The robber barons of the gilded age, at the turn of the 20th century, were the most ruthless accumulators of wealth in the history of the United States, and none of them was less handicapped by moral scruples than W.A. Clark. He was up there near the pinnacle of acquisitiveness with Rockefeller but was not as legendary in popular imagination. While other pioneers were searching for gold, Clark developed copper-mining at the most opportune time, when there was a great and growing demand for copper for electrical wiring. The copper lode he discovered in Butte, Montana, produced 11 million tons and earned the town its nickname ‘The Richest Hill on Earth’.

In those days, US senators were appointed by the state legislators, rather than elected. Clark got himself sent to Washington, resigned from the senate when there were allegations of bribery and, with suspicious ease, was reappointed. ‘He is said to have bought legislatures and judges as other men buy food and raiment,’ wrote Mark Twain. ‘By his example he has so excused and sweetened corruption that in Montana it no longer has an offensive smell.’

Whatever Clark’s ethical standards really were, he was an extraordinarily astute entrepreneur, who found that there was ‘no lack of opportunity for those who were on alert for making money’. Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr relate how Clark extended his activities to Arizona and collected banks, railroads and newspapers, to become a multimillionaire in his thirties. He indulged in personal extravagance and domestic grandiosity on a scale he hoped would gain him admittance to the high society of New York’s exclusive ‘400’, an ambitious achievement he was denied.

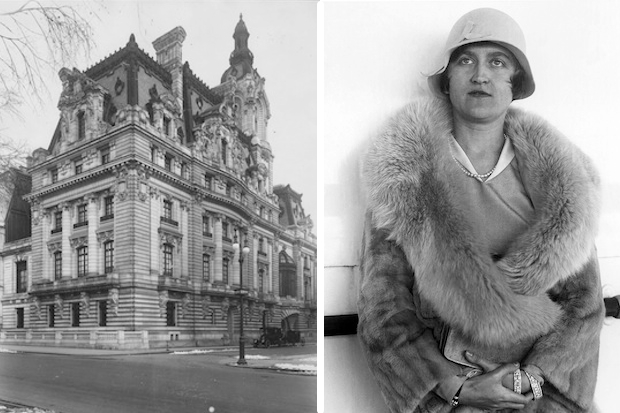

Clark spent the equivalent of $6 million in today’s money to build the most ornate house in Butte, locally called the Copper King Mansion. His wife, Dedman writes, ‘was known as a charming hostess, but she was not often at home’. She and their children spent most of the time in New York and Europe, ‘seeking cleaner air, better schools and cultural opportunities’. When she died at the age of 50, Clark built her a $150,000 mausoleum like a Greek temple in Woodlawn cemetery, in the Bronx. Then he installed his second family in Manhattan’s biggest and most expensive mansion, which he built on Fifth Avenue at 77th Street, costing the present-day equivalent of about $180 million.

The authors translate all expenditures into what they would amount to now, for prices are the criteria by which they evaluate everything. They describe the Clarks’ habits and habitats both objectively and emotively in ways reminiscent of estate agents’ and fine-art auctioneers’ catalogues, the Sunday Times ‘Rich List’ and Hello! magazine, as if calculated to arouse awe and hopeless envy. The New York mansion contained 121 rooms, including a palatial 18th-century music room, the Salon Doré, which was bought in France and somehow shipped across the Atlantic, and five galleries housing Clark’s art collection and a $120,000 pipe organ.

The elder of Clark’s two daughters by Anna, his second wife, died a week before her 17th birthday, and Clark himself died in 1925 at the age of 86. The mansion was considered too big for his widow and their younger daughter, Huguette, who was born in Paris and named after Victor Hugo, so in 1927 it was demolished, having been inhabited for 14 years.

Clark left his paintings to the Metropolitan Museum and the Salon Doré to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington. Anna, accompanied by an elderly aunt and Huguette, moved to 15,000 sq ft luxurious apartment building five blocks down Fifth Avenue. After a charmless, probably arranged marriage to a 23-year-old law student that lasted only a year, Huguette divorced him and stayed with her mother, where there was nothing much to do. Dedman quotes the 1940 census to give the names, occupations, ages, marital status, countries of origin, wages and education of all 10 of the staff in residence. Huguette was a competent, unoriginal painter and an avid collector of dolls, particularly Japanese, and of custom-made doll houses.

Mother and daughter enjoyed brief sojourns at a new acquisition, Bellosguardo, a splendid estate on the waterfront at Santa Barbara. When many Californians feared a Japanese invasion soon after Pearl Harbor, the Clarks purchased a smaller place, securely inland, and later donated it to the Boy Scouts of America.

After being profoundly saddened by her mother’s death, Huguette retained ownership of Bellosguardo and the New York apartment complex and Le Beau Chateau in Connecticut, which she acquired during the Cold War, when New York, she thought, might be bombed. She had these properties maintained by full-time caretakers and staff, at great expense, though she never again visited them.

The most interesting part of this inexorably materialistic, yet strangely hypnotic American bestseller is the account of shy Huguette’s voluntary isolation, in good health, in private Manhattan hospital bedrooms for the last 25 years of her life, with doctors and nurses constantly on call, at a cost of about $560,000 a month. The main contributions of Dedman’s co-author, Huguette’s cousin, are transcriptions of his telephone conversations with her, which, unfortunately, are very dull. Huguette was an active correspondent, rewarding writers of the most adoring letters with very large cheques, even some remote epistolary acquaintances she had not met. She frequently gave bonuses to her favourite nurse and family, altogether, in 20 years, amounting to more than $30 million. When this generous, eccentric heiress died, at the age of 104, the residue of her $300 million inheritance was still large enough to excite a flock of litigious vultures.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £15.29, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in