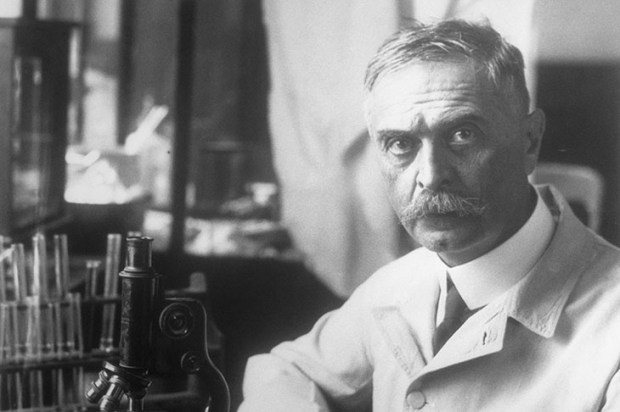

He was always lucky, and he knew it: lucky in the secure rural intimacy of the upbringing described in Cider with Rosie; in the love of some passionate, clever women, whose guidance and support get rather less than their due in As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning; and in having survived the Spanish civil war — the subject of A Moment of War — despite seeing action (though on his part this involved more seeing than action) in the terrible last battle of Teruel, and being imprisoned three times as a suspected spy. Behind and beyond all that, he was lucky in his gifts: charm, which included a knack for emotional escapology; artistic skill — he drew, painted and was an agile violinist; and above all verbal fluency. Has he been so lucky in terms of how what he left behind ‘stands up’?

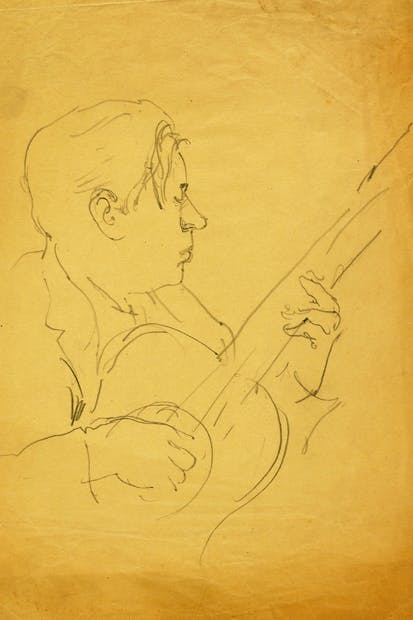

He thought he could have made a career as a visual artist, if only more people had liked his work (there’s charm in that self-deprecating idea, too). Some — perhaps most — of his art can be seen reproduced in Laurie Lee: A Folio (Unicorn Press, £24.95, Spectator Bookshop, £22.49) compiled by his daughter Jessy. The colours of the more studenty pieces are less brash in actuality than in reproduction and it’s hard to imagine anybody who wouldn’t be happy to have one of the later — 1950s on — portrait sketches on a wall. As for the violin (and guitar): the people, mainly but not all very poor, who heard him busking his way through mid-1930s Spain fed and housed him and gave him money; and there are still individuals around with warm memories of his playing in their parents’ London homes. Do any recordings survive?

The writing is what Lee’s reputation depends on, though. I was apprehensive about going back to Cider with Rosie 50-plus years after it came out, having loved it as a teenager, though not without noticing even then the one-or-two-a-paragraph similes which had such dire effects on his emulators.

Happily, the book has grown during its long intervals: not only between Lee’s post- first-world-war childhood and his writing about it in the late 1950s, but between both those times and now. Today, protestors are deploying him in their arguments against plans to develop Slad Valley, though what with the M5 and the light-industrial estates sprawled around the upper reaches of the Severn, the landscapes his book communicates have long seemed fictional.

So they always were, in fact. Part of his skill is in persuading us, first, of the reality of a world whose isolation mainly existed in his mind and, second, that it only began to change after he arrived there. The unbroken continuities he claimed to have known with ‘the blood and beliefs of generations who had been in this valley since the Stone Age’ are a wilful exaggeration. Stroud, three miles away — where until the first world war his subsequently absentee father managed the Co-op grocery — was an industrial town, home to the inventors of those twin facilitators of western modernity, the conveyor belt and the lawnmower. For 140 years before Laurie’s birth it had been linked to the rest of Britain by canal and for more than half that time by rail. When he set off on foot for London (via the south coast!), he knew perfectly well that the adventure was as artificial as Robert Louis Stevenson’s dragging his poor donkey through the Cévennes.

