The Mediterranean glows in our conception of the Continent, the warm source of everything that is best in us, the seat of civilisation, from which one delicious wave after another has washed up on our shores.

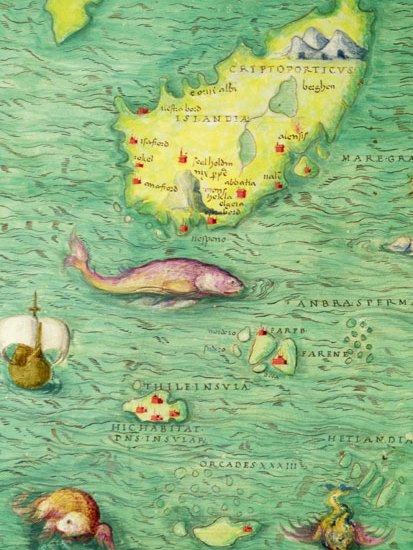

But what about the Mediterranean’s twin, the other great lobe of the Atlantic which defines the northern edge of the European peninsula, a sea of enormous fertility, its edges laced with islands, fed into by the richest of rivers, with, in the Baltic, its own inner chamber, giving access to the giant hinterlands of Russia. Surely the North Sea deserves its human history too?

That is Michael Pye’s question: do the North Sea and the connections across it constitute the missing half of the European story? How have its dynamics shaped our history? But more than that, is the north merely the ragged edge of the south, far less continuous in its culture, broken by a hostile climate and impoverished soils, the rough end of Europe? Or does it have a substance beyond that? Can you really say that ‘the North Sea made us who we are’?

He has posed it as a whopping set of questions, stretching over 1,000 years from 700 to 1700, and 100 kingdoms, one which would daunt any historian, however practised and however informed. Pye admits early on that he feels out of his depth and that, unfortunately, in the end, is the trouble. He doesn’t know enough to make a coherent case for the contribution the north, let alone the North Sea, may have made to European civilisation.

‘The modern world is taking its shape,’ he concludes after his centuries have run their course:

Law, professions, the written word; towns, and what they do to the natural world; books and fashion; business and its relationship to power. We are not on the margins of history any more; we are dealing in the essential, the changes of mind that made our world possible.

That is a good summary of what he has described — in essence, the medieval urbanisation of northern Europe — but not a single one of those aspects of life was not a reflection of what had already been long apparent in the south. A professionalised, urbanised and commercialised world is the grand legacy of the Mediterranean — the astonishing Phoenician-Greek-Roman-Byzantine-Arab-Venetian-Turkish continuity you can know and feel today in any harbour town from Cadiz to Latakia. The success stories of early modern capitalism, from the Hanseatic League to Venice, Antwerp and Genoa, are all part of the same set of understandings. Everything about them is European; nothing in that list distinguishes north from south, except perhaps for the lateness with which it made its way north.

Crucially, Pye has zero understanding of the way in which square-sailed ships — the ligaments of this culture — actually worked. ‘Since nobody could yet tack into a headwind,’ he writes of northern European sailors in the centuries before the Vikings, ‘each journey had to wait for the right wind to blow the ship forwards.’ Decades of research into the sailing patterns of square-rigged ships (which were known in the North Sea and Baltic from at least 300 BC, and maybe some 500 years earlier than that, to judge from Swedish rock carvings) has established that they could make progress to windward at about 2½ knots: 50 miles a day of distance made good; Bergen to Ipswich upwind in less than a week. But as Pye thinks that square-sailed ships cannot sail upwind, and does not know the place that dead reckoning has in navigation, he simply leaves that out.‘This cold, grey sea in an obscure time made the modern world possible,’ Pye maintains, but he brings no evidence to show that is true. And the problem lies deeper. There is no description here of the sea itself as an environment; nowhere an account of the counter-clockwise gyre of currents that until the age of steam always dominated shipping in the North Sea; no picture of the winds or their seasonal pattern; no mention of the major climatic shifts in his period, the first around AD 800 (an improvement), the second the atmospheric cooling around 1250, which brought malnutrition and continent-wide catastrophe in its wake; no concern for the key part played by the North Sea’s islands and archipelagos, nor why, for example, for centuries most of Europe’s whalers came from the islands: Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, the Lofotens, the Frisians. There is nothing anywhere in the book about the productivity of the sea itself, even its geography, the banks and shoals around which so much human life on the sea has centred, no reflection on the tidal patterns in the narrows, no real thought given to the sea as a human environment.

No understanding of the environment and its major changes and no understanding of the core technology which allowed people to cross and exploit that environment leaves the reader a little uncertain of his ground. And that lack of understanding proliferates. It is wrong to say that peasants could never own land in feudal Europe. Puffball mushrooms grow in pasture not in woods. Maybe fishermen in the Middle Ages ‘did a great deal of praying, and a fair amount of pilgrimage’, but it is simply untrue that fishermen were more devout than land peasants. A working law does not depend on the written word and there is no connection between literacy and legality (the whole of the complex legal structures of early medieval Iceland depended on talk and memory); it is not true that peat ‘keeps in the carbon dioxide essential for photosynthesis’; nor that joint stock companies were needed to drain the coastal wetlands. That huge effort was an almost exclusively ecclesiastical enterprise in the Middle Ages. And the idea that grandees stopped wanting to demonstrate their control of the landscape after about 1600 is quite clearly wrong.

I don’t want to be a spoilsport about this, but I have rarely read such a frustrating book. Pye has gathered a huge number of colourful moments from his reading, all carefully annotated, and has some fascinating passages on the realities of sex, disease, trade and religion in his chosen territories, but there is scarcely a number in it, let alone a chart. The endpaper maps are almost absurdly wrongly printed, leaving out every river and the site of every town. Its mass of storytelling, allied to a rather cute way with a moral (‘The personal isn’t just political; it is economic’; ‘before there were passports …your identity was lived in the present tense’) leaves you hungry for system, rigour, the search for pattern and consistency, any form of understanding which goes beyond the charming anecdote.

The question which a book of this kind needs to approach is the relationship of nature and culture. Which matters more in the making of human destiny? How does technology shape that meeting of people and world? And a more particular question hangs over this one: why did riches and power migrate northwest in Europe over the centuries this book addresses, largely leaving the Mediterranean for the North Sea? The largest GDP per person in AD 1000 was in Iraq, Iran and Turkey, by 1500 in Genoa and Antwerp, and by 1700 in Amsterdam and London. Why? Could it really have been the protein storage capacities of salt cod? Surely not, particularly when it is thought that even in the 16th century, international trade represented at most 2 per cent of European GDP. Everyone was still farming. The North Sea still awaits its Braudel.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033. Adam Nicolson’s books include Sea Room and The Mighty Dead: Why Homer Matters.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in