Would musical history have turned out differently if Alexander Glazunov hadn’t been smashed out of his wits when he conducted the first performance of Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 1 in D minor? The best of Glazunov’s own neatly carpentered symphonies hover on the verge of greatness. Perhaps if he hadn’t been such a toper — swigging from bottles of spirits during lectures at the St Petersburg Conservatory, where he was director — they would do more than hover. Unfortunately, his drinking didn’t just screw up his own career.

The 23-year-old Sergei Rachmaninov had spent two years working on his first symphony, whose climaxes erupt from melodic cells borrowed from Orthodox chant. Not that Glazunov would have noticed. He barely glanced at the score before the premiere. On that fateful evening in 1897 he conducted ‘like a zombie’, according to one account. The orchestra was all over the place. Poor Rachmaninov hid on a spiral staircase while it was going on and then ran into the street to escape the catcalls.

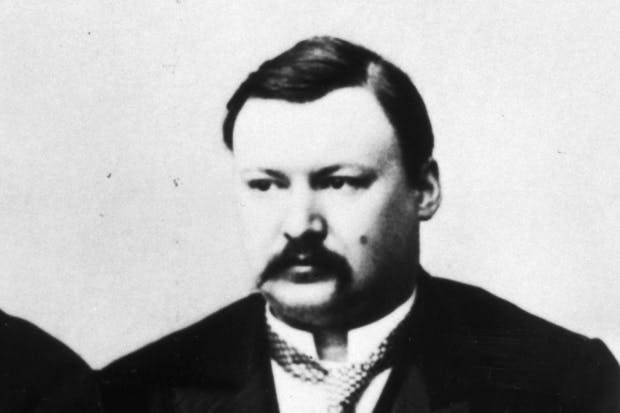

Composer, conductor and drunk Alexander Glazunov. Photo: Getty

Composer, conductor and drunk Alexander Glazunov. Photo: Getty

Posterity doesn’t lay all the blame at Glazunov’s door. The conventional wisdom is that, even in a fine performance such as Ashkenazy’s with the Concertgebouw, the work is a sprawling mess, exciting in places but basically one of music’s shipwrecks.

Nonsense. Yet again I find myself turning to Mark Morris, whose Methuen Guide to 20th-Century Composers (350 of them, expertly dissected) is one of four indispensable surveys of the music of the last century, the others being Norman Lebrecht’s enchantingly bitchy Complete Companion to 20th Century Music, Alex Ross’s The Rest is Noise and Ivan Hewett’s Music: Healing the Rift. Don’t get me started on what a scandal it is that Morris is out of print, though if you hurry you can find it second-hand on Amazon. This is his verdict on the First Symphony:

One of Rachmaninov’s finest works, heroic in tone, obviously indebted to Tchaikovsky and Borodin, but constructed with a flow of symphonic purpose and devoid of the kind of nostalgic limpid beauty that pervades his later work. The slow movement has real menace… evolving to an almost Mahlerian intensity and scope, the finale that Russian blaze of uplifting glory combined with darker dramatic urgency… It achieves what Glazunov’s own symphonies so often unsuccessfully attempted.

Ha! That’s a well-deserved dig at Glazunov, but it doesn’t alter the fact that it was ten years before Rachmaninov found the nerve to write another symphony, by which time he had the triumph of the Second Piano Concerto behind him. The Second Symphony is beautifully composed, full of good tunes — but they’re gloopy tunes of the type that make the concerto so lovable, if you like that sort of thing. I do, as it happens. You can’t help wondering, though, what might have happened if the First Symphony had been a success. Instead of throwing away his copy of the score (the orchestral parts were discovered by accident during the second world war and the work received its second performance in 1945), Rachmaninov might have gone on to write seven or eight symphonies. We’d have a Russian cycle to rival those of Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Jaunty sarcasm and wrist-slitting bleakness are all very well but it would be nice to have an alternative.

Anyway, you can make up your own mind when the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Jurowski play the First Symphony at the Festival Hall as part of their Rachmaninoff: Inside Out season on 3 December. Why they insist on spelling the composer’s name with two ‘f’s I don’t know. Also, given that the series includes all his works for piano and orchestra, it’s a shame that none features the greatest living interpreter of the concertos, the British pianist Stephen Hough, whose de-glooping of numbers Two and Three on Hyperion is a revelation. That said, Inside Out, which runs until April, promises to be a fascinating ‘journey’ (as we must now refer to all artistic projects). Rachmaninov eventually moved on from the exquisite sentimentality of his middle years. His late Symphonic Dances are lean, jazzy, tautly constructed — and contain bursts of savage exuberance that take us back 43 years to the First Symphony, from which he briefly quotes. Finally he was ready to acknowledge its merits — though it was a secret gesture, given that he thought the piece was irrecoverably lost.

Anyone who sits through all the LPO concerts will hear the development of an intriguing, elusive composer — and a great one. This is not what the pianist Alfred Brendel once loftily described as ‘music for teenagers’. That sort of snobbery now seems far more old-fashioned than anything written by Rachmaninov. And, as a footnote, let’s not forget that Rachmaninov was one of the supreme pianists of the 20th century. On YouTube you can find him playing his arrangement of Kreisler’s Liebesleid. In the 93 years since it was recorded no one has matched its perfectly suspended rubato. Listen to it and weep.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in