Austria is one of those nations which is known by everybody, but visited by few. Though considered to be within the very epicentre of Europe, economically, culturally and technologically it’s a nation living in and on its past. I was in Austria to research a book about an amazing Australian, born in and exiled from Vienna who went to Shanghai in China, and after the war, given a safe haven in Sydney.

Vienna can almost be defined by one of its most famous cultural institutions, the Sacher Torte. For those who don’t possess a sweet tooth, it’s a chocolate cake, invented by the Austrian chef Franz Sacher in 1832 for Prince Wenzel von Metternich. Coated on the outside by a thick layer of delicious dark chocolate, on the inside, the cake is tooth-rottingly sweet. It’s one of the main selling points of the Hotel Sacher in the centre of Vienna, a fussy establishment whose looks and manners define a previous age.

While surrounding nations have led the charge to modernity in the 21st century without undermining the glories of their past, Vienna seems unable to emerge from its history. In the 1930’s, before the Nazi takeover, Austria was one of the cultural and social capitals of Europe. And that’s still visible today, where every second lamppost carries a poster advertising a concert in one of the many palaces dedicated to the music of the Strauss family or Mozart, the city’s most famous inhabitants.

When the subject of my book was born here in the mid-1920’s, Germany was flexing its muscular wings after the disaster of the First World War. The Austro-Hungarian empire had collapsed, and a majority of Austrians hoped that their nation would be carried along on the coat-tales of Nazi expansionism. Ninety years later, sitting on the balcony of the Hotel Sacher and watching the horse-drawn carriages carry elegant Viennese from a Mozart concert in the Staatsoper, I couldn’t help but wonder whether the grandchildren of those who welcomed in the Nazis are still hoping for Germany to lead them into the future as they watch the industrial and commercial powerhouse of their neighbor again become the leader of Europe.

How very different from Vienna, though, is Shanghai. This was the only place in the world available to Jews who managed to escape the Nazi Holocaust. Despite the Evian Conference in 1938 attended by 32 of the world’s leading nations, which decried the Nazi crimes against the Jews, not one country offered to open its doors to the millions desperate to leave Germany and Austria. Only Shanghai offered Jews a safe haven, and tens of thousands of Jews came here and established a home in relative safety, despite the city being occupied by the Nazi’s allies, the Japanese.

Unlike Vienna, which is living its past in its present, Shanghai is furiously replacing the past with the future. I was last here three years ago, and one of the places I visited was the upper reaches of the television tower in Pudong, the highest building for miles, to look over the landscape of the vast megapolis. Today, the tower is surrounded and dwarfed by massive skyscrapers where the cost of a square meter is equivalent to the national debt of a small European country. The rapidity of development in Shanghai is breath-taking.

Building sites, cranes, and construction gangs are everywhere in Shanghai. Any old neighbourhood, where generations of families have lived for centuries, will be gone by tomorrow and the residents relocated, despite the social and cultural disruption. But the one area which remains intact is where the Jewish refugees, who arrived on tramp steamers and liners, were settled. They landed on the famous Bund which has hardly changed in 100 years and still reflects its glorious past as the home of banking, commerce and finance in this formerly international city.

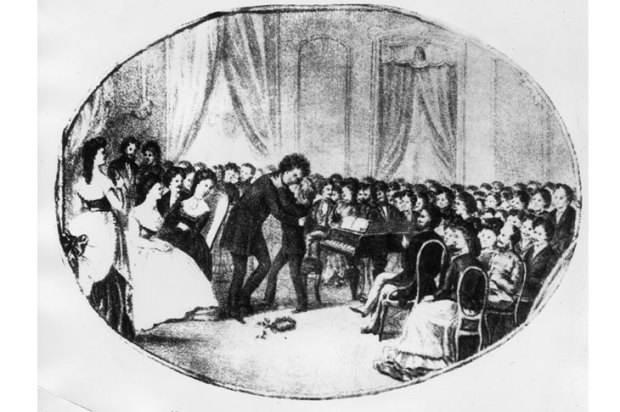

Shanghai became the Noah’s Ark for Jewish survival of the Holocaust, and the European residents of the ghetto brought their culture with them, much to the bemusement of their Chinese neighbours. The refugees lucky enough to escape before the Nazis closed the borders, who came mostly from Austria and Germany, established theatres, cafes, dance halls, orchestras, newspapers and social clubs. Entire families often lived in single rooms, and walked miles to their jobs in order to earn enough to afford to leave the ghetto. All this happened when both the Chinese and refugees were living under Japanese occupation. There was intense pressure imposed by the Japanese and Nazi authorities on the Chinese to carry out the Meisinger Plan to exterminate the Jewish refugees in Shanghai, but the Chinese, at considerable risk to themselves, refused to participate in mass murder. The Jewish refugees and their Chinese neighbours lived in harmony, despite their cultural differences, and today’s Shanghai authorities proudly promote their sanctuary as a tourism and educational resource. Just weeks ago, the museum erected a huge bronze wall with the names of all the Jewish refugees whose lives were saved by the openness and humanity of the Chinese authorities.

I phoned Qantas’ office in Shanghai on the day that I returned to Australia. I hung on for twenty minutes but never managed to speak to a single human being. However, I was entertained by a recording of a Chinese lady with the most melodic and beautiful soprano voice, singing to me ‘The Load to Gundagai,’ swiftly followed by ‘Moon Liver.’ A miracle of cultural confusion.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Alan Gold’s latest novel is ‘Bloodline’ (Simon & Schuster Australia).

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in