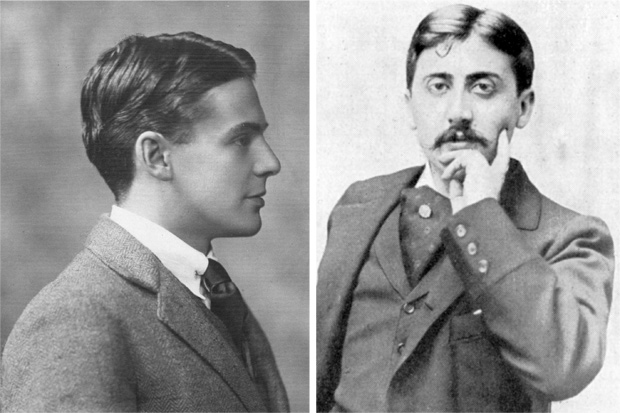

Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff’s Englishing of Proust — widely and immediately agreed to be one of the greatest literary translations of all time — very nearly didn’t happen. Scott Moncrieff only suggested the project to his publisher after they rejected a collection of satirical squibs in verse (sample: ‘Sir Philip Sassoon is the Member for Hythe;/ He is opulent, generous, swarthy and lithe.’). Like any good hack, he had another suggestion up his sleeve: there was this character Proust just starting to be published — making a bit of noise in France. Constable didn’t immediately see the value: ‘They replied that they did not see much use in publishing a translation of Prevost [sic].’ His sort-of mentor Edmund Gosse agreed: ‘Since you told me you were translating Proust I have not felt happy. Not here, O son of Apollo, are haunts meet for thee.’

Ah, hindsight. Translating Proust wasn’t all CK did in his astoundingly busy life. He also translated Pirandello and Stendhal, Beowulf, the Chanson de Roland and the letters of Abelard and Heloise. He wrote poetry and short stories and put himself about in the world of letters — even finding time to prosecute a long and pointless feud with Osbert Sitwell. Through these pages pass Robert Graves, G.K. Chesterton, Siegfried Sassoon, Joseph Conrad, Ronald Knox, Saki and George Moore and a very young Noël Coward. He was decorated for bravery on the Western Front, and worked as a British spy while living in Mussolini’s Italy.

Scott Moncrieff (the non-hyphenated double-barrel is characteristic of Scottish nobility, apparently) grew up in grand houses amid a fug of respectability in Scotland. He was a precociously swotty kid, volunteering a critical opinion on Milton’s ‘Nativity’ ode at the age of four. He won a scholarship to Winchester, and fell in with the literary and homosexual circle in London surrounding Oscar Wilde’s friend Robert Ross and his private secretary Christopher Sclater Millard. Towards the end of his time at school he published a short story, about adolescent homosexuality and adult hypocrisy on the subject, that got him in hot water with the head-master and may have been what scotched his hopes of going on to Oxford.

In some sense this is a work of family history. CK was Jean Findlay’s mother’s great-uncle, and in preparing this text she has been able to draw on ‘a battered leather suitcase containing [his] forgotten letters, diaries, and notebooks’. What a trove to work from. More than that, as she confesses in the introduction, she had actually finished writing the book when she came across something that changed the whole cast of her understanding: 458 pages of private letters and postcards to his lifelong friend Vyvyan Holland (Oscar Wilde’s son). She had thought CK celibate. Here was evidence to the contrary: Vyvyan was the only person, it seems, to whom he wrote frankly about his sex-life.

CK’s was a short life — stomach cancer got him at 40 — and he was half dead before his real work began: badly wounded fighting in the first world war. He was by all accounts a model officer: brave as all hell and unfashionably convinced of the nobility of the enterprise. Nevertheless, ‘Shakespeare’s birthday and the day Rupert Brooke had died, 23 April, was the day Charles’s life was cut in half by friendly fire,’ writes Findlay. A shell fell short and exploded near him. His legs, he wrote to a friend, ‘gave way beneath me like a trayful of claret glasses’.

