Strange things happen to Werner Herzog — almost as strange as the things that happen in his haunting, hypnotic films. In 1971, while making a movie in Peru, he was bumped off a flight that subsequently crashed into the jungle. Years later, he made a moving film about that disaster’s sole survivor. In 2006, while filming an interview with the BBC in Los Angeles, he was shot in the belly by some nutter with a small calibre rifle. Most film-makers would have been turned to jelly by this terrifying interruption; Herzog simply laughed it off, cheerfully dropping his trousers to reveal a bleeding bullet wound, and a natty pair of Paisley boxer shorts.

‘He has become a catalyst for extraordinary events,’ says his British producer Andre Singer. He’s done some strange things, too. While filming Aguirre, the Wrath of God (a dark, disturbing film about the conquistadors, shot entirely in the Amazon with a camera he stole from the Munich film school), he promised to kill his leading man and lifelong friend, Klaus Kinski, if the actor left for home before Herzog finished filming. Kinski huffed and puffed, but he could tell the director wasn’t joking. He stayed until Herzog was through.

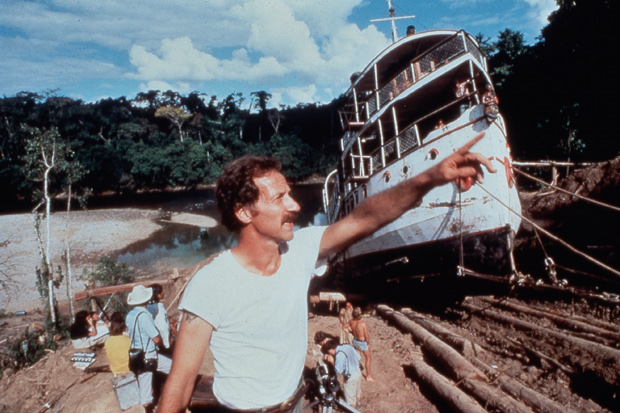

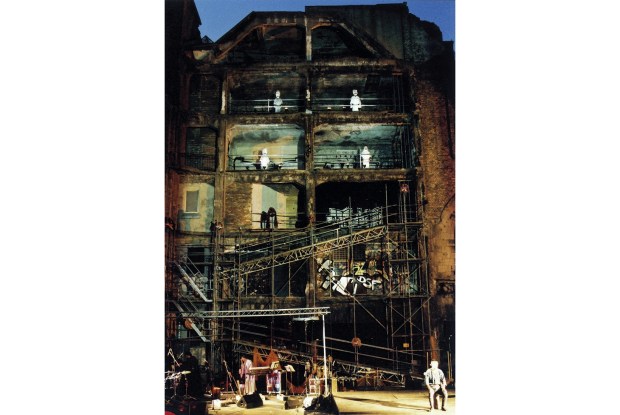

Filming Fitzcarraldo, another Amazonian epic, also starring Kinski — this time as an opera fanatic who hauls a steamship over a mountain — Herzog insisted on recreating this Herculean feat for real. ‘If I abandon this, I would be a man without dreams,’ he said. ‘It is faith that moves mountains.’ No wonder he describes film-making as a battleground. ‘I think Werner is wired slightly differently to us,’ Singer tells me. ‘Once he has got images and a storyline in his mind, he will go and find them and make them work.’

Of course none of this would be of any interest if Herzog made mediocre movies. Film history is paved with the gravestones of obsessive but untalented auteurs. Yet, as anyone who knows his work can confirm, he’s an extraordinary film-maker. He says he doesn’t dream and wonders if his films might be a bid to make up this deficit. Like a lot of his odd pronouncements, this makes perfect sense. His films are lucid dreams, full of weird, arresting images, yet they have a profound internal logic. Like ancient myths or legends, there’s something timeless and elemental about them, as if the tales he tells have always been there — untold, unheard, unseen.

