To Paris, for the launch of the French edition of my novel about the Dreyfus affair. As we land, I isolate three anxieties out of my general sense of unease. First is the natural nervousness of any Englishman contemplating telling the French anything about their own country. Second is the French law which allows the descendants of actual historical figures — of whom there are dozens in my novel — to sue for defamation: the heirs of the Marquis de Sade even objected to an unflattering portrayal of the inventor of sadism. Third, I am required to make a speech in French, and while my grasp of that language is not as bad as my sister-in-law’s — who once genuinely inquired, at a restaurant in the Var: ‘What is the French for ratatouille?’ — it is, let us say, un peu mauvais. I have in my pocket an anecdote from the diaries of the private secretary of King George VI, Sir Alan Lascelles, recounting how Churchill was overheard berating de Gaulle during a heated wartime argument: ‘Et, marquez mes mots, mon ami — si vous me double-crosserez, je vous liquiderai.’ I propose to say: ‘Je parle le français comme Churchill’ and hope the story will see me through.

To my surprise, I discover that aides of the French defence minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, have read the novel and approve of it, even to the extent of allowing a small launch party to be held in the hôtel de Brienne on the rue Saint-Dominique — the official residence of successive Ministers of War since 1787, and the setting for both the opening and closing scenes of my book. It is a strange sensation to follow in the footsteps of my hero, Colonel Picquart, past the sentries, across the courtyard, up the marble staircase — with its suits of armour and a version of David’s famous painting of Napoleon crossing the Alps — and into the very office in which, 119 years ago, Picquart described Alfred Dreyfus’s degradation ceremony to the then Minister of War, General Mercier. Even stranger is to encounter here Dreyfus’s grandson, Charles, now in his eighties and the spitting image of his grandfather. Later, he sends me a picture of them together, taken in a garden in 1934, the year before the old man died. He remembers a kind, quietly spoken, dignified person, which is exactly how the modern M. Dreyfus appears.

Also in the room is Roman Polanski, who is preparing to film the book. I introduce him to Dreyfus. Polanski, who was born in Paris in 1933, asks him how he survived the war. Dreyfus answers that his father managed to get the family on to the very last boat to leave France for the USA; sadly his cousin, Madeleine, was not so lucky: she died in Auschwitz. ‘So did my mother,’ says Roman. Through the window, I can see across the garden to the corner of the rue de l’Université, to the spot where the army’s secret intelligence unit, the Statistical Section, used to have its poky headquarters. That was where a group of anti-Semitic officers concocted the evidence that sent Dreyfus to Devil’s Island. The minister’s room, in the fading sunlight, is suddenly full of ghosts.

The minister himself arrives. A glass is tapped. Silence falls. The head of the publishers stands at a lectern and makes a speech. My editor follows suit. And then it’s my turn. I have never felt quite so nervous before speaking in my life. ‘Je peux lire le français, mais je parle le français comme Winston Churchill…’ My mouth dries. I tell the de Gaulle story. Nobody laughs. Too late I realise that of course the joke only works in English. Somehow I stammer my way to the end. ‘Avec les mots des spectateurs lors du procès de Zola: “Vive Georges Picquart!”’ This rousing finale just about saves me.

Years ago I was rung by a reporter and asked which actor would best portray me on screen. Unhesitatingly I replied: ‘Jacques Tati.’ The truth of this rare shaft of self-awareness became apparent immediately on my return from Paris, when I was called by a producer from Andrew Neil’s politics programme and asked if I would go on to talk about Tony Blair. ‘No thank you.’ I hung up and then wondered: why this sudden interest? The answer lay, as answers to the puzzles of modern life so often do, on the Daily Mail website: ‘Blair “is a man with a messiah complex who’s obsessed with making money”: Time in office made him mad, says former friend and author Robert Harris.’ Dimly, memories began to stir. A lunchtime in my drawing room some weeks earlier… A glass of champagne waving eloquently in the hand of ‘the former friend’… A young female reporter from a magazine called Total Politics, her tape recorder running… I make no complaint. The words were mine. But the post-prandial tone — as you can just about make out if you read the whole thing — was actually sympathetic, even regretful. Not that the former friend of the former friend will see it that way, I suppose, and his French is better than Churchill’s: ‘Je l’ai double-crossé, il me liquiderai…?’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

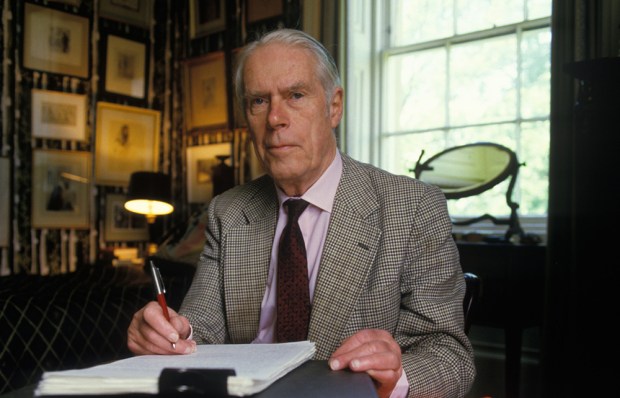

Robert Harris’s bestselling novels include Fatherland, The Ghost and An Officer and a Spy, just out in paperback. He’s also a former political editor of the Observer.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in