When Margaret Thatcher imagined perfect power, she thought of the orchestral conductor. ‘She envied me,’ said Herbert von Karajan, ‘that people always did what I requested.’ Power, however, is a mirage that fades as you get close. What Mrs Thatcher saw were the trappings, never the essence. Great conductors might get the glory, but someone else pulled the strings. Behind every power there is a greater force. Behind every conductor, there was Ronald Wilford.

It is hard to think of Wilford, who died last week, aged 87, without a sneaking admiration. A self-schooled Machiavellian, a Mandelson of music, he invented a chimera of ‘the great conductor’ and, as president of Columbia Artists (CAMI), sold it at unimaginable profit.

Peak price for a Wilford conductor at a major US orchestra was $3 million for 14 weeks work. His maestros, holding jobs on three continents, became obscenely rich and far removed from the musicians who did their bidding. The conductor was the banker, the rest were mugs. The paradox is that by making conductors appear omnipotent, Wilford fatally weakened the species, leaving it, at his death, almost impotent.

Every major player in classical music had an attitude to Ronald Wilford. One night, he strayed into conductor Lorin Maazel’s green room, oozing post-concert blandishments. Lorin grabbed him by the throat, slammed him against a wall (so he told me) and growled into his ear, ‘Before I’m done, Wilford, I’m gonna buy out your business and throw you on to the street.’

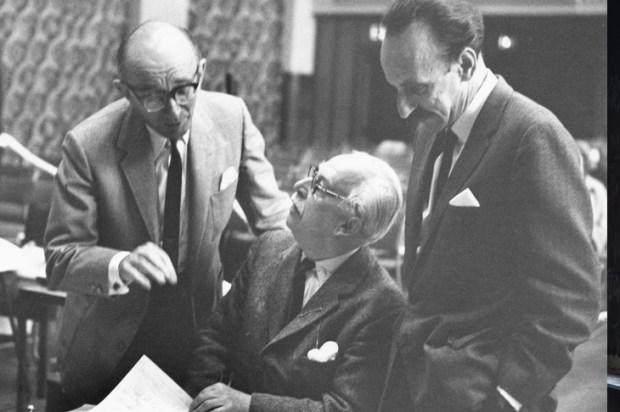

Sir Colin Davis, by contrast, so revered Wilford that after reading the chapter I wrote about him in The Maestro Myth, he never spoke to me again. Wilford had raised Davis from English obscurity to a well-paid position in Munich. He put Riccardo Muti into Philadelphia, Neville Marriner into Minnesota, Seiji Ozawa into Boston. André Previn, a Hollywood pianist, he ran up through boondocks orchestras and signed to the LSO. He controlled the careers of 111 music directors. No fewer than 100 signed his 60th birthday card.

James Levine was his trump card. Jim was a Cincinnati kid who, from the age of 28, Wilford groomed to become chief conductor of the Metropolitan Opera. With Levine inside, Wilford had fast-track entry to America’s wealthiest opera house. The Met’s present general manager, Peter Gelb, is Wilford’s former trainee. The Met director who gave Levine his job was rewarded with a directorship in Wilford’s business.

A slim man, married to a Roosevelt and expensively suited, Wilford generated shock and awe. Managers at Vienna’s Imperial Hotel, opposite the Musikverein, would jump to attention. ‘If you were a young artistic administrator you did not say “No” to Ronald Wilford,’ a US orchestra president told me last week. ‘If you did, it was curtains for you.’

Wilford’s 57th Street office, opposite Carnegie Hall, was a Japanese shrine, shards of light filtering through Italian blinds. When I interviewed him (the second, and just about the last, he ever gave), Ronald sat in Zen gloom, motionless as a Buddha. Although he saw me taping the interview, he later denied it had ever taken place.

His origins were mixed and muted. Son of a Greek father and a Mormon mother in Salt Lake City, he fled to New York and began hanging around the CAMI offices, babysitting for junior secretaries to get a foot in the door. CAMI belonged to Arthur Judson, a founder of the CBS network and ex-manager of the New York Philharmonic. Wilford, reviving a moribund theatre division, toured the French mime Marcel Marceau to enormous profit and hauled Otto Klemperer out of penniless depression.

In 1961, he grabbed the conductor’s division. More clinically than any agent before or since, Wilford understood that conductors were the key to power. He who had the most conductors on his books could stack the season with his artists. Wilford built CAMI into a warehouse of 800 classical artists and made the orchestral sector dance to his tune. Where Judson helped new US orchestras to find their feet, Wilford slammed them with ever-rising fees. ‘He gave every artist his full attention,’ says a CAMI flack, ‘until he was finished with them, and then they were dead.’

Like Margaret Thatcher, he worshipped Herbert von Karajan. Half-Greek on his father’s side, Karajan bonded with Wilford and used him to develop the Berlin Philharmonic brand in Asia and the US. Each exploited the other businesswise, but there was more to it on Wilford’s side. ‘He was in love with Karajan,’ says a close friend. ‘Every lunch we had, the talk would always get round to Karajan.’

Missing out on the younger generations, the Rattle-Salonens and the Dudamel-Nelsons, Wilford saw his power fall apart. Nowadays it is musicians who pick the music director, not Wilford. Mega-agencies have gone phut. ICM quit music. CAMI vacated 57th Street. Wilford kept working to the week of his death. The last appointment he negotiated was Daniele Gatti’s at the Concertgebouw. If he left a legacy it is in the scale of conductors’ wages: no good part-time job changes hands for less than a million dollars.

Painfully shy, he would probably prefer to be forgotten. But Ronald Wilford energised the classical music scene in his time and made it seem, somehow, larger than it objectively is.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in