On the surface Harraga is the story of two ill-matched women colliding dramatically, with life-changing consequences. What emerges, in throwaway fragments, is a picture of Algeria’s chequered past and present; a history of conquest and occupation. It’s a sugar-coated pill with a burning, bitter core.

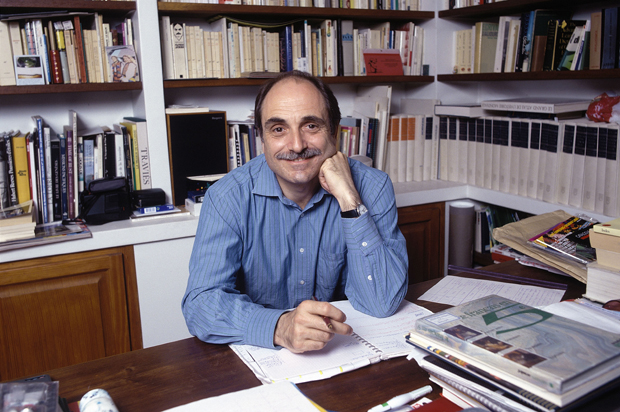

Boualem Sansal is an Algerian writer recently nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. His novels have been translated into 18 languages and won international awards. In his own country, his books are banned.

Before becoming a writer at the age of 50, he enjoyed an enviable life as general director of Algeria’s ministry of industry and restructuring, until open criticism of the regime cost him his job. He still lives in Algeria, though officially ostracised. The first of his six novels to be translated into English was the widely praised An Unfinished Business.

The Algeria of Harraga lies somewhere between nightmare and soap opera: people disappear, girls get their throats slit, neighbours pop in for a cup of sugar and a gossip. Lamia, a 35-year old paediatrician, lives alone in the ramshackle mansion that was her family home. She sees the country ‘torn between rabid reactionism and ghastly futurism’ and has withdrawn, a recluse with only ghosts for company. The house itself is a character in the story; its walls hold history. Every room offers a tale of past occupants — Ottoman, French, Muslim, Jewish.

Choosing to be single she has joined ‘the most reviled mob in the Islamic world, the company of free, independent women’. Her brother has become a harraga (‘path burner’ in Arabic), a runaway risking everything for the chance of a better life elsewhere. If a harraga survives the journey, he or she burns their bridges and their identity papers.

The paediatrician’s ordered existence is shattered when she opens the reinforced steel front door to a stranger, a scatty Lolita figure in punk finery; 16 years old, penniless and pregnant. Chérifa brings a message from Lamia’s missing brother and demands temporary shelter.

Lamia is appalled by her stroppy, unwelcome guest, but increasingly envies her fearlessness. From grudging admiration grows an overwhelming drive to protect this free spirit and her unborn child in a world where women who are not subservient can pay the price with their lives. When Chérifa vanishes, she sets off on a rescue mission.

Lamia is the product of a patchwork of cultural influences — Dante, pop music, fairy tales, movies, Lewis Carroll and Victor Hugo, and her narrative swings between the cerebral and the streetwise; demotic clichés, literary allusions and lyrical descriptions, translated from the French with verve by Frank Wynne.

As the increasingly distraught woman leads us through the various hells of Algiers, characters proliferate: quirky, cynical, sometimes repellent. Stories emerge, sharp with black humour; it’s a crowded, meandering path. Between genuine danger and wild fantasy, Lamia risks losing her mind, hyper-ventilating, catastrophising tragic denouements as she searches for the girl she has come to love.

Algeria is not an easy country to pigeonhole, with a constitution more honoured in the breach than the observance, widespread corruption, public apathy and growing Islamisation. Sansal anatomises this turbulent society with a forensic eye, lamenting what has been lost, fearful of the future. Harraga is described as a novel, but in a Note to the Reader Sansal tells us:

The characters, the names, the dates, the places are real and so [this book] speaks only of the wretchedness of a world which no longer has faith, or values.

A true story then. At its heart an indictment of both authoritarian government and fundamentalism, and the threat both pose to women.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £14.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in