The Exploding Galaxy flashed brightly in the black-and-white world that was just coming to an end as I was growing up. When I first met them, my opinion of art was fixed firmly against what I thought of as amateur. I came from a theatrical family, dedicated to extreme professionalism and mockery of anything less. Whether it was holiday pantomimes, school plays or cabaret flamenco — anything short of Yehudi Menuhin and John Gielgud — we would be told how ludicrous they were, how comically inept. It seemed to be the only thing my parents agreed about, and so we went along with it. How we laughed! They would wrap themselves in contempt for less immaculate performers as a form of protection from the rawness of appearing in public.

Professionalism is a counterfeit art. It gets swept away from time to time. Brando did it in the 1950s, Gerald du Maurier in the 1920s, playing one scene with his hands in his pockets. My own allegiance to the dégagé light comedy and perfect timing way of life (which was supposed to be so difficult) was exactly the sort of thing the Sixties in general and The Exploding Galaxy in particular were trying to explode (‘which was rather late for me’).

I came to know them by a series of seemingly random chances. I’d known Guy Brett at school and when I came to London in 1964 I rented a room in his house off the Edgware Road. His brother was at the Architectural Association and one day we all went to a ball there. I had a double ticket but could not find anyone to go with. I asked Hermine to dance and two days later she moved into my room. Guy was the art critic of the Times by now, influenced by David Medalla.

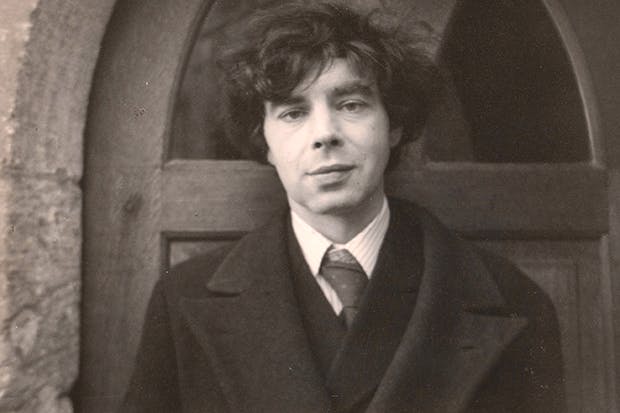

It was the time of Kinetic Art and David was curator of Signals Gallery in Wigmore Street. Art was moving away from my protected world, but Hermine kept after it. Soon after we got married and moved into a house in Islington, Medalla instigated The Exploding Gallery Advance Drama, a commune in nearby Balls Pond Road. They would come round for communal hot baths and snacks, there being no services at No.99. Hermine would go jumble-saling with them, or scrudging (looking for things in the street). It was now that our marriage took a crash course in hippie. Dance dramas were performed at the Roundhouse and Parliament Hill, where we later had annual birthday parties for our daughter, like a kind of ghost tribute to The Galaxy. In those days I was about half way between the thinking of The Galaxy and that of the other inhabitants of Balls Pond Road. Today I feel more sympathetic to what they were trying to do, which was personified for me by the form of Jill Drower [pictured above at the Roundhouse], flitting magically through psychedelic happenings like a dryad of the night.

Every so often a particular kind of professionalism wears itself out and then a cult of inspired amateurishness rises up for a moment and creates innovation through chaos. As Jean Cocteau said, all art is amateur. The Galaxy finally exploded when a Paris heiress started dispensing a large number of francs for them all to go to India. ‘Free money for artistic projects. Please come to 31 Rue de l’Echaude. Telephone…’ ran the ad in the Herald Tribune in 1968. Hermine was included in the gold rush. In order to be different she took our three-year-old daughter all over South America. But that’s another story.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

The above is a foreword to 99 Balls Pond Road: The Story of The Exploding Galaxy (Scrudge Books, £59, pp. 522, ISBN 9780992777500). Available through scrudgebooks.com

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in