A decade ago if you broke down somewhere between Woop Woop and the back of Bourke, the arrival of a jovial, slang-talking, sun-weathered bushman on the scene was a true blue guarantee that she’d be right mate. Mick ‘Crocodile’ Dundee — Paul Hogan’s universally adored character — cemented this archetypal outback larrikin-cum-saviour into the collective subconscious of moviegoers.

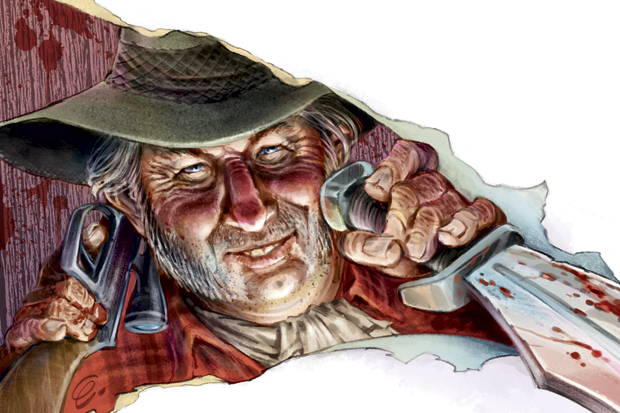

But post-2005, the last person any film-savvy tourist, stranded on some God-forsaken stretch of rural blacktop, would hope to encounter was a grinning ocker named Mick. Greg Mclean’s horror masterpiece Wolf Creek made sure of that. The film’s psychopathic antagonist, Mick Taylor — played with palpable menace by John Jarratt — was a public relations nightmare for bushies all.

Taylor is the dark reflection of Dundee: as quick with a joke, but even quicker with his ten-inch blade. The humour of Dundee’s oft-quoted ‘that’s not a knife’ spiel sours when Taylor appropriates the saying in Wolf Creek; just before slicing off a sobbing backpacker’s fingers and severing her spinal cord so she’s a paralysed ‘head on a stick’.

When Wolf Creek 2 opens in Australian cinemas on 20 February, it’s worth understanding the film’s significance, and not just in the aforementioned way the original movie turned pop culture’s trope of the helpful Aussie bushy on its Akubra-crowned head. The advent of the sequel indicates a sea change in the Australian film industry.

The great genre films of this country’s checkered cinematic history tended to be privately financed. Crocodile Dundee for one. Hoges and his partner John ‘Strop’ Cornell assembled much of that blockbuster’s $8.8 million budget from a slew of high-profile investors, ranging from Kerry Packer to Dennis Lillee.

Mad Max is another, albeit smaller budgeted, example. Director George Miller and producer Byron Kennedy stretched every penny of the $380,000 they piecemealed from backers to complete their dystopian epic, even resorting at times to paying extras and crew in beer. The now discarded 10BA tax deduction programme — particularly when its incentives were highest during the 1980s — facilitated the production of a rich assortment of privately funded and entertaining genre films.

Made by maverick Australian producers and directors like Tony Ginnane and Brian Trenchard-Smith, these ‘Ozploitation’ flicks were so disdained by Australia’s cultural elite that they were quite literally written out of our official cinema history books. Indeed Phillip Adams, champion of Australia’s government-financed film system (and one of the very first piggies at the tax-payer funded trough he help create) opined upon Mad Max’s release that the film should be banned due to its violent content.

The dream of Adams and his ilk, as he proclaims in the preface to the Australian Film Institute’s A Century of Australian Cinema, was to create a ‘boutique industry that made culturally specific films for upmarket audiences everywhere’. In other words, films made for and by inner-city sophisticates. It is a bias that long lingered.

Only a few years before the release of Wolf Creek, in an interview for Sarah Darmody’s book Film: It’s a Contact Sport, David Stratton, archbishop of this country’s film criticism, recommended that local film-makers leave American-styled genre film-making to Americans and focus on producing movies that can be marketed abroad as ‘arthouse releases’. But after decades of such snooze-fests failing at the box office, government funding bodies are slowly waking up to market realities. Even the original low-budget Wolf Creek acquired some government funding.

But Wolf Creek 2, upon losing its single significant private investor — whose original $5 million commitment would have amounted to almost half of the film’s budget — was bailed out by Screen Australia. A decade ago, this level of government investment in a horror film was unthinkable. Indeed Australia’s output of horror, thriller, sci-fi and action/adventure films is at an all time high. Almost 42 per cent of all Australian feature films made between July 2010 and June 2012, the most recent financial years analysed on the Screen Australia website, fall into these categories. In the previous two decades this figure had hovered around 20 to 25 per cent.

And get ready for a healthy selection of Australian genre films, many of which received government funding, that are hitting cinema screens this year. In addition to Wolf Creek 2 other promising titles include Drive Hard, The Babadook, Predestination, and John Doe: Vigilante.

It’s tough to rejoice over the government bankrolling any film, be it genre or arthouse. Movie-making is a commercial industry, which, if unsustainable on its own merits, shouldn’t be propped up as some elaborate work-for-the-dole scheme for Australian producers, casts and crews. But we should take comfort in the fact that this redirection in funding policy also represents a paradigm shift in the film bureaucracy’s mind set, a long overdue recognition that Australian audiences aren’t interested in kitchen-sink-drama yawn-fests dripping with PC ideology. And they sure as hell don’t want their tax dollars sunk into films that they won’t even buy tickets to see.

What they really want are exciting genre films. The kind long disdained by this country’s filmerati. The ‘American’ type. Best not to explain this to Mick Taylor though. He hates all things foreign. And you really don’t want to end up as a head on a stick.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Dean Bertram, a filmmaker and director in Sydney, is co-founder of A Night of Horror International Film Festival.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in