Florence was in fog the day I arrived. Its buildings were bathed in white cloud, its people moved as though through steam. The Arno river was a dense strip of dew. At the Piazzale Michelangelo, the statue of David was etched by the surrounding murkiness to a stark silhouette, the renaissance defined by gothic cloud. I peered through a telescope that overlooked the city and saw nothing for miles. My friend Alessandro told me this was unusual for sunny Tuscany, which made me feel quite pleased. Perhaps with each day that passed I would see less of Florence — the ultimate tourist experience. At a nearby cemetery, the milky arms of stone angels reached out through the brume, while creaking old Fiats disappeared into the ether. ‘I know it looks like England,’ Alessandro said, apologetically.

*****

The Tuesday before I had spent in a car trundling across the Italian countryside with a healer. I had been ill the past year, and my friend Mae, an American working in Siena, had located an ‘energy healer’ called Raffaello who said he could rebalance the energy centres of my body, or something to that effect. Because we were also short of time and had to travel from one Tuscan destination to another, Raffaello was willing to treat me in the car. He clambered in carrying several kilos of wholegrain flour — a gift for me, so I could make wholegrain bread, as bread from refined flour was unhealthy. It turned out the journey was a long one, but when he finally got out of the car, Raffaello would accept no payment. ‘You are the one healing yourself,’ he said.

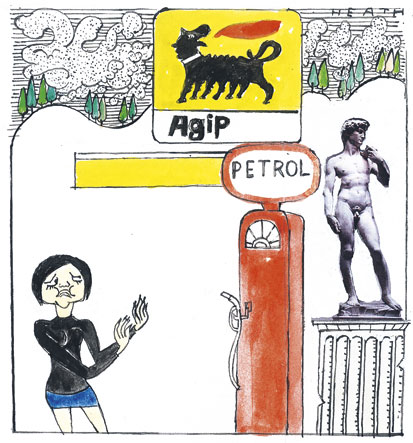

I also met a man in Perugia who dealt in homeopathic-type treatments, and who prescribed me many remedies. I could make out some of them, even though I don’t speak Italian — melatonina, magnesio, lipoic acid. Then — petrolio. In my mind, petrolio flourished as a pretty hillside herb. But Mae’s translation revealed it to be petroleum. A lot of people take petrol, the man said, via Mae. He mentioned the Rockefellers. I knew the Rockefellers drilled for oil, I didn’t know they drank it as well. I sniffed at the small bottle of petrolio he gave me — it was fuel all right. My instructions were to take several doses each day, five little drops each time.

Going back to Mae’s home, where I was staying, I placed the bottle on the dining table, whereupon its paraffin-like pungence spread to every corner of the room. I kept up the doses for several days, before I felt I had to stop. I was starting to smell like a BP station, evoking thoughts of diesel and kerosene, I am sure, everywhere I went. I steered clear of Mae’s stove whenever I was in her kitchen, in case my breath caught fire. The petrol did not make me feel better, or — reeking apart — any worse.

*****

As the fog lifted from Florence, the many hues of the city seeped back to life. With the red cap of the Duomo standing happily against a blue sky, I decided the town was better in Technicolor after all. One starry night, my friends and I stepped into a tiny restaurant where I had the meal of my life.

The chef was a sweaty, passionate man who lived to make the best Florentine dishes from the best Florentine produce. Under his firm guidance we ordered cold cuts, crostini and cheeses to share, and soon we had before us one large wooden board of prosciutto, salami, chicken liver paté, tripe, wild boar sausages and pecorino, along with some very good Chianti. I felt pure happiness. Chatting with us, the chef bemoaned how some tourists did not understand Italian dining, often ordering the secondi before the primi piatti, or having the wrong wine.

I suddenly realised why I was enjoying the meal so much. It was because the way we were eating reminded me of a slap-up Chinese meal, the kind where everyone digs into a common dish and there is none of this one-person-one-plate business. In my own parochial way, I was relating this Italian meal to my Cantonese childhood.

I thought of sharing this with the chef, then thought I’d better not.

*****

My last day in Tuscany, I stepped into the Galleria dell’Accademia to see the original David. There he was, proud and Goliath-sized, signalling the age of enlightenment, reason and a muscular faith in human ingenuity. What touched me most, however, was not David himself but the works of medieval religious art in the other galleries. These tempera paintings on wood, of Jesus, Mary and the saints, glowed in vivid colours against backdrops of gold. None of the artists were as famous as Michelangelo, in fact some were unknown.

For me, this anonymity shows a spirit of community rather than facelessness, a belief that one is only part of a bigger central story that binds us together. We have gained so much, now we live in the age of individuality. Might we have lost some things too?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Clarissa Tan is a staff writer at The Spectator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in