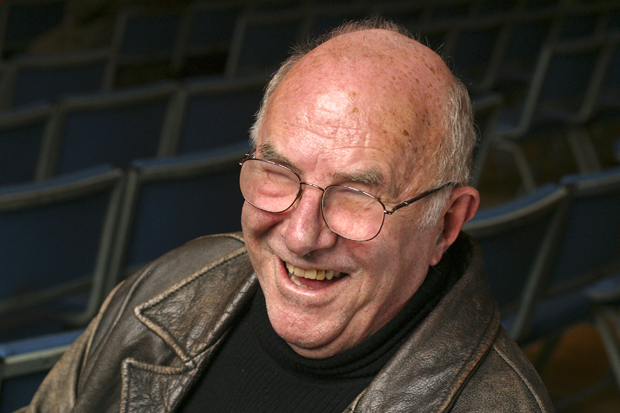

An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Education is Tony Little’s valedictory meditation on his profession, published on his retirement as headmaster of Eton. In a series of loosely connected essays, erudite and eccentric, he contemplates issues of fundamental concern to us all. What are schools for? How should teachers be educated? How do good schools work?

The book is rather oddly larded with insights from The Schoolmaster (1902) by A.C. Benson (brother of E.F. and Robert Hugh) who was, like Little, an Old Etonian who went back to teach at the school. Benson’s commentary on his own teaching experience is used as a touchstone, generally reinforcing Little’s civilising, rational approach to education.

These essays reveal Little’s vigorous moral vision. He believes in character and discipline, in agreeing boundaries and in giving boys a second chance, but possibly not a third.

He is interested in character education but acknowledges that this is a difficult issue for many schools. Eton has the advantage of time (its teachers are less constrained by bureaucracy than those in the state sector), resources and tradition. Crucially, it has teachers who ‘get it’, and it also has a thicket of traditions to underpin character education. ‘It becomes a virtuous circle: when a school has the confidence born of experience to give time and resources to character education, the more confidence it breeds in teachers.’

Young people grow to be part of the tribe at school, ‘learning where the parameters of behaviour lie, learning to accept and value discipline’. Society needs individuals with imagination and energy ‘but just as importantly it needs individuals to exercise restraint. Curbing personal dreams for a greater good is a defining mark of civilisation.’

Eton works, Tony Little says, because its pupils believe in the school and in its ways of doing things. ‘The truth is that the school operates well (indeed operates at all) because at root the pupils want it to work.’ He returns several times to this crucial insight.

The most illuminating — and idiosyncratic — section of Little’s book is his essay on adolescence. He uses neurobiology to explain why, precisely, teenage boys’ brains go haywire. The headmaster admits that he now realises that a carpeted pupil who replies to the question ‘Why did you do it?’ with ‘I don’t know, sir’ is telling the truth. Little’s sympathetic study of the adolescent brain is leavened with bracing common sense. He feels that we underestimate teenagers nowadays, pointing to the effectiveness of young naval officers in the age of sail as evidence that teenagers can assume considerable responsibility.

An essay on imagination stresses that this is the crucial element that will make young people effective in a globalised market place. The fashionable STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) subjects ‘can be taken to a new dimension by imagination expressed through the creative arts. Stem becomes STEAM’. Pupils need to learn to discriminate if they are to navigate a world in which many professional tasks (dispensing legal advice, diagnosing disease) can be done by a machine. They need to be able to take new knowledge and use it in a different way. They need to be able to imagine.

Little’s book is self-evidently the product of a life spent in an intensely privileged environment, where preposterous traditions can become powerful opportunities for discussion of values that are crucial to civilised behaviour.

There is much in this Intelligent Person’s Guide, however, that is relevant to anyone involved in the struggle to educate young people and in particular to anyone trying to reform a school that has gone badly astray. In one of the later essays, ‘Turning it Around’, Little observes the successes of struggling heads of grim state schools. He describes the transformation of an establishment in Slough that was staffed by unambitious and complacent teachers who were utterly unconcerned by the arrival of their third new head in three years. They were confident that ‘local difficulties would be resolved, an objectionable, demanding new head would be seen off and life would continue as before.’ Within a year Little witnessed the new head’s success. He found the school calm and ordered with a sense of momentum and direction:

A high-performing school can by sustained by institutional momentum for a while. Heads in the business of turning around a school have no such luxury. They must necessarily concentrate on getting the basics right day by day — and that requires a deep well of energy from which to draw.

The chapter on spirituality is the least interesting element of this book. The author is good at morals, but religion at Eton, it would appear, is mostly sunbeams on ancient stone.

Nevertheless, this is a wonderful book. Tony Little captures the magic, the surprising alchemy that makes things work in an outstanding school, and offers hope and inspiration to people elsewhere who are battling lethargy and low standards.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £14.99 Tel: 08430 600033. Carey Schofield was until recently head of Langlands School and College in Chitral, Pakistan.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in