Who is Dmitry Firtash? Can he solve Ukraine’s troubles? And why is he currently under effective house arrest in Vienna, awaiting extradition on corruption charges to the US, with his bail set at a whopping €125 million?

None of these questions has a simple answer — and when I fly to Austria to meet him it’s not even clear if I’m going to ask him. Firtash appears to be up for it, as far as can be ascertained via his barrage of minders, advisers, security and hangers-on. But his expensive American lawyers most definitely aren’t. It might jeopardise his case, they’re saying. Firtash mustn’t say a word about anything.

‘Who do they fucking think they are?’ says one of Firtash’s PRs. ‘I hate American lawyers,’ says another, from a different agency. (Firtash has three different firms representing him: a) because so much is at stake, and b) because, being worth several billion, he can afford it.) The wrangling goes on into the night and through most of the next morning. Besides American lawyers to contend with, there’s also a Rosa Klebb-like minder and several trusted business associates, each with firm and contradictory views on exactly what Firtash must and mustn’t do to better his cause.

While we’re waiting for them to decide, let me tell you why I’m interested. Dmitry Firtash is the Keyser Söze of Ukrainian politics — a mystery figure about whom you hear two very different stories. According to one version, he’s a benign self-made businessman who gives generously to charities around the world, with the power — perhaps greater than any other Ukrainian citizen — to steer his troubled country towards stability and prosperity.

According to the other, completely unproven version, which he denies, he’s Putin’s bagman, another of those crooked oligarchs who made their money through dirty means — and is now about to get his just deserts at the hands of the US legal system, which has the power to extradite him, imprison him and seize his billions.

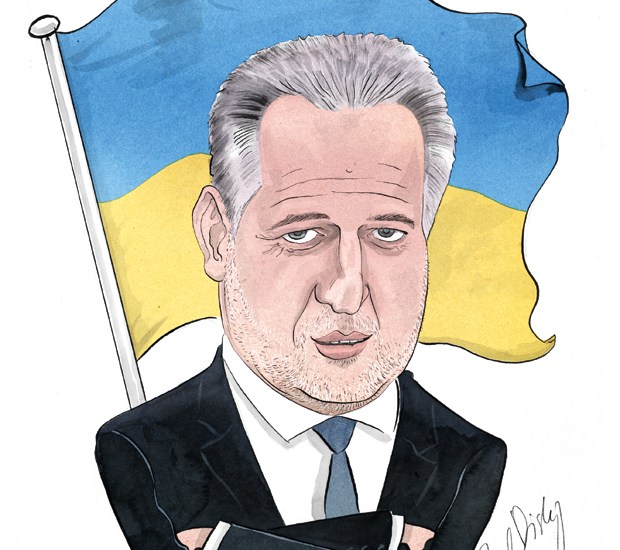

Now’s our chance to find out, for here he is, finally, in a chair in front of me. He’s 48 and has watchful grey-blue eyes, a beaky broken nose, a close-cropped beard and the air of a man very used to being obeyed. He’s polite, even allowing himself a quick, sweet smile at times, but intimidating. When, for example, his young translator fails to make the grade, the speed with which he is ejected from the room and replaced is terrifying. If he doesn’t like your questions — he irritably batted away my first one, when I tried to get him to sum up, as simply as possible, the political situation in Ukraine — he lets you know. But once he has warmed up he’s unstoppable.

The question that gets him going is when I call him an oligarch — a term he loathes because ‘it belongs to the Nineties, to the era of perestroika’. He launches into a long, involved story which takes in much of his early life and outlines his personal business philosophy. ‘You make up your mind whether I’m an oligarch or not,’ he says with a watchful stare.

Firtash’s story begins in May 1965, when he’s born in the Ukrainian village of Sinkov, of humble parentage — father is a driving instructor, mother is an accountant. Because Ukraine is part of the Soviet Union, Firtash has low expectations for his future — study at Krasnolimansk Railway Vocational School, compulsory military service, then a degree from the National Academy of Internal Affairs in Ukraine, end up as a train driver.

Though he says he never intended to be rich, he clearly had drive and a rebellious streak. He tells how at 18, having landed a place at a college which might have postponed his military service, he spotted a girl he fancied in one of the all-women accommodation blocks. ‘I wasn’t pretty, but I was quick,’ he says. So he arranged a secret assignation in her fifth-floor room.

In the dead of night, he clambered perilously up the concrete balconies and stole into his inamorata’s bedroom. ‘I wasn’t wearing much and I didn’t mess about. I hopped straight into bed with her — but instead of finding something warm, young and tender, I found something larger and older. There was a loud scream.’ Firtash had accidentally got into bed with one of the senior course tutors. The next day, he was expelled, on the train and off to military service.

Like so many entrepreneurs of the era, Firtash made his fortune by cannily exploiting the instability and chaos which followed the Soviet collapse — in his case by acting as the middle man trading Ukrainian food supplies for Central Asian gas. ‘Where Moscow had once made the decisions, now we were on our own,’ he says. ‘None of us knew what we were doing, but we were learning really fast. By then I had a wife and daughter to take care of and my priorities shifted. Now I had to make money.’

This was something for which Firtash clearly had a natural aptitude. He is now one of the biggest players in the Central and Eastern European chemical and energy industry, with plants in Ukraine, Germany, Italy, Cyprus, Tajikistan, Switzerland, Hungary, Austria and Estonia. His companies employ more than 100,000 people, with an annual turnover in 2012 of $6 billion.

What’s his secret? ‘I work very hard — 16- or 17-hour days — with very few weekends off and only see my children on vacations.’ But the other factor in his success, he believes, is his enlightened approach to business, combining the capitalism of the West with the social conscience he learned as a worker in the days of the Soviet Union. ‘If you want people to work well for you, you have to look after them.’

Now you could argue that this is the sort of thing an oligarch would say. (You might also be cynical about the $230 million he has donated in the past three years to charity, such as a scholarship endowment at Cambridge and the Holodomor memorial in Washington.) But it would be a brave man who doubted the burning sincerity of Firtash’s commitment to his homeland: unusually among oligarchs, his children are all educated in the Ukraine, and his money — again much to the concern of his London financial advisers — is in one basket at home, not abroad.

Which is what’s so puzzling about this US extradition attempt: if it really is being done for geopolitical reasons — as many, including Firtash himself, suspect — it could scarcely be more counterproductive. What Ukraine needs is leadership: Firtash, though he has no political ambitions himself (‘yet’, he says), is respected across the country as an employer, a strategist and fixer, with sufficient cachet in both the pro-Russian and Maidan-nationalist camps to hammer out the kind of deal that might offer Ukraine an independent, even prosperous, future.

Among the things that Firtash would like to do — and was doing until his arrest, on the orders of the Americans, in Vienna — is secure Ukraine’s energy independence. In 2006, he negotiated a nifty deal whereby Ukraine could keep its energy costs down by importing some of its gas cheaply from Turkmenistan. Gazprom was cut into the arrangement, so the Russians were happy. But all his good work was undone by his arch-enemy, President Yulia Tymoshenko, who cancelled Firtash’s contract and replaced it with one more favourable to Putin. The result was that the gas price in Ukraine more than doubled, and Ukraine now finds itself the helpless — and indebted (it owes Gazprom $2.2 billion) — victim of Russian energy blackmail.

‘The superpowers don’t care about Ukraine, they just want to use it as a battleground,’ says Firtash. ‘For them it’s just a dot on a map, but for me it is the map. Because of its geographical position, obviously it will always have to look both East and West, but its future belongs with neither. We are an independent country with our flag and we should be able to forge our own destiny.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in