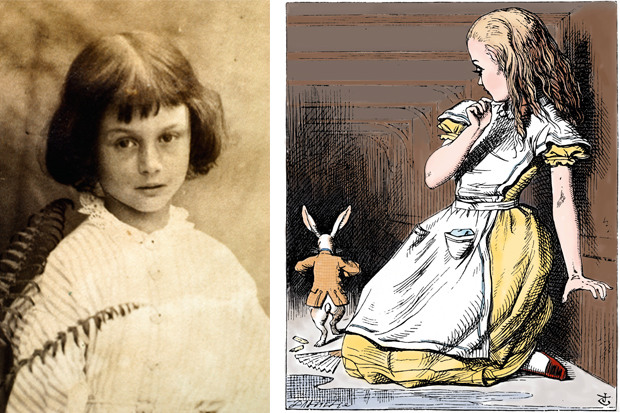

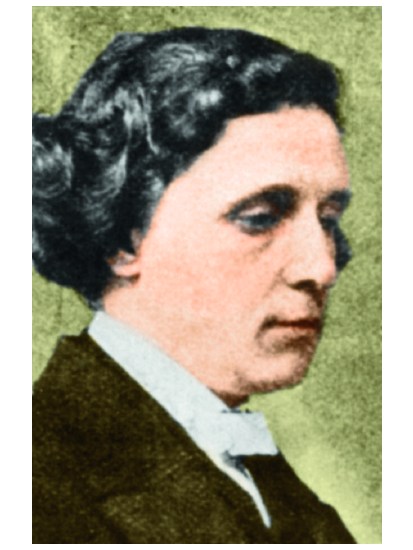

‘A vision of innocence was not always the same as an innocent vision,’ remarks Robert Douglas-Fairhurst. He is referring to Alice’s discovery in Wonderland that ‘ “I say what I mean” is not the same as “I mean what I say”.’ Douglas-Fairhurst is a subtle expert in doubleness. His new book tells the story of Lewis Carroll, who was also an Oxford mathematician called Charles Dodgson, and Alice Liddell, whom Dodgson photographed naked when she was seven, who married and became Mrs Hargreaves though she liked to use the title Lady Hargreaves, to which she was not entitled.

In 1862 Dodgson took Alice and her siblings on a boat trip on the river from Oxford to Godstow, during which he told the story of Alice’s descent to a world underground, inhabited by fantastic people and creatures. Alice asked him to write it down. It was published in 1865, with illustrations by John Tenniel, and a sequel, Through the Looking-Glass in 1871. The story gripped both their lives.

Lewis Carroll, like many other Victorian ‘innocents’, was obsessed by the beauty and incorruptibility of young girls. The camera was a fairly recent invention. He used it to make images of girls dressed as princesses or beggars or — the clearest image of innocence — naked. Douglas-Fairhurst has fun — while making a serious point — with Carroll’s involuted letters to Alice’s mother (and other mothers) seeking permission to photograph their daughters. ‘On each occasion the correspondence turned into an elaborate dance of questions about how far they might go towards “absolute undress”.’ Douglas-Fairhurst shows that as Carroll insisted on the child’s ‘blissful unselfconsciousness’ his own writing became more selfconscious. Girls were variously ‘undraped’ or ‘undressed’; they were ‘in primitive costume’ or ‘Eve’s original dress’ or ‘their favourite dress of “nothing”.’ Douglas-Fairhurst remarks that Carroll’s increasingly elaborate attempts to avoid saying what he meant were ‘the rhetorical equivalent of a hand-tailored suit with a fancy waistcoat’.

The book goes into both innocent examples of this love of little girls and an exploration of the dark alternatives to innocence. Douglas-Fairhurst points out that the looking glass makes everything double and reverses things. Innocence first. He quotes a poem by F.T. Palgrave, a fellow of Exeter College, Oxford, later professor of poetry and editor of The Golden Treasury — an anthology with which I was familiar when I was Alice’s age. Palgrave wrote a poem, ‘The Age of Innocence’, which is — to put it simply — extremely embarrassing. It is addressed to:

The little wonderer at my knee—

Is she the Vision robed in light—

The Fairy Fair — the gracious sight;

The angel child that loosed the chain…?

After there has been an embrace, the poem concludes:

The white soft frock — the sash of blue —

The edging lace — the tiny shoe —

The sock turn’d down — the ancle fine—

The wavy folds — the bosom line.

The kiss is described in detail:

The quick warm breath: the heaving breast:

The tender weight against me prest:

The fair fine limbs — the soft — the pure —

All maidenhood in miniature.

Douglas-Fairhurst offers some equally touching or horrifying descriptions of male passion for innocent and delectable child-friends. He has a passage identifying these persons — people too young to inhabit the world of sex and marriage, yet offering what? A kiss seems to be the ultimate delight of this world. Carroll the mathematician wrote to one girl: ‘I send you 1,0000000 kisses’, and to another: ‘I send you 4 3/4 kisses; please give ½ of a kiss to Nellie and 1/200 of a kiss to Emsie, and 1/20000000 of a kiss to yourself.’

This is ponderous and jokey enough. But Douglas-Fairhurst reminds us of the work of W.T. Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, who in 1885 conducted secret search into a concealed network of brothels and locked rooms that stretched out across London, where young virgins were ‘served up as dainty morsels to minister to the passions of the rich’. Stead quotes a brothel-keeper who assured him that ‘as the walls are thick’ and there was ‘a double carpet on the floor’ any girl he chose ‘may scream blue murder, but not a sound will be heard’.

Carroll’s manoeuvres were awkward on the edge of innocence. In 1880 he mistakenly kissed the daughter of one of his Christ Church colleagues who turned out to be 17 years old. His amusing ‘apology’ to her mother was ill-received, and not long after that he gave up taking photographs. His extraordinary innocence or deliberate blindness is shown in a story about his attempt to buy a copy of a civil war painting by Thomas Heaphy called ‘General Fairfax and his Daughter pursued by the Royalist Trooper’. He wanted only the child in the painting. All he remembered, it seems, was ‘the fainting child’ — and the title he eventually chose for his copy was ‘Dreaming of Fairyland’!

In later years he seems to have spent his summers on the beach at Eastbourne, accompanied by a series of child-friends. There was ice-cream and paddling and affection. I love the story of the 11-year- old Nellie da Silva in 1876. She decided that the bathing-machine man was ill-treating his horse. So she fed his lunch to the horse and set about smashing the glass in the peepholes of the bathing machines. We’re not told what happened next. But the incident shows Douglas-Fairhurst’s precision and liveliness as a narrator. He is constantly surprising and often shocking, quietly and carefully.

I have concentrated on the doubleness and single-mindedness of Dodgson/Carroll. But The Story of Alice is splendidly interesting about the world in which the Alice books were written, and the way in which Carroll tried to keep hold of his child-friends and freeze them — so to speak — at a certain age. It is also interesting about Mrs Hargreaves, and her journey to New York, aged 80, where she was besieged by journalists curious about the famous Alice.

Douglas-Fairhurst is a startling and exciting writer. I shall not forget his description of the Alice books — compared to Carroll’s last novel Sylvie and Bruno — as being ‘as slim as snakes’. I had to make an effort to remember myself as a reader, about Alice’s age, being startled and delighted on every page of those books, but completely unaware of little girls and loving men, ambivalence and meaningfulness.

They are eventually books for solitary, surprised children. How did that man do that? This book helps us to see, even while unravelling our innocence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033. A.S. Byatt is a novelist and poet. Her books include The Children’s Book, Still Life and the Booker Prize-winning Possession.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in