What is worse: Iran with the Bomb or bombing Iran? This is a question we must reconsider as diplomats return to Vienna this week to discuss Iran’s nuclear programme.

Of course, we all hope that the negotiations will result in a lasting diplomatic accord that resolves the Iranian nuclear challenge once and for all. The election of a new and more pragmatic Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, last August and the successful conclusion of an ‘interim’ nuclear pact in November mean that the prospects for a ‘comprehensive’ settlement have never been brighter.

President Obama has called the Iranian nuclear issue ‘one of the leading security challenges of our time’, and a diplomatic bargain that prevents Iran from building nuclear weapons peacefully would be by far the best outcome to this crisis.

Yet we must also be realistic. Obama himself has estimated that the odds of a comprehensive deal are ‘no better than 50/50’. And his former weapons of mass destruction coordinator, Gary Samore, puts the chances closer to zero. Some officials have expressed optimism in recent weeks, but there is still a significant chance that we will fail to get a deal.

Moreover, even a comprehensive bargain might not solve the problem. The final settlement as currently envisioned would leave Iran only six months away from a nuclear breakout capability, severely tempting Tehran’s leaders to tear up the agreement (overtly or in secret) at a later date.

At best, therefore, a final deal will still require the international community to remain forever laser-focused on Iran to quickly detect and respond to any cheating. At worst, it could quickly unravel and the Iranian nuclear clock would resume its countdown.

In other words, it is still more likely than not that diplomacy will not work, and if diplomacy fails to stop Iran’s march to a Bomb, then we need to be prepared for what happens next.

America’s position on this issue couldn’t be clearer. In a series of statements, beginning in March 2012, President Obama has declared that a nuclear-armed Iran ‘cannot be contained’ and he is prepared to do ‘everything required’, including using military force, to keep Tehran from the Bomb.

Make no mistake about it, the Pentagon has the capability to devastate Iran’s nuclear programme. America’s newest bunker-busting bomb, the 30,000 pound ‘massive ordinance penetrator’, would make short work of even Iran’s most deeply buried and hardened nuclear facilities. A US strike would set Iran’s nuclear programme back by a number of years at minimum and create a significant possibility that Iran could never acquire nuclear weapons.

Of course, there are serious risks to a strike, including Iranian military retaliation, and spikes in global oil prices and anti-western sentiment, but foreign policy often involves choosing between bad options and these risks must be compared with those of acquiescing to a nuclear-armed Iran.

Nuclear weapons in Iran would spark a nuclear arms race in the Middle East. Tehran would probably export do-it-yourself atomic bomb kits to other countries around the world. And the global nonproliferation regime would collapse as it became clear that the international community lacked the resolve to stop the spread of the world’s most dangerous weapons.

A nuclear-armed Iran would lead to an even more dangerous Middle East in other ways, too: the Bomb would embolden Tehran to step up its support for terrorists and use its Qods forces to conduct proxy attacks, as well as allowing it to threaten nuclear use in coercive diplomacy against its foes.

Last, but certainly not least, a nuclear-armed Iran could result in Armageddon. Iran’s leaders are not suicidal, but a nuclear Iran will undoubtedly find itself in geopolitical contests with rival states and, in an inherently volatile region with several nuclear-armed states engaging in high-stakes nuclear crises, the risk of something going terribly wrong becomes all too real.

A nuclear war with Iran could very well mean the end of Israel, and once Iran has intercontinental ballistic missiles — something the US defence department reckons could happen next year — a nuclear attack on London or Washington DC.

So it’s clear why there is so much hope for a successful diplomatic outcome. But hope does not guarantee success, which brings us back to our original question.

As a special adviser on Iran policy in the US Office of the Secretary of Defense from 2010 to 2011, I systematically compared these options (deterring and containing a nuclear-armed Iran or conducting a limited military strike on Iran’s key nuclear facilities). In an April 2011 briefing I presented my analysis to top political appointees and military brass in a secure briefing room in the Pentagon.

US defence officials like PowerPoint slides, and the final slide in my presentation was a colour-coded chart showing how the two outcomes under consideration would affect about a dozen key US national security interests. National objectives that improved in a particular scenario were green or neutral yellow, and increased threats to the national security of the country were various shades of orange and red, depending on their severity.

Two patterns stood out. First, there was very little green and a lot of orange and red; these were not good options. Second, the ‘nuclear-armed Iran’ side of the chart was noticeably darker than the ‘military strike’ side, meaning that the risks of a strike paled in comparison to the threats posed by a nuclear-armed Iran. Indeed, at the end of the briefing, the most senior official in the room looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘Well, if you are right, this is a no-brainer.’

President Obama has made a similar calculation. He and former US President George W. Bush do not often see eye to eye, but they agree that a nuclear-armed Iran is ‘unacceptable’.

Still, some question whether President Obama is really willing to use force. After all, he failed to enforce his red lines when the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad gassed his own people and he is currently standing by as Vladimir Putin redraws the map of Europe.

Yet the President’s closest advisers insist that Iran is different. Obama is determined to make worldwide nuclear reductions a central part of his foreign policy legacy, and he understands that a nuclear arms race in the Middle East is deeply antithetical to that vision. As Dennis Ross, formerly Obama’s top Iran adviser at the White House, said, ‘If diplomacy doesn’t work, we have to be prepared to use force, and I think we will be.’

Similarly, Samore has stated that ‘If [the Iranians] move to high enrichment, I think President Obama would have to act. It’s a casus belli. It’s a blatant move. I think that would lead to the use of force.’

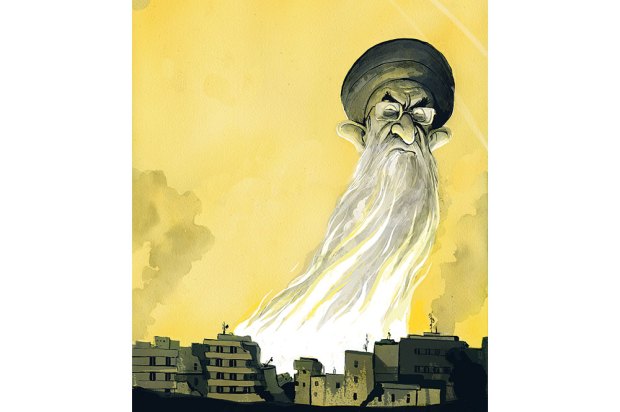

Clarity about our resolve to do whatever it takes might even contribute to a diplomatic settlement. If Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, truly believes the alternative is war with the Great Satan, he might just choose to make a deal with the devil.

Of course, if the time comes, there is always the danger that a leader will go weak in the knees. Or that he will cave to popular resistance at home or abroad. But if the international community truly believes that it is imperative to prevent nuclear war and stop additional countries from acquiring the world’s deadliest weapons, then we must be willing, in principle, to use force to achieve that objective.

If Iran’s nuclear programme continues to advance, therefore, then there may very well come a time to attack. Until then, our thoughts and prayers must be with our diplomats in Vienna.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Matthew Kroenig is associate professor of government at Georgetown and the author of A Time to Attack.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in