Few subjects generate as much angst, or puzzlement, among Western policymakers in Africa as China’s presence on the continent. In his new book, China’s Second Continent, the American journalist Howard French recalls meeting US officials in Mali to sound them out on the matter. Instead, he finds himself barraged by questions. ‘It would really be useful for us to know what the Chinese are up to,’ one American official tells him. ‘So far we’ve been limited to speaking with them through translators. We’ve got very little idea about any of this.’

Grasping the range and scale of China’s activities in Africa is indeed a tall order. Commercial deals are cloaked in secrecy. Immigration statistics from African countries are poor. And contrary to some perceptions, the Chinese in Africa hardly move as a bloc. Many live deep in the hinterlands, toiling in small-scale mining or petty commerce.

The upshot, as French rightly notes, is that mere statistics are hopelessly inadequate to capture the China-Africa relationship. Understanding what the Chinese ‘are up to’ requires going out and meeting them. A lot of them. Low-end estimates peg their numbers in Africa at around one million. The true number, in all probability, is significantly higher.

Fortunately, French is the ideal man for the job. The former West Africa and Shanghai bureau chief for the New York Times, he speaks Chinese, French and Spanish. His linguistic prowess and intrepid travel regimen — he visits 15 countries in all — win him access to Chinese migrants from every walk of life, from a French-educated elite commissioned to build a 32-storey tower in Dakar to an electronics vendor in an isolated Mozambican village who explains that she ‘discovered the country online’. The result is a colourful and revealing collection of anecdotes culled from interactions planned and impromptu.

What does French learn? For one thing, China’s African story is no flash in the pan. Though migration is encouraged and heavily subsidised by Beijing, the process tends to unfold in much more organic — and probably sustainable — ways. Frustrated by cramped living conditions and stifled economic opportunities back home, many Chinese see Africa as ‘a place of almost unlimited opportunity’. Word of mouth and the internet have created chains of migration to even the most remote corners of the continent.

The migrants can be some of the harshest critics of their homeland. Yet they proudly trumpet the Chinese characteristics to which they ascribe their success in unfamiliar terrain. Many cite their willingness to ‘eat bitter’ in enduring early hardships. And they exhibit some of the same ruthless ambition as their government. One man in Mozambique tells French about his plan to fix his son up with local girls. ‘The mothers are Mozambicans, but the land will be within our family,’ he explains. ‘Do you get it? This means that because the children will be Mozambicans they can’t treat us as foreigners.’

French is at pains, perhaps overly so, to be even-handed. Several Africans he speaks to express appreciation for China’s ‘no strings attached’ investments in contrast to the conditionality that accompanies western dollars. One Malian praises China’s patience, also in contrast to an easily distracted West: ‘They are like a boa: it observes its prey quietly, taking its time. In the same way, the Chinese are waiting for a long-term return.’

But as the tale unfolds, the evidence amasses inexorably that the prey is too often Africa itself. Chinese businesses shun local workers in favour of their compatriots. Bankrolled by easy credit from state banks and allegedly shielded from police crackdowns over environmental or labour violations by cosy relations between Beijing and government officials, they easily undersell and underbid their African competitors. Pervasive racism underlies it all. In the end, French is forced to confront the question of whether China’s activities in Africa at least constitute a kind of proto-colonialism, to which he replies with a qualified yes.

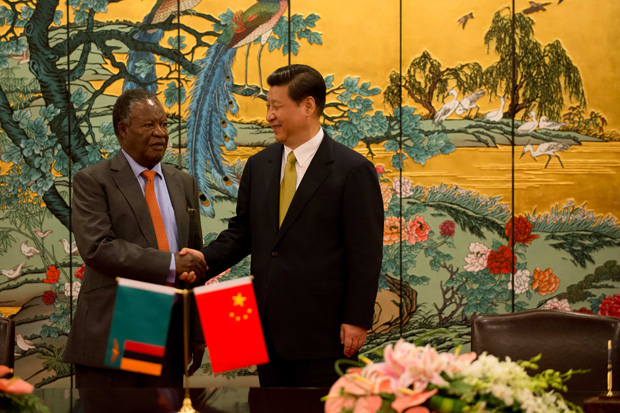

Mounting frustration with Chinese behaviour is finally showing signs of coalescing into something concrete. In Zambia, Michael Sata, a strident critic of Chinese policies in the country, won the 2011 presidential election after three unsuccessful bids. But even Sata has had to make peace with reality. Three days after his inauguration, Sata granted his first diplomatic audience — to the Chinese ambassador.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £21. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in