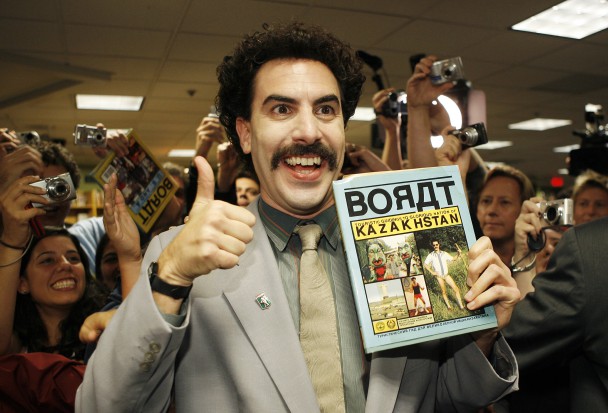

The scene: a redneck bar in Tuscon, Arizona. Sacha Baron Cohen, under the pseudonym of ‘Arote and his Cowboy Astana Band from Kazakhstan’, takes to the stage to perform a country and western song about ‘the problems in my country’. The first verse mentions the poor roads, with Baron Cohen singing an odd refrain: ‘throw the transport down the well.’ The crowd look unimpressed.

It’s the next verse that wakes them up, as a list of grievances against Jews ends in the repeated refrain, which the crowd quickly warm to, of ‘throw the Jew down the well.’ The performance, available on YouTube, is a savage indictment of anti-Semitism. It is also breathtakingly anti-Semitic.

Are some subjects too absurd to be satirised?

Once, I was hoping to satirise an exchange on Q&A between Richard Dawkins and George Pell, which included such gems as ‘Probably no people in history have been punished the way the Germans were’ and ‘For some extraordinary reason God chose the Jews. They weren’t intellectually or morally the equal of the Egyptians or the Persians. The poor little Jewish people, they were shepherds.’ I gave up, edited a transcript of the whole thing and stuck a comment at the end: ‘some conversations defy satire.’

Yet people who read it (and hadn’t seen the show) presumed I’d made the whole thing up. I was stumped. What do you do when reality is more bizarre and more illogical than satire?

In America, we learn, a staggering one in four people surveyed don’t know the earth revolves around the sun. An American daytime TV show presenter can’t say whether the earth is flat or not. A rattlesnake preacher gets killed by his own rattlesnakes. Try and satirise that.

In the last few months I’ve written twice on Sydney University’s flirtations with anti-Semitism. The first poked fun at the absurdity of Jake Lynch and his Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, the second on Tim Anderson’s schmoozing up to Bashar al-Assad. My attempts to satirise them included lines such as ‘Learn how vile Zionist bankers and evil chocolate retailers drank the blood of babies whilst plotting the Global Financial Crisis!’ The response was not entirely what I expected.

‘Disappointed in your column today. Funny at first but then it descended into an anti-Israel rant. Not your usual style regrettably’ wrote one regular reader.

I was devastated. I reread my piece, checking to make sure I had indeed planted enough clues that this was satire, and not literal comment. I’d even mentioned a (fictional) Professor Goebbels.

I replied that I hoped I was highlighting the ‘absurdity of anti-Semitism’. My reader kindly reread the piece and agreed. Then made this insightful comment: ‘even if things are absurd, if they get repeated often enough they become fact.’

To poke fun at the absurd, you have to go beyond it. Yet no matter how much comical hyperbole you use to prove you are joking, it’s difficult to be more absurd than the real thing. Maybe it’s impossible.

In his movie Borat, Baron Cohen did a spoof called ‘the Running of the Jew’ with a Jewish caricature being hounded down the street. But if you hadn’t heard of the Running of the Bulls — as many of his young teens audience wouldn’t have — this piece ceased to be satire. It became, horrifyingly, it’s own piece of anti-Semitism.

To mock is to disempower. Humour allows us to challenge entrenched bigotry, prejudice, stupidity and so on. The famous Jewish sense of humour was a way to retain sanity in the face of the horrors of the holocaust and the treatment of Jews in European history.

Mel Brooks’s finest piece of satire is The Producers; where Springtime for Hitler, designed to be a flop, is a surprise hit. In the Seventies the audience accepted the premise that Hitler is the all-time baddie, so the joke’s funny. But if you came up with that idea today, and put it on in some fringe theatre, I bet you’d end up attracting a very different and very ugly audience.

One of John Cleese’s funniest scenes is the ‘Don’t Mention the War’ sketch in which a German family turns up at Fawlty Towers and Basil can’t help goose-stepping around the place with his finger under his nose, trying not to salute. Monty Python did similar sketches. Looking at them now, the gestures aren’t that far removed from the repulsive ‘quenelle’ salute that is being touted by one particularly unfunny comedian in Paris, the repellent convicted anti-Semite Dieudonné M’bala M’bala.

Dieudonné specialises in what can only be called Holocaust humour. His song ‘Chaud Ananas’ (hot pineapples) is a French wordplay on ‘Shoah nanas’ (holocaust loose women). The lyrics are a repugnant sludge of obscenity, sexuality and, er, the holocaust. When Monty Python mimicked Nazi behaviour, it was harmless schoolboy humour. Now the same stuff is used by the far Right, dressed up as comedy.

With the relative moralism and double standards of so-called progressive thinking, our kids are taught that there are no ‘baddies’; every villain’s point of view has some kind of validity. When the accepted creed is that one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter, there’s a lack of basic, shared truths and certainties. Thus, the ironic component of humour has nothing to grip onto.

Whilst it’s hugely offensive to use the N word under any circumstances (unless you’re black), anyone can fling the J word around with abandon. Go to any Sydney dinner party, and once the grog is flowing you’ll be astonished how casually and passionately otherwise sane individuals will vilify Jews (often, but by no means always, under the guise of being ‘anti-Israeli’).

Throw in the internet where revolting lies and falsehoods are presented as fact and we have a new creed: one man’s lie is another man’s truth.

What happens when accepted wisdoms and conventions, the anchor for humour and irony, have evaporated? Is my reader right; do absurdities repeated often enough simply become fact?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in