‘I had had a fantasy for years about owning a dairy farm,’ says Mary Norris, as she considers her career options in the first section of this odd but charming cross between a memoir and a usage guide. ‘I liked cows: they led a placid yet productive life.’

Instead, she found a productive life — if not always as placid as she might have liked — as a copy editor on the New Yorker magazine. In Between You and Me, she presents the accumulated wisdom and winsome anecdotes of several decades of proof-reading, editorial queries and office arguments, ‘for all of you who want to feel better about your grammar’.

New Yorker memoirs are a genre of their own — no other publication generates such stylish mythology, in such bulk — but Mary Norris has something distinctive to add: a layer of clerical intrigue beneath the famous writers and distinguished editors. There are the gentle eccentrics of the collating and foundry departments. There is the pencil boy, ‘who came around in the morning with a tray of freshly sharpened wooden pencils. And they were nice long ones — no stubs.’ (Not even the New Yorker has a pencil boy any more; nor, I suspect, foundry and collating departments.) Above all, there are two women, Eleanor Gould and Lu Burke.

Gould, a house pedant of bewildering exactitude, has had press before, although Norris adds some excellent stories about her (‘My all-time favourite Eleanor Gould query was on Christmas gifts for children: the writer had repeated the old saw that every Raggedy Ann doll has “I love you” written on her little wooden heart, and Eleanor wrote in the margin that it did not, and she knew, because as a child she had performed open-heart surgery on her rag doll and seen with her own eyes that nothing was written on the heart’).

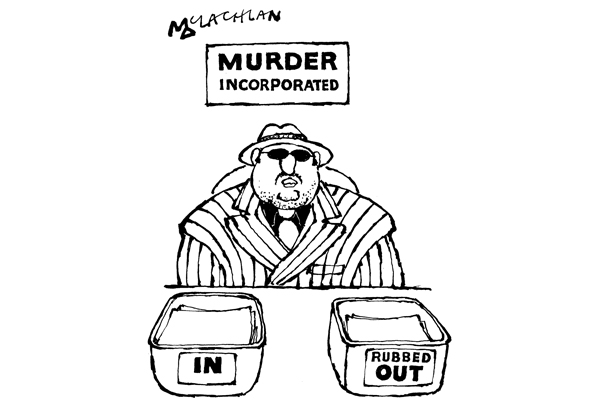

Burke is a less exalted senior colleague who seems to have been both a mentor and a warning for Norris. She serves Between You and Me as an exemplar of a less fussy editing style than Gould’s and as a bad-tempered balance to Norris’s niceness: she was the kind of copy editor who throws tantrums in corridors, belittles newcomers who dare to question her hyphen placement, and conducts quixotic campaigns against house style. She kept a tin labelled ‘comma shaker’ on her desk as a protest against all the punctuation she had to insert. She fought the New Yorker diaeresis — the chichi umlaut lookalike with which the magazine reminds its readers how to pronounce coöperate and reëlect — by repeatedly badgering the elderly style editor: apparently he agreed to surrender after she cornered him in the lift, but then died before he could send out the memo.

Norris, by contrast, believes in sweetness, light, and commas. She is so protective of the Oxford comma — the one before ‘and’ at the end of a list: see previous sentence — that she considers it a patriotic affront to name it after an English city. (She repeats the old claim that removing it creates ambiguity. Sometimes it does, as in the internet example she gives: ‘We invited the strippers, JFK and Stalin.’ But including the comma can create ambiguity, too: ‘My wife, a fluffy bitch called Fifi, and I were walking along the beach.’) Her grammar rules in general vary from standard-issue prescriptive (‘they’ as alternative to ‘he or she’ is ‘just wrong’) to the New Yorkerishly baroque (a dash may not follow a colon in a sentence; no sentence should contain more than one colon).

What makes her instructive as well as amusing is her willingness to make exceptions, and her vivid, sensitive explanations of particular exceptions she’s made. One confession tinged with genuine guilt concerns a dangling modifier she now feels she should have permitted to dangle. Even singular ‘they’ is let stand if the alternative is to spoil a joke. If she can encourage fellow copy editors (I am one) to ‘feel better about grammar’ by using it as a means to concentrate on meaning and nuance with a similar level of sympathetic attention, then her book will do writers — and readers — a service.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £13.99, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in