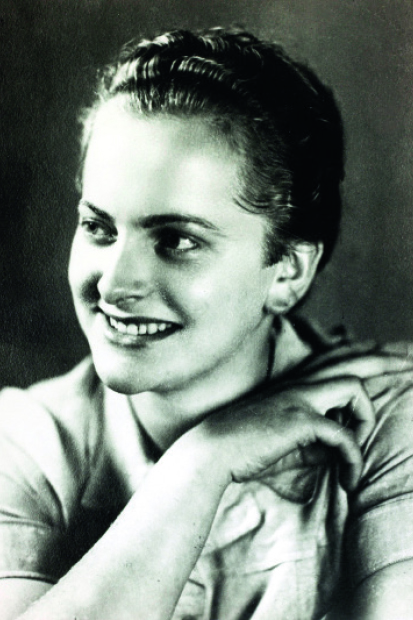

This is the tale of Muriel Lester, once famous pacifist and social reformer, and Nellie Dowell, her invisible friend. Nellie Dowell is invisible in the sense that Claire Tomalin described Nelly Ternan in The Invisible Woman. While Ternan, the mistress of Charles Dickens, simply ‘vanished into thin air’, Nellie Dowell, who may or may not have been the mistress of Muriel, trod so lightly on the ground that she left barely a footprint behind her.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £22.95 Tel: 08430 600033. Frances Wilson’s books include The Courtesan’s Revenge and The Ballad of Dorothy Wordsworth.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in