The Sykes-Picot agreement will be 100 years old next year, but there will be no congratulatory telegrams winging their way to the Middle East from London, or from Paris on high alert. The Islamic State, the world’s most powerful jihadist group, has filmed its men bulldozing border posts between Syria and Iraq, dealing perhaps the final blow to those Anglo-French cartological ambitions of a century ago.

The ‘Caliphate’ is inhabited by some six million people and is now larger than the United Kingdom. In the words of Patrick Cockburn, ‘a new and terrifying state has been born that will not easily disappear’. Yet far from appearing out of the blue in 2014, IS was fostered for years by those who profess to oppose it, as this book argues convincingly.

Cockburn takes aim above all at Saudi Arabia for promoting Islamic fundamentalism; and at Turkey, so desperate to topple President Assad of Syria that it turned a blind eye to Gulf-backed foreign fighters crossing the Turkish border.

He is right, in retrospect, that the West offered Assad impossible terms for peace, namely the president’s resignation; and that our failure, along with Russia’s, to prevent Syria’s disintegration played an even bigger role in the growth of IS than Iraq’s near collapse last year.

Iraq’s army crumbled last summer and Sunni resentment at Shia domination certainly gave IS fertile territory there. But it was Syria’s civil war which was the first conflict to go ‘viral’ online, sucking in perhaps 15,000 IS fighters, some of them now exporting their virulent jihad back to Europe.

The author argues that coalition air strikes will result in civilian casualties, boosting a fighting force which may be over 30,000 strong already. IS will probably use civilians as human shields and even if it loses territory, it could compensate by trying to take its jihad global, asserting a leadership claim over the ‘Umma’, or worldwide body of Muslim faith.

Cockburn points out that the idea of Nato air strikes in favour of ‘moderate’ rebels fighting Colonel Gaddafi in Libya was as self-deceiving as the notion of arming ‘moderates’ in Syria is now. The UK, wisely, is staying clear of Syrian rebel army building, given that support for ‘Free Syrian Army’ fighters from Gulf monarchies has comprehensively failed.

Even Iraqi Kurdistan’s fabled Peshmerga, who are now armed by Britain and others, are airily dismissed by one observer in this book as ‘pêche melba’, because young Kurdish city boys have gone so pudding soft. Yet with no surefire ally on the ground, what Cockburn would do to combat IS is not a question he really answers. So often we reporters are better at demolishing glass houses than we are at building them.

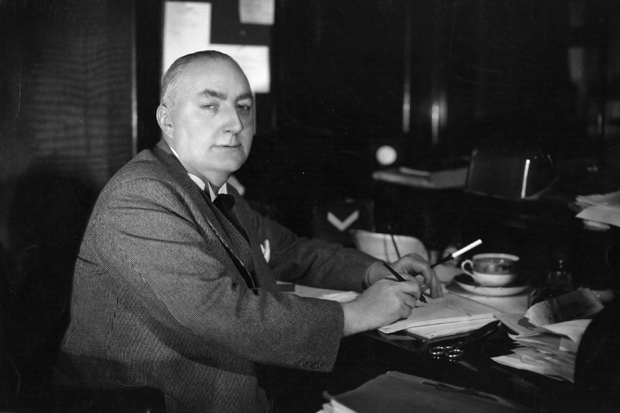

This history is so recent that perhaps inevitably it occasionally reads as rushed, though Cockburn, writing for the Independent for many years, has rightly been garlanded for spotting the emergence of IS much earlier than anyone else. He is at his best here when the sheer breadth of his experience lends huge authority to his argument. Which is that the entire ‘war on terror’ has failed since 11 September 2001 because Saudi Arabia (and Pakistan further east) were allies America didn’t want to offend. ‘Until the fall of Mosul,’ Cockburn writes, ‘nobody paid much attention.’

A more clinical history of IS and its capture of Iraq’s second city last summer is available from an ex-MI6 officer, Richard Barrett, on the website of his Soufan Group security consultancy in New York. Barrett’s essay goes further in predicting terror attacks inspired or organised by a group ‘incandescent with rage that the West will not just leave it alone to establish the utopia that it believes within its reach’.

In the positives column, there’s new political leadership in Baghdad, where the army, already in receipt of America’s billions, is once again being reformed. Prince Bandar, the Saudi intelligence chief who supplied jihadist brigades in Syria, has been sacked, though Cockburn quotes the Americans complaining that Kuwait has become the new epicentre for Syrian terrorist funding instead.

In his attempt to be balanced, Barrett reckons the Islamic State ‘may wither and die as quickly as it has emerged’. Cockburn, however, is more convincingly partisan: the disintegration of Syria and Iraq may prove irreversible.

Our best hope is that IS’s failure to govern vast swaths of both countries will eventually earn it the enmity of Sunni tribes, forcing it to morph into something less potent and toxic. Though any notion of nationhood will only reassert itself if those nominally in charge can offer their people something better.

From Afghanistan onwards, western military intervention has failed to create stability, though President Obama’s present caution speaks of his awareness of history’s terrible burden. Islamic State atrocities, including the beheading of hostages, make any talk of a negotiated peace ridiculous. And if IS is not contained, the Middle East may be at only the beginning of its bloodletting in a Sunni-Shia Thirty Years’ War.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033. Jonathan Rugman is foreign affairs correspondent for Channel 4 News.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in