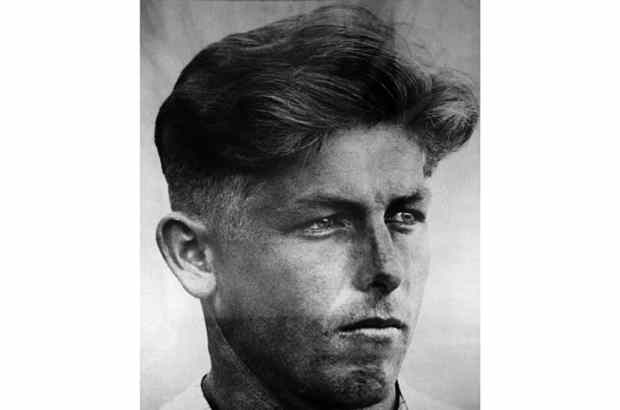

He narrowly avoided losing his left leg altogether, and was seriously lamed for the rest of his life. He had trench foot, trench fever and barely a tooth of his own by his mid-twenties. He also lost many close friends to the war — including his lover Philip Bainbrigge and his friend Wilfred Owen. It’s clear that CK was in love with Owen, but — though he was rumoured at the time to have seduced him — the balance of probability is that they were not lovers. Their intercourse was literary. CK admired and championed Owen, and they bonded (really!) with a fierce intensity over their mutual interest in assonance and pararhyme.

The biographical chapters of this book — geneaology, schooldays, wartime, literary life, spying (we know the fact of it but not much detail) — are well handled and by and large interesting. You need to wait until about two thirds of the way through, though, for it really to catch fire, which it does when Findlay turns her sensitive attention to the business of translation. CK’s extraordinary way with Proust’s prose, she suggests, came from a deep personal affinity. He shared not only Proust’s homosexuality and his Catholicism (CK converted in France while posted to the Western Front) but ‘an affinity with the same literature, a passion for genealogy and aesthetic appreciation […] he had lived through the same events and, like Proust, had witnessed the end of the century’s Victorian legacy […] and he travelled often in Europe during that time.’ There is wonderful detail on what that meant at the level of the sentence — on Proust’s response to the translation (he was more or less on his last legs when he got it) — and on its immediate impact on the literary world.

So much of what we think or know about Proust comes from CK: even down to the English titles he gave the books — I didn’t know that Swann’s Way came to him via Beowulf (swans weg), for instance. And Proust’s profound influence on stream-of-consciousness writing in English, Findlay argues plausibly, was down to CK. Two James Joyce coinages cannot but have come from CK’s version (‘pities of the plain’, for instance, puns on Cities of the Plain, the circumspect title CK gave Sodome et Gomorrhe). Virginia Woolf told Roger Fry that she found reading the translation something akin to a sexual experience. So did CK, it seems. In something of a marmalade-dropper, Findlay quotes a letter to Vyvyan saying how easy it is to translate Stendhal: ‘You can do it straight on to the typewriter without even stopping to masturbate, as in the case of Proust.’

The letters to Vyvyan see off for good the idea — perhaps easy to catch — that CK must have been some neurasthenic aesthete too delicate for this world. Here too was a great joker, a writer of childishly bawdy verses (‘The Bishop of Birmingham buggers boys while confirming ’em/ The Bishop of Norwich makes them come in his porridge,/ The Dean of West Ham smears their bottoms with jam’) who jokes about putting his nephew into the Tube (‘better than putting one’s tube into a nephew’) and doodled an ejaculating penis on the title sheet of his Abelard and Heloise translation. God, he was young!

And his productivity was astonishing. As Findlay puts it, the pattern of his life was ‘bouts of innocuous dissipation interspersed with long stretches of very hard work’. We find him translating 3,500 words of Proust in a single day and 2,500 words the next. At another moment he writes to a friend that he’s in the midst of correcting half a million words in two weeks. Did that workrate mean he was slapdash? Apparently not: he was spotting compositors’ errors in the French texts as he went along.

One mistake did pain him, though. ‘I made an absurd blunder over chapeau melon,’ he wailed in a letter. The correct translation is ‘bowler hat’. He rendered it: ‘melon hat’. It was changed in the second edition, but I rather think it’s an improvement. As they say on the Tour de France: chapeau!

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in