Rediscovering the unduly neglected is one of the chief excitements of those who curate exhibitions and write books. And there’s nothing I enjoy more than saluting the achievement of those who bring back to our attention an artist who – for one reason or another – has slipped off the art world radar. Before this exhibition and, more importantly, the book accompanying it, Alan Sorrell was only a name to me, with a few rather vague visual connotations. Now I can put definite images to the name and begin to build a context for his work. For anyone interested in the broader picture of 20th-century British art, the current Sorrell initiative is of real interest and value.

Although not precisely one of the famous generation of 1903 artists, Alan Sorrell (1904–74) was the contemporary of Edward Bawden, John Piper and Eric Ravilious, a Royal College of Art student who made a name for himself as a painter of imaginative narratives. His professional career was not lucky: he was turned down as an official war artist (he remained on the reserve list but did manage to sell some 26 pictures to the War Artists’ Advisory Committee between 1941 and 1946); later he was sacked from his teaching post at the Royal College by the new principal, Robin Darwin; and although he was a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy, he was never elected a member.

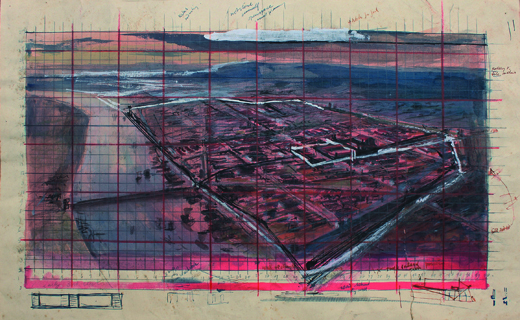

Despite these setbacks, he worked consistently and was particularly successful as a ‘reconstruction artist’, making drawings of historic sites and monuments as they were in their heyday. These scenes of everyday life in ancient times were immensely skilful explorations of the archaeological imagination, and must be accounted Sorrell’s most remarkable (and oddly original) work.

The book is subtitled ‘The Life and Works of an English Neo-Romantic Artist’, and is edited by Sacha Llewellyn and Richard Sorrell (Sansom & Co., £25). It contains essays by a variety of specialists in the field, such as Peyton Skipwith and Alan Powers, and succeeds in providing a good all-round account of Sorrell’s artistic career, from his years at the British School at Rome (1928–30) to his mature achievements as a muralist and reconstruction artist. However, I’m not sure I would want to identify him so wholeheartedly as a Neo-Romantic — useful, in terms of categorising him and selling his work, as such a term undoubtedly is. Although he shared certain characteristics with the Neo-Romantics, he was also indebted to classicism and surrealism, and was historically accurate in a way that runs counter to the intuitive interpretations of the Neo-Romantic instinct. The book’s range of illustrations offers a far more convincing introduction to an unknown artist than the somewhat meagre display at the Soane Museum.

The exhibition consists of just two small upstairs rooms, which most visitors were passing through at some speed, perhaps in search of more dramatic visual fare. There are few framed pieces as most of the drawings and paintings are simply mounted and displayed in wall cabinets. This distances them somewhat from the viewer, and, combined with low lighting levels, makes looking difficult. There are some good drawings (especially a 1928 self-portrait) and strong wartime studies, but the show doesn’t really do Sorrell justice; buy the book instead.

At the beginning of January, the publisher, author, art critic and collector T.G. Rosenthal died at the age of 78 after a long fight with cancer. I got to know him through a shared enthusiasm for the sophisticated paintings of L.S. Lowry, who is often thought — quite wrongly — to be a naive artist. When I published a small book on Lowry, Tom sought me out, and we became friends. We found we had other interests in common: the art and writing of two 20th-century mavericks, Wyndham Lewis and Michael Ayrton (whom Tom thought of as the older brother he’d never had), as well as Modern British painting and sculpture in general. And remembering back to my student days, my original curiosity about Ayrton and Lewis had been encouraged by Tom’s own writings. He was a determined critic and broadcaster and wrote extensively about his passions: Ivon Hitchens, Sidney Nolan, opera, Paula Rego, Jack Yeats.

Tom was an occasional contributor to The Spectator, as exhibition or book reviewer, and an eagle-eyed reader of the magazine, always full of comments about the latest issue. After a lifetime publishing other people’s books (he started at Thames & Hudson and was promoted to managing director there before moving on to run first Secker & Warburg and then André Deutsch), he returned to criticism and art history and continued writing prolifically until at last illness robbed him of the energy. He was particularly proud of his Lowry monograph, published by Unicorn Press in 2010, the fruit of a lifetime’s thought about the artist. His passion for Lowry’s work led him in 1960 to thrust all the money he had into the artist’s hands in return for a small oil painting. Tom’s advocacy of Lowry was crucial in helping to break down establishment disdain for this popular northern industrial painter, a change of heart that resulted in the long-awaited exhibition of his work at the Tate last year. Tom’s Lowry book was reissued in paperback and sold well alongside the rather dry and dusty catalogue: the Rosenthal book is far more widely informative and readable.

When I think about Tom, I remember the gusto with which he enjoyed things: art, music, books, theatre and film, food and wine, people. He had a great appetite for life, decided opinions about all aspects of it, a boundless collection of stories about friends and foes, and a warmth of appreciation that was truly life-enhancing. Exactly a month before he died, I attended the inauguration of the Tom Rosenthal Art Library at his old Cambridge College, Pembroke. Although by then seriously ill, Tom launched himself into a speech replete with polished anecdote and extemporised comment, and ended by saying that his father had always counselled ‘giving with a warm hand’. Although he had intended to leave his art library to Pembroke in his will, why not give it while he was still there to enjoy the process? It was clear that he took great pleasure in this last public act, and it was a privilege to be there to witness it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in