still, it will probably put a brake on youthful libidos: while it might not always be an option to laugh someone into bed, it is surely still possible to bore someone out of it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in