When Richard Mabey was researching this biography of Flora Thompson, author of Lark Rise to Candleford, he happened to stay at a farmhouse B&B near Bath. Ambling around, he found

something very curious … There were two rows of cottages facing each other, with a dusty track between them …There were clean curtains in the windows. The gardens were in good order, with sweet peas in flower and rows of fat cabbages. It was a vision of an English village as idyllic as a Helen Allingham painting … I edged round the back and realised they were two dimensional … a façade but nothing behind.

The next day the farmer’s wife explained that this was one of the sets for the BBC production of Lark Rise to Candleford — a long way from the Oxfordshire, where the book was set and where Flora Timms (as she then was) grew up, but ‘much closer to the rural dream’.

Well, you can see where this is going as metaphor, can’t you? The idyllic façade, removed from the reality of rural squalor? And Mabey duly drives his point home:

Had Flora Thompson been as adept with her paint spray as the designer, creating an artful two-dimensional deception that has continually bewitched us because it is what we expect to keep our dream alive?

This, then, is the premise — I might say, the straw doll — that the author sets up to give Dreams of the Good Life a polemical basis: did Flora Thompson give her celebrated account of rural life in the 1880s a retrospective spin when she wrote it as a woman in her sixties on the cusp of and during the second world war? Others have made the same point; the academic Barbara English has suggested that

she constructed a past which never really existed … Lark Rise resembles those memories of childhood where the sun shone all summer, and there was always snow at Christmas.

Well, you know, in some childhoods (Dickens’s, for instance) there really was snow at Christmas. And the notion that Flora Thompson (born in 1876) was giving the hamlet of her childhood a retrospective gloss doesn’t survive even a cursory reading of her trilogy, Lark Rise to Candleford, especially the first and best part, the description of the hamlet she called Lark Rise. There’s nothing glossy about her bleak account of the reality of making do on wages of ten shillings a week, or indeed about a (delicately worded) reference to coitus interruptus as a contraceptive method.

Actually, Mabey doesn’t really have much time for the notion of Flora as a fantasist. As he says, you trust her account.

Flora … gazes about like an indigenous anthropologist, missing nothing, but always slightly on the outside of things … there are smaller vignettes of farming life, whose precise and intimate detailing is more revealing and carries greater conviction, than any literary equivalent of landscape painting could.

As for the details of domestic life she describes,

there is always the possibility she is fictionalising some of this material, but it has a persuasive sense of detail, of ‘inside knowledge’ that makes you trust her.

I’d go further. This is the kind of social history only a woman could write; or rather, the grown-up version of an intelligent, observant girl.

The poverty of the cottagers in Lark Rise has the backdrop of the Enclosure Acts; one old lady recalled her father making a good living for his family from their long-gone access to common land. From her later experience as a post office clerk Flora could describe how those old people’s lives were transformed by the advent of the old age pension:

They were suddenly rich. At first when they went to the post office to draw it tears of gratitude would run down the cheeks of some…and there were flowers from their gardens and apples from their trees for the girl who merely handed them the money.

What was it about Flora that made her such an acute observer? Crucially, she was a bit of an outsider. Her parents were a cut above their neighbours; her father was a skilled stonemason rather than a farm labourer. Her mother had worked for a clergyman and his family.

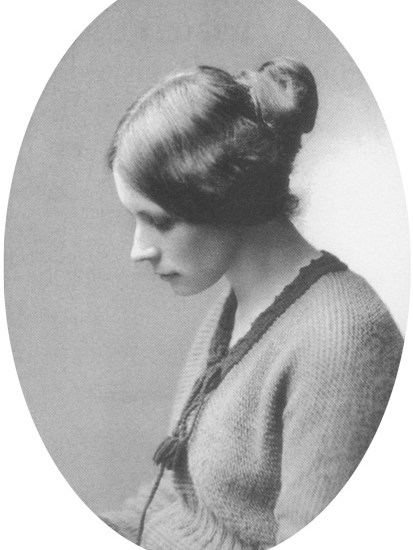

The other important thing was that she wasn’t, by the standards of the time, a looker, though photographs show a perfectly attractive brunette. Her mother was pretty and Flora was a disappointment by the one criterion that mattered. She was the perennial second fiddle, the slightly plain, under-educated but intelligent girl onlooker; and as such she became the ecologist, the naturalist, of her own environment.

This book is as good a defence of Flora Thompson as you’ll get. But as biography it encounters exactly the same problems as its predecessors, which is that this very private woman left not much in the way of information about her life other than the pointers in her work, notably her underrated account of her time as a post-office assistant in Hampshire, Heatherley.

Anyone reading Lark Rise — and if you haven’t done so, let me get right down on my bended knees and implore you to give it a go — will be curious about the author. What about her siblings, other than her beloved brother Edwin, some of whom died in childhood? What was her husband like? (A sergeant-major type, according to one friend, though Mabey is kinder about him than most.) You don’t get much more here than you do from the books, which are unconsciously revelatory about her romantic disappointments, and from the essay written by Margaret Lane in the introduction to her (very good) selection of Thompson’s work, published in 1979.

The trouble about Flora Thompson and Lark Rise, as Mabey suggests, is that she originally intended it as a novel but Oxford University Press, her publishers, didn’t then do fiction so it was billed as autobiography. Which of course it was, but the fiction of it being fiction did at least allow her a bit of licence, to compound characters, say. This isn’t a problem for the reader, but it does mean that nerdy biographers get the opportunity to catch her out in discrepancies; even Mabey goes in for it.

The other, bigger problem is not so much in Thompson’s works but their presentation. Mabey observes that editions of the book haven’t served the author well (he’s unduly harsh on H.J. Massingham, who wrote the original, highly influential introduction). One version of Lark Rise was lavishly illustrated: a savage passage about the eviction of an old major was undermined on the opposite page by an idyllic cottage scene by Helen Allingham. It sums up the misrepresentation of Flora Thompson.

As for the notion that she fell victim to the folklore cult of the time, she sent it up in one account of her childhood May Day celebrations, which were ruthlessly reinvented, she said, by a visiting aesthete:

Our crude rejoicings did not satisfy his fastidious taste; he found our customs staled and debased from the handing down of many generations and attempted a revival of Merrie England.

She observed her human environment as she did nature: closely, wonderingly, compassionately. Small wonder Richard Mabey, a fine naturalist himself, likes her.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £13.99. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in