In his essay on the ‘Peculiarities of the English’, E.P. Thompson gave his theoretical definition of class:

When we speak of a class we are thinking of a very loosely defined body of people who share the same congeries of interests, social experiences, traditions and value-system, who have a disposition to behave as a class, to define themselves in their actions and in their consciousness in relation to other groups of people in class ways. But class itself is not a thing, it is a happening.

Selina Todd has a snappier and more prosaic definition of the working class (‘The People’) as ‘a class of workers who depended on earning a living and were in that way distinguished from the rich who lived on the labour of others’.

Whether it’s more of a thing or a happening, Todd sets out to record its history from 80 years after Thompson’s seminal work, The Making of the English Working Class, ends.

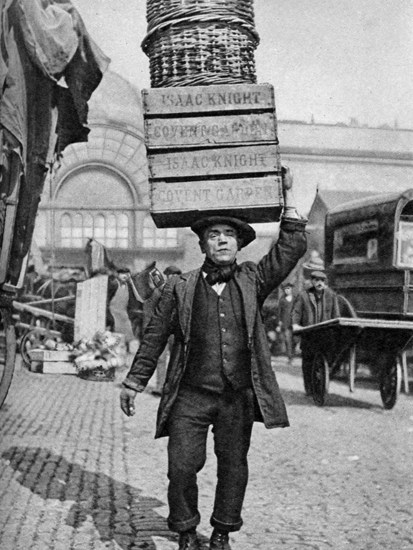

She seeks to describe the unmaking as well as the making, for her contention is that the working class is on the slide, its best days behind it. The period chosen for her study is not as random as it may seem. It revolves around servitude and the franchise. In 1910 there were almost two and a half million servants. Within ten years this had reduced by a million; strident voices from the bourgeoisie were already bemoaning the loss of deference.

In the 1910 election only the 7.7 million men with sufficient property were allowed to vote. By 1929 (the first election under universal suffrage) there were 32 million voters. The Daily Mail (that reliable foghorn against the dangers of social progress) was warning of ‘the flapper vote folly’, arguing that giving young women the vote would take the country backwards.

Todd is excellent in describing the effects that the Great War had on society and her use of servants as barometers of social change brings a fresh voice to this history. She also reminds us that ‘the persistent assumption made by the powerful and privileged that the wilful idleness of the poor caused poverty’ has a long pedigree.

If the first world war brought emancipation, it was the second that heralded the New Jerusalem. Unfortunately, it’s at this stage that the author begins to indulge her Wolfie Smith theory of social history — the one where the noble worker is constantly betrayed by his leaders.

Attlee’s government may well have created the NHS, nationalised the mines and the railways, implemented Beveridge and begun a huge programme of house-building but its policies ‘constrained working-class people’s power in ways that provoked frustration’. Here’s what those bastards did. They ‘maintained private housing’ and ‘differential wage rates’. It’s a wonder anyone was foolish enough to vote for them.

As for the trade union movement, ‘Workers found that their union officials were granted a seat at the negotiating table, where they frequently became management’s spokesmen.’ We soon learn where Todd’s sympathies lie. Not with the poor sods who spent a lifetime in the service of their fellow workers, negotiating decent pension schemes, improving pay and conditions, constructing disciplinary codes that protected workers against arbitrary dismissal. No — these class traitors were actually sitting down with managers, disgracefully engaging in free collective bargaining.

The real heroes according to this account were those who didn’t bother with the tiresome process of being elected to represent anyone. Men like the self-confessed Beatnik Teddy Boy who Todd introduces us to in breathless admiration. Beatnik Boy wanted unions to fight for ‘the opportunities for creativity, self-expression and participation in everyday working lives’.

As I read this I could hear the rallying cry:

‘What do we want?’

‘The opportunities for creativity, self-expression and participation in everyday working lives.’

‘When do we want it?’

‘Now!’

Todd writes well on education, a subject she is more familiar with. She reminds readers that while the Butler reforms were a vast improvement on what went before, ‘norm referencing’ preserved higher education for a tiny elite. While around a quarter of students qualified for a university place, only 4 per cent actually went. She also points out that grammar schools meant that the majority of children, in the words of the 1959 government-commissioned Crowther Report, were ‘condemned to an abbreviated schooling’.

Constrained by her political prejudices, Todd speaks eloquently of the need for workers to have more control over their working lives but says nothing of the various attempts at industrial democracy in the 1970s or the failure of the British trade union movement to follow the same route as their European brothers and sisters.

She and her Dave Spart contributors bemoan the plight of the working class from 1966 onwards, describing them as ‘the dispossesed’. The legalisation of homosexuality, the decriminalisation of abortion, the race relations and equal pay acts are recognised as important advances, ‘but they indicated the government’s intention that economic and political rights should be attached to individuals rather than to groups’. No they didn’t. They indicated that it was wrong to discriminate against people because of their colour or their sexual orientation. They indicated that we should stop driving working-class girls into the embrace of the back-street abortionist.

There is much in this book’s analysis of where the worship of market forces has taken us, and the author is right to warn of the dangers of an unequal society. But Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett’s 2009 The Spirit Level said it better, and David Kynaston generally offers a more enlightening social history of the postwar years.

I don’t accept that the working classes have suffered a fall; but I do accept that they’ve been a huge disappointment to people like Selina Todd and her friends.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20.00, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in