John Hemming is our greatest living scholar-explorer. He is best known for his extraordinary first book The Conquest of the Incas, published in 1970 when he was 35 — a work of vivid, monumental scholarship that is still unsurpassed. His love for the peoples of the Amazon produced a remarkable historical trilogy: Red Gold (1978), Amazon Frontier (1987) and Die If You Must (2004), which together cover the years from 1560 to the end of the 20th century. They are big, magisterial, powerful works, perhaps driven by one intense memory…

In 1961 with his friends from Oxford, Richard Mason and Kit Lambert, he mounted an expedition to map the course of the Iriri river. All went well for five months until tragedy struck, as Hemming writes in Die If You Must:

Richard Mason’s body was found, lying on the main supply trail a few kilometres from our camp. He was carrying a load (mostly sugar) up from Cachimbo and had walked into an Indian ambush. He had been hit by eight arrows, and his skull and thigh were smashed by club blows. Some 40 arrows and 17 heavy clubs were arranged around the body.

In 1996 Hemming visited the tribe that killed Mason, now known as the Panará. They had had no knowledge of clothes and the swish-swish of Mason’s jeans as he walked had unnerved them. Typical of Hemming, he had left a present of machetes at the place of death — which he found the Panará still possessed and valued (they’d had no metal tools).

After a lifetime spent travelling in the Amazons and documenting their tragic histories it is perhaps inevitable that Hemming should turn to three stories of earthly delights around the great rivers: the biographies of a group of immensely attractive young English naturalists. Not history or politics or war or conquest but natural history, which never lets you down. Hemming’s title is apt: Russell Wallace, Henry Walter Bates and Richard Spruce were indeed naturalists in paradise.

But they were different to the norm. You could call them working-class naturalists, in that they had to pay their way by sending the specimens they captured home to their agent, to be sold to wealthy collectors. A comforting branch of English Protestantism known as natural theology had by that time become mainstream (the standard text being Archdeacon Paley’s Natural Theology, 1802). This belief that God had made everything himself (that no minor woodlouse or tiny liverwort was too small for his loving creation) led to the great aristocratic collections of the 19th century. The idea was to buy in specimens from a worker in the field — a Wallace or a Bates or a Spruce — arrange them in a mahogany cabinet, pull out the drawers, study, and thereby get to know the workings of the hand of God. This was ironic, because not one of this trio was a believer. As Wallace wrote to Bates, when they arrived in the Amazons they would study the facts of nature and work ‘towards solving the problem of the origin of species’. Which they did, eventually.

But first, here is Hemming’s characteristically delightful description of Wallace and Bates in Belém in Brazil, the gateway to the Amazon:

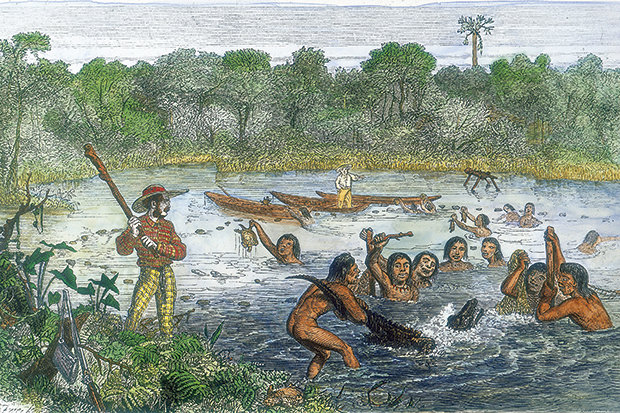

They happily settled down to three months of professional collecting in their fine rented house. It had forest on three sides, with overgrown trails. They were delighted to learn that one of these led to a house used 30 years earlier by the Bavarians Spix and Martius — the first foreign naturalists allowed on the Amazon. Another road led east, but was now so overgrown as to be almost impassable. Their routine was to rise at dawn, to a cup of coffee made by their servant Isidoro. He would then go to the town for the day’s provisions, and the collectors spent two hours on ornithology — trapping or shooting birds. At about ten o’clock, after breakfast prepared by Isidoro, they spent four or five hours on entomology, since the best time for insects was before the midday heat. They were fortunate that one of the three men who tended their house’s trees and garden was celebrated as a catcher of insects, reptiles and small mammals.

This was Vincente,‘a fine stout handsome black man’. In the evenings the three young men prepared their specimens and took notes. As we see here, they had already invented a new kind of travel-writing, books in which their guides and helpers were given full credit and brought to life.

All three naturalists were obsessed, driven and remained utterly fascinated by their surroundings. Their stories of the Amazons are full of adventures, difficulties to overcome and disasters. But what of their achievements? Apart from the massive collections themselves (Bates, for one, brought home 8,000 new species), Spruce stole the seeds of the cinchona tree from Ecuador and so gave the British empire quinine, the only known defence against malaria. Bates gave his name to Batesian mimicry, discovering how various edible species — unrelated moths and butterflies, for instance — had evolved to show ‘a perfectly staggering likeness’ to a poisonous species in order to deter predators. Wallace began to accumulate the vast experience that eventually led him, in 1858, to write to Darwin with a full account of the theory of evolution by natural selection.

I have read every individual biography of these three men, but Naturalists in Paradise is by far the best history of their lives in the Amazons. Hemming turns the technical nightmare of combined biographies into a seamless daydream — perhaps because he knows the country they explored so very well himself. His book is itself a little piece of intellectual paradise.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.95 Tel: 08430 600033. Redmond O’Hanlon’s books include Congo Journey, In Trouble Again and Into the Heart of Borneo.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in