But practicality and literalism aren’t what we want from our romantics. Take the famous first stanza of Lee’s 1936 poem ‘Music in a Spanish Town’: ‘In the street I take my stand /with my fiddle like a gun against my shoulder, /and the hot strings under my trigger hand /shooting an old dance at the evening walls.’ It doesn’t matter that the fingering hand on a violin’s neck is positioned like the one supporting and aiming a rifle barrel, not squeezing the trigger. The lines are arresting because of their rhythm and the discord between war and music, the unobtrusive communication of atmosphere — the heat, the resonant walls of Cordoba — and, especially in this context, the ambiguity of ‘take my stand’.

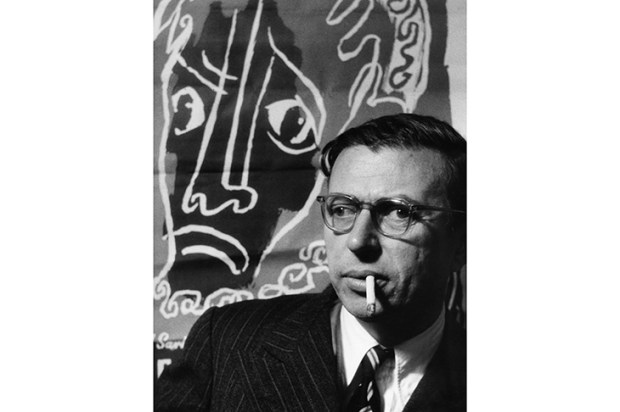

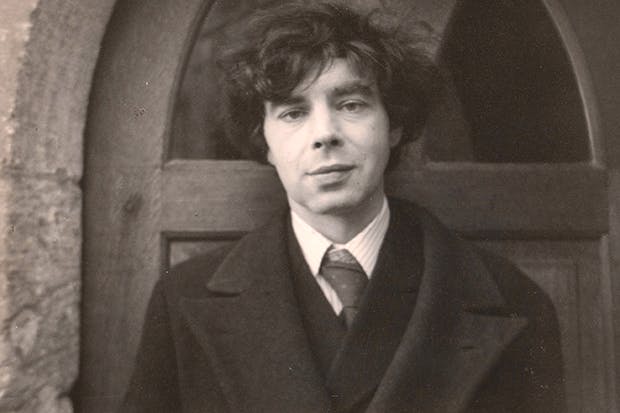

Self-portrait with guitar (c.1952)

Self-portrait with guitar (c.1952)

Writers were always being asked to take a stand on Spain — to take sides — and Lee himself eventually joined the International Brigades. Yet among his patrons were the pro-Franco poet Roy Campbell and his Catholic wife Mary. One of the exasperated men by whom Lee was periodically interrogated told him that according to his reputation among republicans, he wouldn’t know which side to get on a bus.

This is part of what makes him so sympathetic. He’s uninterested in judging, just gets down what people and places and situations are like. His descriptions of a day spent in Toledo with Roy Campbell, or of what it was like, hour by hour, to be in a particular village as civil war broke out, are unforgettable, but still more so are the passages where what he’s recounting is some gratuitous but quickly passed over savagery: the gang murder of a rural intruder, the tormenting of a village idiot (‘After a session of this everyone looked flushed and relaxed’).

What about those similes? In Cider with Rosie there can be a feeling that the older sophisticate can’t resist giving an exotic overlay to his memories. Could the small boy have seen winter fields as resembling oyster shells, or a calf’s mouth a ‘hot, wet orchid’? Much later, when Lee recalls the foot of a soldier crawling in front of him in winter-bound Teruel as ‘bouncing before me like a snowball’, the effect is daft: snowballs don’t bounce.

One can be exasperated, too, given the gap between events and their being written up, that he didn’t bother to try to find out some things — how this place is spelt, how that one was pronounced, or why the quays of Seville stopped functioning. And for today’s sensitivities there are too many episodes in which eager under-age girls squirm into his bed. Yet few writers so unlaboriously — so naturally — communicate the pervasiveness of sex. It was what Lee always cared about most, except alcohol, which he seems to have felt was much the same thing: ‘That pure, almost virginal intoxication, to which all subsequent drinking tries in vain to return.’

A hundred years after his birth, reading him is still sexy, still gently intoxicating.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in