My father died a few months ago. That was obviously a sad event for my family. However it marked the beginning of an interesting detective story that has proved quite a delight and has bizarrely taught me some things about the history of liberalism along the way. And being a Liberal party member of the federal parliament I find the coincidence that I will reveal below quite exciting.

My father was in his mid-eighties and definitely in his declining years. As one of his friends said to me at the funeral, he must have done something right in his years on earth to be blessed with a quiet death at his home, sitting in his favourite armchair waiting for a morning cup of tea. One of the things I had been pestering him about over the last few years was for him to dig out of the back of the cupboard some family history research I knew he had but had never had a chance to read in detail. His passing gave me access to those recesses of the house that filial respect forbade me wandering through before then. So I found the research documents.

They are not about my father’s family — the Hendys — who come from Cornwall in England, but of the family of my mother. She passed away herself a few years ago. My mother’s family are the Hardys and they too are from England — spanning the length from the south coast to Westmoreland and the Lake District. The family tree I was looking for recorded the lineage of the Hardy family back to 1571. But the reason I am writing this article relates to just one of those ancestors. In fact she was the niece of my five-times-great-grandfather. Her name was Harriet Hardy. That is not a name I would guess any reader would recognise.

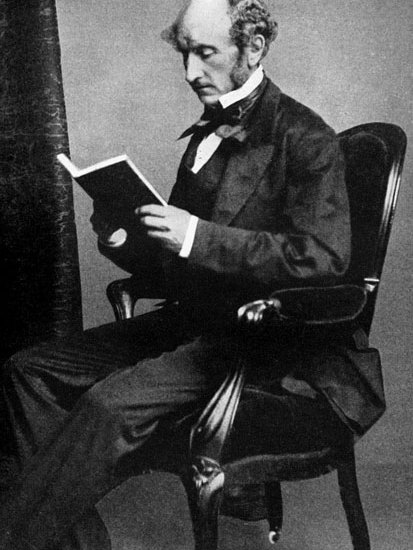

When I note that she was the wife of John Stuart Mill, one of the fathers of English or classical liberalism, my guess is that I am starting to get your attention. As the Dictionary of Liberal Biography states, Mill ‘is one of the most famous figures in the pantheon of Liberal theorists, and the greatest of the Victorian thinkers’.

The documents from the back of the cupboard didn’t record this marriage but some additional research I undertook myself tracked her connections down. My family has a direct link to the Hardy family that left Birksgate in Yorkshire and became substantial landholders in South Australia, building Mount Lofty House among other things. The man who did that was Arthur Hardy, the younger brother of Harriet. He was a member of Colonel William Light’s original surveying team to the colony and settled there permanently. In his diaries he wrote often about his favourite older sister and his overseas visits to the Mill household and other excursions to see the poet Wordsworth among other notables. I understand that in his diaries Arthur ‘accepted that Harriet’s influence upon Mill had been great, and even said that she practically wrote the book On Liberty herself.’

When I read that I of course said, ‘No, you can’t be serious.’ Recently Andrew Norton wrote that On Liberty ‘marked a turning-point. It gives “individuality” priority over other ways of life, and sees society, as much as the state, as the main threat to freedom… On Liberty reads more powerfully today as an argument against state intervention… [it] survives as not just a classic, but as a still-read classic.’

So how influential was Harriet on Mill’s works, and who was she?

Harriet is actually better known to posterity as Harriet Taylor. When still young she married a druggist, John Taylor. She had a semi-scandalous relationship (although many academics think it may have been purely platonic) with Mill from around 1830 until Taylor died in 1849. Not long after Mill and Harriet married and stayed together until her death in 1858.

It is Mill himself who attributes joint authorship of On Liberty and also of his other great work the Principles of Political Economy to Harriet.

In his preface to On Liberty he famously wrote: ‘To the beloved and deplored memory of her who was the inspirer, and in part the author, of all that is best in my writings… Like all that I have written for many years, it belongs as much to her as to me; but the work as it stands has had, in a very insufficient degree, the inestimable advantage of her revision.’ For Political Economy he also stated that part of the book on the proper conditions of the labouring classes ‘was wholly an exposition of her thoughts, often in words taken from her own lips.’

Further he stated: ‘The writings which result are the joint product of both, and it must often be impossible to disentangle their respective parts, and affirm that this belongs to one and that to the other. In this wide sense, not only during the years of our married life, but during many of the years of confidential friendship which preceded it, all my published writing were as much my wife’s work as mine.’ There is much more in this vein.

Much academic perspiration has gone into deciphering these statements. Understandably there is a deal of scepticism about the veracity of these emotionally charged passages about an obviously greatly loved partner.

J.E. Jacobs has declared that it is clear that at least one chapter of Political Economy was ‘written primarily by Taylor Mill’. In contrast William Barber stated that her influence on On Liberty and Political Economy was ‘understandably, exaggerated’. And Dale Miller concluded after a lengthy discourse that the available evidence was ‘too sparse and too contradictory for this challenge to be surmountable’ although Harriet certainly heavily influenced his other work The Subjection of Women. Other scholars such as Laura Ross, W.L. Courtney, Alan Ryan and Bruce Mazlich have similarly reviewed the issue with some dismissiveness while others are unable to be completely definitive either way.

We will never know for sure Harriet’s true influence on liberalism. I for one am willing to claim that my ancestor is one of the mothers of classical liberalism and political economy. It also happily establishes a direct link between the liberal writers of 19th-century England and the Australia of then and now.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Peter Hendy, a former chief executive of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, is a Liberal MP for the federal seat of Eden-Monaro.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in