In a recent interview, the celebrity historian and Tudor expert David Starkey described Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall as a ‘deliberate perversion of fact’. The novel, he said, is ‘a magnificent, wonderful fiction’.

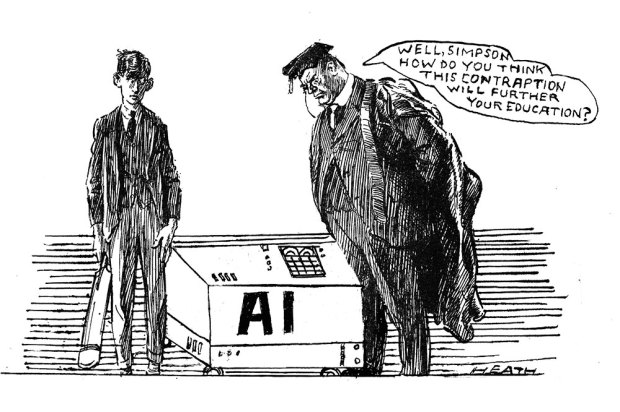

But if Oxford has taught me one thing, it’s that all the best history is. Starkey is a Cambridge man, and maybe they do things differently there. But any perceptive Oxford undergraduate will soon realise that a little bit of fiction is the surest way to a First. What the admissions material opaquely describes as ‘historical imagination’ turns out to be an irregular verb: I imagine, you pervert the facts.

Any success I’ve had in my first year and a half at Magdalen College, I owe to the fact that I have no qualms about taking this approach. My highest-marked essays include ones which argue that Martin Luther was a fraud, that Second Wave American feminists were profoundly sexist and that King Alfred the Great was a historical irrelevance.

In another essay, I said that the Counter-Reformation was a success because the Catholics were so flexible, tolerant and easy-going — I didn’t mention the Inquisition once. Saying it was ‘completely wrong, but a delight to read’, my tutor gave it a First.

The same tutor recommended Fernand Braudel’s seminal 1949 tome, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, as the greatest history book of all time — while adding, as a cheery side-note, that he was sure Braudel had made all the facts up.

The list of historians who’ve been led by their imaginations as much as their sources is distinguished. In the 1960s, John Prebble’s reconstructions of the great disasters of Scottish history were blood-soaked bestsellers. His vivid narratives brought to life first the rainy, desolate moor that staged the Battle of Culloden, then the betrayal, disease and starvation of the Highland Clearances. Prebble was described by the current chair of history at Glasgow University as the man who ‘had interested more people than anyone this century in Scottish history’. But he’s still dismissed by most academics as a glorified historical novelist.

The young Niall Ferguson was the inspiration for Irwin, the provocative history teacher in Alan Bennett’s The History Boys. He taught his pupils to make tutors sit up and take notice by arguing (to use one of Ferguson’s real-life examples) that Britain should have sat out the first world war and left the Germans to battle it out.

At the end of Bennett’s play, one of Irwin’s less able students recounts the arguments that got him through his Oxford interview: that ‘Stalin was a sweetie and Wilfred Owen was a wuss’. Lines like that would still get you into Oxford today.

And if bestselling history books are about one parts fact to two parts fiction, it’s because that’s the ratio that most historians have to work with. Starkey may consider himself to be ‘someone who actually knows what happened’ in Henry VIII’s court, but the truth is he doesn’t — no one does. If Wolf Hall had been written based on facts alone, it would be a tenth as long and even less interesting. A scrupulously honest historian has to leave gaps, or add caveats until his reader died of boredom.

There are, of course, grave historical sins. To speculate is one thing, but to deliberately lie is quite another. David Irving deserves no admiration for his manipulation of the evidence surrounding second world war: losing his libel case, he was found to have ‘for his own ideological reasons persistently and deliberately misrepresented and manipulated historical evidence’. Creatively joining the few dots of knowledge we have about the past is the historian’s craft, and it takes skill. Writing something you know to be untrue because it fits your story takes no skill, and is the point where history becomes fiction.

To return to Alan Bennett, ‘History nowadays is not a matter of conviction. It’s a performance. It’s entertainment. And if it isn’t, make it so.’ For future history students, I have just one piece of advice: put down E.H. Carr’s What is History — all you need is The History Boys.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in