It has often been related how, towards the end of his long life, a critical barb got under J.M.W. Turner’s skin. ‘Soapsuds and whitewash!’ Turner apparently snorted, repeatedly, to himself. However, until now no one has traced the perpetrator of this memorably tart comment.

Now we know. It was the scandalous, super-rich patron and novelist William Beckford, who made it in 1831 while taking a visitor on a tour of his collection. They paused in front of a watercolour of Fonthill Abbey, Beckford’s erstwhile house — and folly — that Turner had painted some three decades earlier. The guest remarked that the painter did not paint like that these days. ‘Oh!’, exclaimed Beckford. ‘Gracious God! No! He paints now as if his brains and imagination were mixed upon his palette with soapsuds and lather.’

This is just one of the revelations in Turner’s Wessex — Architecture and Ambition, a delightful exhibition at the Salisbury Museum, whose catalogue, by the curator, Ian Warrell, contains much fresh scholarship. Most of the exhibits come from Turner’s early years — when he was working in an idiom of sharp-focused topographical accuracy that nobody could ever compare to shaving foam. At the heart of the show are two groups of paintings that the artist produced while still in his twenties for a pair of patrons with houses not far from Salisbury: Beckford at Fonthill and Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead.

The two watercolour sets Turner painted for Hoare — of Salisbury Cathedral and city — are enjoyable partly because of their architectural precision. When you step outside the museum, you can see several of the subjects of the pictures — and note how some, such as ‘Gateway to the Close’ (1796), have changed little in more than 200 years.

Warrell suggests that one of the reasons why Hoare, a keen antiquarian, had commissioned the pictures was that the cathedral had already been drastically altered from its medieval appearance by the architect James Wyatt. Even more sweeping changes were mooted — supported by the reckless, vulgar and visionary Beckford and opposed by the more conservative Hoare.

In these pictures, you can see the youthful Turner balancing this careful accuracy with something quite different: a sense of the sublime. When painting the ‘Chapter-House’ (1801), for example, he shrank the children playing near the central pillar to a Lilliputian scale, thus making the light-filled space even more vast and numinous than it actually is.

Similarly, he presented the 300-foot tower of Fonthill — a house like a dream from Gothic fiction — from a distance, looming over wooded landscape. The lack of close-up studies of the building was perhaps a tactful evasion of the fact that the structure collapsed intermittently even as it was being built.

Fonthill was a metaphor in masonry and mortar for Beckford’s soaring imagination and, in literal fact, lack of firm foundations. This incomparably impractical structure fell down finally and catastrophically in 1825 — shortly after Beckford had succeeded in selling it, but not before he had spent much of one of the largest fortunes in Europe on the project.

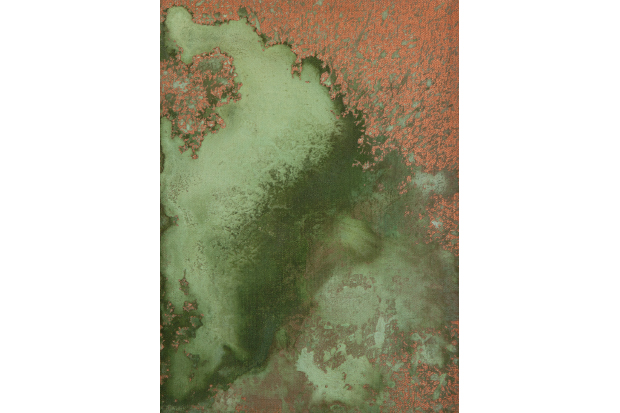

Turner’s own imagination had left topography far behind by the end of his career. The unfinished, ‘Arrival of Louis-Philippe’ (c. 1844–5), a highlight of the exhibition, is exactly the kind of picture Beckford had in mind when he made his rude observation, although really it is sun, sea and moist air it evokes rather than washing-up.

To Turner’s great opposite, equal and fellow painter of Salisbury John Constable, landscapes had a soundtrack. We know from a famous letter that Constable wrote to his friend Archdeacon Fisher that it was not only riverside sights such as slimy posts and rotten planks that he loved but also ‘the sound of water escaping from mill dams’.

Can one take that insight a stage further and exhibit paintings with associated noises? This is a question boldly posed by Soundscapes at the National Gallery, which presents six pictures from the collection with musical and other aural accompaniment.

The short answer turns out to be ‘no’. It is a qualified negative, however. The three musical scores are simply distracting. The others are more thought-provoking. Susan Philipsz is the exponent of ‘sound art’ who has come closest to convincing me there is such a thing. Her ‘Air on a Broken String’ is quite an interesting experience in which violin notes emerge from three speakers, mingling in space. It’s just that I’d rather not hear it in front of Holbein’s ‘The Ambassadors’. But best are the natural sounds such as birdsong that the wildlife recording specialist Chris Watson supplies as an adjunct to the Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s picture of ‘Lake Keitele’ (1905). Still, the lesson seems to be that the soundtracks to paintings are best left inside the artist’s head.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in