Eschewing the biblical advertising of ‘the promised land’ or indeed ‘a land of milk and honey’, the Conservative colonial secretary William Ormsby-Gore presented a far grislier picture of Palestine on the eve of the second world war when he described it as ‘full of arms and bitterness, and there are few who do good and many that do evil’. That précis is proved sadly accurate many times over in Patrick Bishop’s gripping The Reckoning, about the fatal shooting and subsequent martyrdom of the Zionist freedom fighter (or terrorist — take your pick), Avraham Stern.

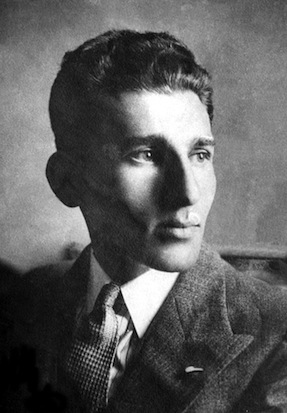

As characters go Stern is compelling in a car-crash kind of way. Bishop — a former Middle East correspondent for the Telegraph who now writes engrossing 20th-century histories — sums him up quite marvellously as ‘a dandy aesthete with visions of sacrificial violence’.

Born in Suwalki, Poland, on 23 December 1907, Stern’s comfortable upbringing as the son of a surgeon was thrown into chaos when his home town fell to the Germans in 1915. For the next six years he lived more or less as a refugee beyond the control of adults. Highly intelligent and an accomplished poet, he was also ‘a show-off, with a compulsion to perform’. When the family eventually reunited, Stern’s Zionist parents decided to send him to Jerusalem to finish his studies. After landing in Palestine on New Year’s Day 1926, Stern gradually grew more radical politically, to the point where he joined the Irgun, a Zionist paramilitary group, in 1932. In August 1940 he founded his own breakaway militant group, Lehi, which the British colonial authorities in Palestine dubbed the ‘Stern Gang’.

Like a good detective novel, Bishop’s account begins with Stern’s shooting in a Tel Aviv apartment on 12 February 1942, and works its way, Rashomon-like, back through the events which led up to the fateful day. Most of all we get to learn about Stern’s killer, a certain Geoffrey Morton — who died in 1996 — star detective of the Palestinian police, who, despite evidence to the contrary, held Stern responsible for the death of a close friend.

It is here that Bishop falls down. Though he has talked to Morton’s daughter, and has made use of a wealth of information (including an autobiography the policeman published in 1957 and another memoir, finished in 1993), he cannot make Stern’s nemesis vivid. Whereas Stern himself is rendered flesh-and-blood by numerous telling details (his inclination for silk socks, for instance, or how on the run he carried around a large suitcase containing a collapsible bed), we are told that Morton was a music-lover — but what sort of music the devil knows. Even when we learn something seemingly important about him he remains as enigmatic as a matinée cowboy wearing a white hat: ‘Some people seem to think that I was anti-Semitic, and others that I was anti-Arab,’ Morton pronounced. ‘I wasn’t. I was merely anti-terrorist, whether they were Arab or Jew.’

This is unsatisfactory because at the heart of this true detective story is the question of whether Morton lied or not. Did he or did he not shoot an unarmed Stern in cold blood? Morton maintained, for the rest of his life that he shot Stern dead because the latter had tried to escape through a window and might have triggered an ‘infernal device’ that would blow everybody in the room up.

This version of events was called into question several times in subsequent years. The most damaging testimony came from a fellow policeman, Sergeant Bernard Stamp, who claimed to have been in the room when the shooting took place. According to Bishop, in a statement Morton gave immediately after the event, he acknowledged Stamp’s presence, but years later he denied the sergeant had ever been there. Not long before he died, Stamp said that Morton shot Stern without him having made any attempt to escape, and that any talk of there being an ‘infernal device’ was trumped up nonsense.

‘Rarely can a single act have produced so many different versions of events,’ writes Bishop. Whatever the truth of the matter — and it is fair to say that Morton is not made to look very good — Bishop is quite right in concluding that Avraham Stern (or Yair as he came to call himself, in homage to Elezer ben Yair, one of the leaders of the Jews of Masada) turned out to be more dangerous dead than alive:

In death, he achieved the status of prophet and martyr he had yearned for when alive, and his spiritual presence shaped events in a way that his physical one could never have. Yair’s analysis — that British defeat was essential if the Jews were to have a state — became the prevailing wisdom.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in