Werner Herzog was born in Munich in 1942. When he was just a few weeks old, his home was bombed and his mother took him to a remote village in the Bavarian Alps. Here, Werner and his brother saw out the war and the lean years that followed. His father was absent, a conscript in Hitler’s Wehrmacht. His parents later separated. He was raised by his mother, whom he adored. He was often cold and hungry, but his childhood was full of adventure and imagination. ‘We invented an entire world.’ He didn’t see his first film until he was 11 and made his first film when he was 19. In the 1960s he made his name alongside other West German film-makers such as Wim Wenders and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, a ‘fatherless generation’, all born, like Herzog, at the end of the Third Reich. The Nazis had destroyed German cinema. For these young film-makers, this was both a burden and an opportunity. They had to start again.

The Werner Herzog Collection, a new box set from the BFI, is a lavish survey of the first 20 years of Herzog’s career. It features 18 arresting films — both dramas and documentaries, though the dividing line is blurred. His best films fall between fact and fiction, neither fantasy nor reportage. With his use of untrained actors, his dramas always seem intensely real (‘I do not make a distinction between professional and non-professional actors — I just make a distinction between good and bad’). With their fictitious flourishes, his documentaries can feel more like dramas. ‘For him, truth can be a little bit more elastic,’ says Singer. ‘It’s an inner truth.’

For the MTV generation, raised on blockbusters, Herzog’s technique is a challenge. He always seems to hold a shot for a few seconds longer than you want him to, forcing you to pay attention, making you see things his way. Yet, once you’ve become accustomed to his languid style, more conventional films seem dull and shallow. He’ll go to any lengths to get the shot he wants, but his work is full of spontaneity. He shuns storyboards (‘a disease of Hollywood’) and often shoots single takes.

Not all his ideas come off. Heart of Glass, a somnambulistic film in which his cast perform under hypnosis, sometimes borders on the soporific. But when he gets it right the results are spectacular. In The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, about an idiot savant in Biedermeier Germany, he cast Bruno S., a damaged (but brilliant) man with no acting experience, who’d spent more than 20 years in various institutions. It was a controversial choice, but Bruno’s performance was a triumph. He went on to star in Herzog’s Stroszek, one of the most distressing, yet riveting, films I’ve ever seen.

The Werner Herzog Collection contains several fascinating extras, including Burden of Dreams, Les Blank’s documentary about the making of Fitzcarraldo. More than any other film, Fitzcarraldo has come to define Herzog, as a man and a film-maker: the heroic eccentric with a mad obsession, battling to create something beautiful in a brutal, godless world. ‘I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility and murder,’ he says. But his demented Meisterwerk offers us some hope. ‘The film always tries to give you courage,’ he says. ‘Dream! Fulfil it! Don’t be scared! Do it, no matter what!’ The big difference between Herzog and Fitzcarraldo is that Herzog has a sense of humour. This is what saves him from pomposity. His Fitzcarraldo memoir is called Conquest of the Useless.

Even at his most elegiac, he’s never pretentious or obtuse. One of my favourite films in this box set is Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, in which Herzog makes a wager with the film-maker Errol Morris. If Morris finishes his first film, Herzog vows to eat one of his boots. When Morris completes his project, Herzog duly cooks it (in a rich sauce, with lots of garlic) and sits down to eat it. ‘It’s easy to eat a shoe,’ he says. Much harder to make movies that change the way we see the world.

For me, the story that sums up Herzog’s unique world-view concerns the great German Jewish film critic Lotte Eisner, a concentration camp survivor and an early champion of his work. Eisner had lived in Paris since the war, having fled to France to escape the Nazis. In November 1974 Herzog was in Munich when he heard that she was dying. ‘German cinema could not do without her now,’ he declared. ‘I set off on the most direct route to Paris, in full faith, believing that she would stay alive if I came on foot.’ For three weeks he walked through rain and snow, without a proper map or winter clothing, trekking across muddy fields, following a straight line on his compass. ‘It was like a pilgrimage,’ he says. ‘I would not allow her to die.’ When he arrived at her bedside, Eisner was on the mend. ‘Open the window,’ he told her. ‘From these last days onward I can fly.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

The Werner Herzog Collection is released on DVD and Bluray by the BFI on 25 August.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in