Kenya’s second-largest city, Mombasa, is the sprawling home of some 3.5 million people on the nation’s east coast. Situated on the Indian Ocean, it has been a major East African trading port for centuries. It was successively ruled by the Omanis and the Portuguese who constructed the old town’s world heritage-listed Fort Jesus in the late-1500s. The UK subsequently governed the country from 1888 before independence was achieved in 1963 following the Mau Mau uprising. Having lived through subsequent years of undemocratic rule, including a one-party system, Kenyans have been searching for a fair and just state. In 2010, they approved a new constitution with a presidential system of government, along with two houses of parliament.

I visited Kenya to participate in their regular post-election parliamentary seminar. The 349 members of the house and the 67 senators gathered in Mombasa for the week-long induction and training program. I was one of the mentors participating under the auspices of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, which conducts training sessions throughout the Commonwealth.

The home of 55 million people, Kenya is sub-Saharan Africa’s third- wealthiest nation. The warm and friendly people value their democracy although there are still many challenges, both for the country and the region. Conflicts in bordering Somalia and terrorism remain a threat. An ongoing and serious drought and its impact on the economy are significant issues for the nation.

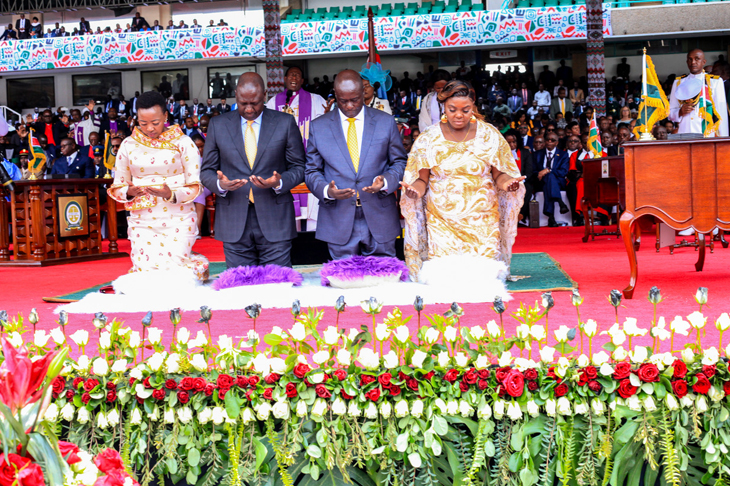

The seminar was chaired by the parliament’s presiding officers and opened by President William Ruto who narrowly won the national election last year. His polished presentation was redolent of a long-term parliamentarian and minister.

There is a directness among Kenyan parliamentarians about the issues facing the nation. Paramount among their concerns was their system of government, the balance of Assembly and Senate responsibilities and role of members and senators.

While the Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong was delivering a speech in London bemoaning the colonial history that included her grandmother working as a domestic servant in Borneo – which led to her father studying in Australia under the Colombo Plan and she holding one of the most important offices in the nation – Kenyan parliamentarians were discussing the possibility of returning to a Westminster parliamentary system.

Far from condemning the UK for past failings, the Kenyans were debating how they could attain some of the benefits of a parliamentary system that they had lost under a presidential model of governance. In particular, the Kenyans were yearning for a system that provides for the regular questioning of ministers, something that is missing from their constitutional arrangements. In his speech, the President recognised this desire, committing to questioning of his cabinet secretary. Many MPs expressed the desire this arrangement went further to allow questioning of all ministers. They regard the absence of committee hearings at which ministers and senior public servants appear and answer questions about the conduct of their portfolio as a deficiency in their system.

They also look on Question Time, as it operates in parliamentary systems, as a useful activity, although I pointed out that there is more theatre than substance in Australia’s version of the practice.

A second contentious issue is the respective responsibilities of the Assembly and the Senate. Under the Kenyan constitution, the National Assembly ‘determines the allocation of revenue between all levels of government… allocates funds for expenditure by the national government and other national State organs, and exercises oversight over national revenue and its expenditure’.

The Senate, which represents the 47 counties, ‘determines the allocation of national revenue among counties… and exercises oversight over national revenue allocated to county governments’.

This formulation has resulted in disputes about the total and specific allocations to the counties. In addition, the Assembly has broad legislative powers, but the Senate also considers, debates and approve bills concerning counties. The potential for conflict is patent.

A third area of contention has been the distribution of funds to organisations and individuals after the Supreme Court struck down provisions which distributed some funds through MPs. In an action that would never occur in the Australian, Canadian or UK parliament, a Kenyan Supreme Court judge addressed current national issues at the seminar and answered questions from sometimes hostile MPs.

These debates reflected a healthy democracy at work. Discussions about how other Commonwealth nations addressed similar issues were welcomed by the Kenyan representatives.

Far from the Commonwealth being ‘Empire 2.0’ as described by Prince Harry, I encountered genuine affection for the ongoing affiliations and an appreciation of the work of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. Even when former British colonies became republics, most valued their ongoing involvement in the Commonwealth. The association’s regular training academies are one example of the continuing value of the Commonwealth.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in