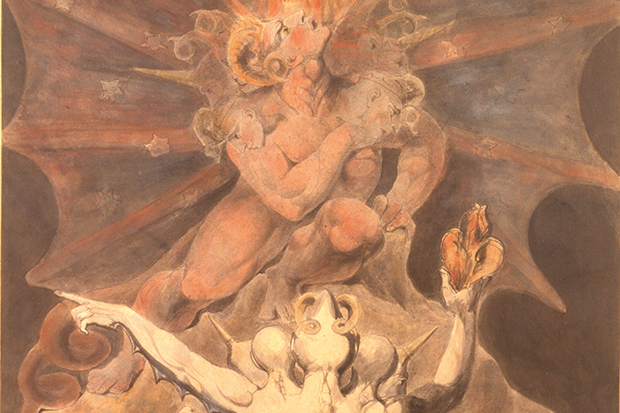

At the heart of the eschatological ideology of the Islamic State is the belief that when the world ends (and the world ending is a good thing in their estimation) the final conflagration will take place in northern Syria, in an unremarkable town called Dabiq (which Isis presently occupy). It is here that the Armies of Rome will combine forces against the Armies of Islam, and the Armies of Rome will be defeated.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.50 Tel: 08430 600033Nicola Barker’s novels include Wide Open, the Man Booker-shortlisted Darkmans and, most recently, In the Approaches.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in