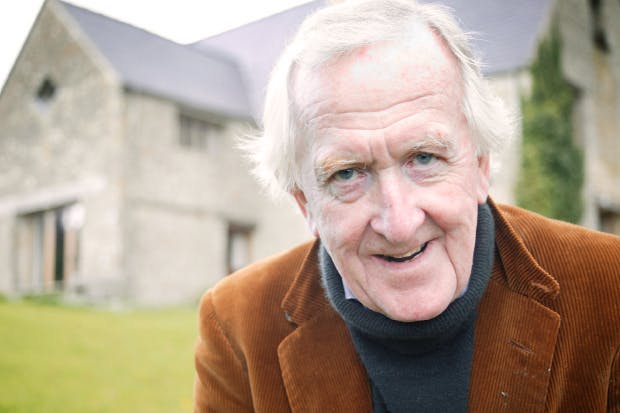

‘Elms at the end of twilight are very interesting,’ wrote Gerard Manley Hopkins in his journal: ‘Against the sky they make crisp scattered pinches of soot.’ P.J. Kavanagh, who has died aged 84, plucked out this observation for one of the columns that he wrote for The Spectator between 1983 and 1996.

He was right to call a volume collecting these Life and Letters columns (with a later series from the TLS) by the name A Kind of Journal, for they possess the kind of narrative impetus that makes classic diaries such as Woodforde’s or Kilvert’s so compelling. But they were also a poet’s work-books, just as living in rural Gloucestershire, as he had since 1963, was to be in a poet’s workshop.

For, despite the success in 1966 of his classic memoir The Perfect Stranger (which set the death of his first wife, Sally, aged 24, as the abiding marker for the rest of his life), Patrick Joseph Kavanagh was before anything a poet. His New Selected Poems came out only last year. The Spectator was also lucky enough to have him as its poetry editor, at a time when some other periodicals were beginning to lack the courage to publish poetry, despite its popularity.

He was not a nature poet exactly. He was sharply aware of the dangers of mere dabbling in rural life, quoting Peter Reading’s lines: ‘Phoney-rustic bards,/ Spare us your thoughts about birds.’ But he settled in a converted barn with his wife Kate and their two boys, earning his living by writing, after spending the 1960s in acting. He was no shrinking violet, and had thriven as a presenter, with David Frost and William Rushton, of the satirical Not So Much a Programme More a Way of Life. His father had, after all, been the writer of ITMA. But the main thing was to persevere in his task of seeing things. ‘If description is revelation,’ Derek Mahon said of his poems, ‘his revelatory gift is prodigious.’ Description can be, as he showed.

It seemed that the more sharply he saw and the more sparely he described things, the greater the burden of transcendence his poetry could bear. He was struck by something the painter Wogan Philipps (Sally’s father) had said. ‘We were looking at the hills where he had farmed, and which he had painted in semi-abstract oils often and well,’ Kavanagh recalled. ‘Suddenly, he said, as though I had indeed spoken, “I want to see what’s underneath those hills”.’

Perhaps that was one reason that Kavanagh admired G. K. Chesterton (who does not always benefit from his admirers) and published a selection of his writing. Chesterton felt that we see only the back of the world, and he yearned to get round and see it proper-side round.

Kavanagh’s approach was not, like Chesterton, by paradox but by pared-down description. In a poem called ‘Dawn’ he wrote of a mosaic in Ravenna: ‘Such rigour, dawn-simplicity, knocks you flat.’

There was, he knew, ‘something about’ in the world that it would be ‘treason to deny’. It was ‘not something religious, that is a slippery word. Or spiritual. There is joy or hope. I think it’s joy.’ The joy came from something gratuitous. ‘The world was infinitely better than it could be,’ says a character in his novel People and Weather, ‘There could have been no birds or they could all have been the same size and colour, as in nightmares.’

If this was all a gift, who was the giftgiver? P.J. Kavanagh did not write much about God, or perhaps that was all that he did write about.

The post Remembering P.J. Kavanagh appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in