This is not quite another story about a man who never was. But it is about a man who certainly wasn’t what he said he was.

The context is Russian intelligence operations of the 1930s, especially those of the NKVD (known later as the KGB) during the Spanish civil war. In Britain we tend to see 1930s/1940s espionage through the prism of the Cambridge spies — Philby, Burgess, Maclean, Cairncross and Blunt, the so-called Ring of Five — but, as Boris Volodarsky points out, the full picture is much wider. By 1937, he reckons, the Russians had over 100 agents and collaborators in Britain alone, with many more in other western countries. And they were ruthlessly active in Spain.

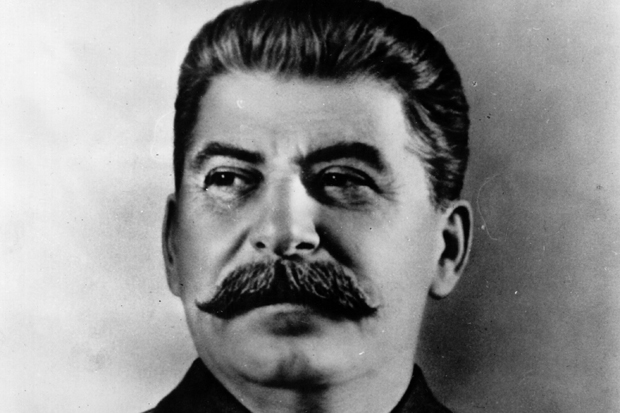

In 1938 a Russian calling himself General Alexander Orlov fled from Spain to America, where he settled, unknown to the authorities, with the modern equivalent of $1.5 million in embezzled funds. Following the death of Stalin in 1953 and the exhaustion of his funds, he sold his story to Life magazine as ‘the highest-ranking Soviet intelligence defector’. Well aware of what the Russians did to defectors, he claimed to have sent a letter to his former masters promising not to reveal any secrets so long as he was left alone, but threatening that all would be revealed if anything happened to him. He then made a fortune through articles and books, convincing the FBI and CIA of his genuineness to the extent that he was taken on as an adviser and wrote a number of official publications. He presented himself as a friend of Stalin’s and as the NKVD general in charge of operations in Spain during the civil war. Among many other achievements, he claimed to have recruited Philby, Maclean, Burgess and Blunt.

In fact, there was no NKVD General Orlov in Spain — the rank did not exist until after the second world war. The man claiming to be him was Lev Lazarevich Nikolsky, a failed NKVD officer who had served in Spain and also briefly in London and Paris. He was for a while Philby’s case officer but was not a success — in both London and Paris he pretended his cover was blown in order to be withdrawn before his failures became more apparent. He was demoted to the transport department. In 1936 his personal life became a professional embarrassment when his mistress shot herself outside the Lubyanka. He was spared further disgrace by the NKVD’s need to post someone to Madrid, whence he later fled with (genuinely) stolen funds, reinventing himself as Orlov from a tangle of truths, half-truths, lies and fantasies.

Volodarsky, himself a former officer of the GRU (Russia’s military intelligence service), has spent 13 years untangling Nikolsky’s deceptions. He adds considerably to what is known about Russian operations in the Spanish civil war, not least in emphasising how the elimination of Trotskyists was always more important to Stalin than establishing a communist regime in Spain. He also usefully illuminates the early history of the Ring of Five, stressing the crucial role of the Austrian Arnold Deutsch in recruiting them, while pointing out that they were never quite the coordinated network their title implies. Finally, he lists Russian agents, collaborators and sympathisers of the period, including Labour party and trade union spies and useful idiots or agents of influence such as Christopher Hill, the Master of Balliol who ‘saw no famine’ in the Ukraine in 1933 and who characterised Stalin’s purges as ‘non-violent’.

Overall, Volodarsky’s researches into the context of his story are as revealing and interesting as the story itself, particularly as Russian intelligence history is a subject so ridden with confusions, contradictions, fabrications and omissions that no one, then or now, knew or could know the whole truth. It is a pity that Volodarsky clearly wants to believe the claim by the fantasist and former MI5 officer Peter Wright that Roger Hollis, head of MI5, was a spy, though he stops short of endorsing it.

Russian intelligence operations are a seam of 20th-century European history that can no longer be ignored. In unearthing many nuggets of gold and showing how the KGB eventually endorsed Orlov/Nikolsky’s self-serving lies by turning them into a disinformation operation, Volodarsky enhances our understanding. His is not the last word — we’ll never get there — but it is a significant and valuable addition.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £25 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in