In Tórshavn, capital of the Faroe Islands, I met a man who first helped his father kill a whale with a sharp knife when he was eight years old. The spouting blood soaked his hair and covered his face like warpaint. He remembered the warmth on his skin, a contrast to the cold North Atlantic in which they stood.

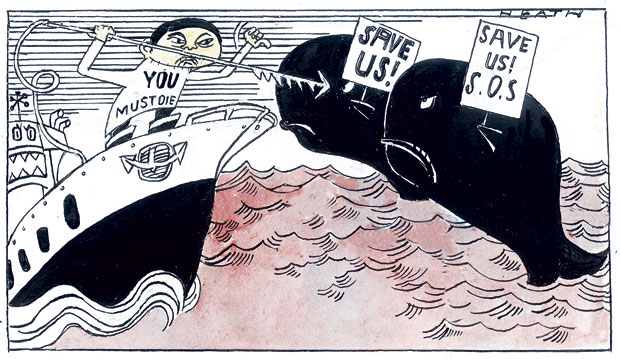

These days we assume that people who kill whales and dolphins must be bad. Flipper and his cousins are our friends, and notwithstanding that unfortunate business with Moby-Dick, those who pursue whales for their flesh must be terrible human beings. We know now, as Herman Melville did not, that cetaceans are exceptional mammals, highly intelligent with elaborate social networks and close family relationships. They are capable of exhibiting grief and even of coming to the aid of human beings in distress.

In several parts of the world, there are moves to give these special animals legal protection as ‘non-human persons’. India passed that law late last year, and in 2011 the American Association for the Advancement of Science began gathering support for the Declaration of Rights for Cetaceans. The first article in that declaration is: ‘Every individual cetacean has the right to life.’

In a week or two, environmental campaigners from Sea Shepherd will be touring Britain enlisting public support to end what they call the ‘barbaric and merciless slaughter of whales and dolphins in the Faroe Islands’. The campaign is gathering rapid traction on social media, and video clips of the Faroese hunt (known as the grindadráp) have been ‘liked’ and circulated in their hundreds of thousands. In those clips, the sea is stained red, the flapping pilot whales are dragged ashore with ropes and grappling hooks, and they are killed with a sharp instrument that severs the spine close to the head, resulting in almost instantaneous death.

Sea Shepherd compares the Faroese whale hunt with the Japanese dolphin slaughter at Taiji, an annual process where hundreds of dolphins are herded into a small rocky cove. Babies and young adults are then separated from their mothers for sale to Chinese theme parks, and the others are stabbed to death by fishermen from above with flensing knives attached to bamboo poles. It is an awful scene of prolonged carnage. And, as we know, Japan has been utterly unwilling to countenance restrictions on its annual so-called ‘scientific whaling’ expeditions.

I respect the bravery with which Sea Shepherd confronts the Japanese whaling ships in the South Atlantic. And I applaud Blackfish, the recent documentary shining a spotlight on the highly dubious practice of exhibiting orcas for family entertainment at Seaworld in the USA. I’ve never killed a whale. And I think I could not do it. But I am uneasy about the campaign to target the Faroese and I’d defend the right of that father and his young son to hunt and kill whales. Theirs is a dramatic land, a green and treeless collection of 18 islands in the North Sea where just 50,000 people still live a life intimately connected to the elements. They have traditionally eaten puffins, great skuas, storm petrels and fulmars. Along the sharp sheer cliff edges there are wooden stakes embedded in the ground to which hardy islanders attach a rope and dangle perilously to catch birds on the wing, or gather eggs from nests on the rock face.

Historically, the islanders have relied on whale meat as an essential part of their survival. These are fiercely independent people, intimately connected to their natural environment in spite of modern heating, air links (when the clouds clear for long enough) and the internet.

They have never set out to look for pilot whales: they kill them only when a school is discovered close to shore, and only if one of a small number of designated beaches is near enough to use as a landing ground. According to the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Conservation Organisation, pilot whales number more than 750,000, and each year the slaughter is estimated to take less than 0.1 per cent of the population. Records have been kept since 1584 — which makes this the longest recorded tradition of any human-animal interaction. Experts think the practice has been going on for more than 1,200 years.

The grindadráp (whale hunt) is not merely something from the Faroese past. It is a reminder of their relationship to the sea, and the meat is still a favourite delicacy.

Wouldn’t it be better if high-profile marine campaigns left the Faroese alone and focused on the more immediate and pressing threats to ocean ecosystems? Only this week a factory was discovered in Pu Qi in China that is processing more than 600 whale sharks a year. The world’s largest fish, a harmless plankton feeder, is known to be dwindling fast across the tropics. In the Mediterranean, a combination of vested interests (some criminal) and lax European Union laws have resulted in the decimation of tuna populations. In the St Lawrence River in Canada, a small population of beluga whales is being poisoned by PCBs. Around 100 million sharks of all species are being caught worldwide to feed the Asian market for sharkfin soup. In many areas, 90 per cent of large carnivorous sharks have been removed from the ecosystem. In India and Sri Lanka, there is a burgeoning fishery for giant manta ray gills to make ‘blood purifiers’ for the Chinese medicine trade. Parrotfish and conch are being overfished in the Caribbean, allowing algae to lay waste to the coral reefs. The list could go on and on and on.

Endangered fish species are commonly found on most British restaurant tables and, due to overfishing, our once superabundant cod populations continue to show little sign of recovery. These are the marine issues that I worry about. There is one ocean on our planet, not six or seven or more according to labels on a chart. All that sea is connected to form a giant system that we have neglected and continue to plunder. Let’s not victimise one tiny human population who are carrying on a tradition that will in all probability die out naturally in time. For now, let them eat whales.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Tim Ecott is the author of Neutral Buoyancy: Adventures in a Liquid World.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in