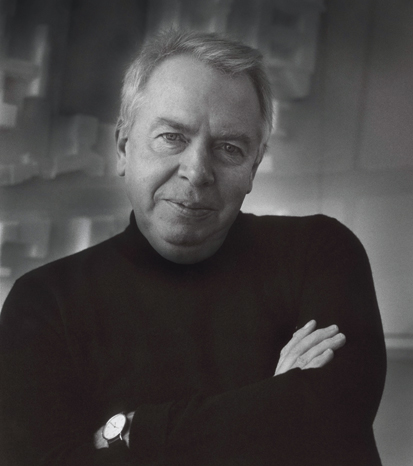

For a man who’s about to celebrate his 60th birthday, Sir David Chipperfield looks remarkably fresh-faced. His pale blue eyes are bright and piercing, his thick white hair is cut in a fashionable short crop. Clad in a dark polo neck, he looks almost boyish. This youthful vitality is reflected in his work. At an age when most of us tend to start slowing down, he’s busier than ever. His offices in London, Berlin, Milan and Shanghai employ more than 200 people. His current projects range from Paris to St Louis.

I meet him in his groovy high-rise office overlooking Waterloo Station. He’s just flown in from Mexico City, where he’s built yet another new museum. Married with four children, he lives in a large apartment near Regent’s Park, but he’s also built himself houses in Berlin and Galicia. A lot of his best work has been abroad. Though he’s held in high esteem in Britain (a knighthood, a RIBA Gold Medal…), he’s far more famous in Germany, where his audacious rebuild of Berlin’s Neues Museum was front-page news.

An awful lot of architects seem determined to shock and startle. Chipperfield’s buildings are striking, but they don’t clamour for attention. His subtle museum extensions in Zurich and Essen are a seamless blend of old and new. Whether it’s a high-rise hotel in Hamburg or a shopping centre in Innsbruck, he’s shown that modern architecture can co-exist with its surroundings, so long as it makes some concessions to local style and scale. ‘How can you build something in a place that seems to belong to that place?’ he says of his understated style.

Chipperfield was raised on his father’s farm in Devon and educated at Wellington School in Somerset. ‘I spent half my time on the sports field,’ he says, ‘and the other half in the arts room.’ He was blessed with an inspiring art teacher, who ignited his interest in architecture, but sport was just as formative. ‘I wasn’t a particularly talented athlete but I was completely determined,’ he reveals. ‘Application and commitment can take you a long way. That was an enormous lesson to me. I wanted to win more than other people wanted to win, and I was willing to put the time in.’

He trained at Kingston School of Art and the Architectural Association, and started his career in the late 1970s. The economy was in the doldrums, and modern architecture seemed to have run out of steam. ‘Architecture was really in a very difficult place,’ he says. ‘Modernism was on the floor, and being kicked — in a way, rightly.’ Battered and bewildered by brutalism, the public had lost confidence in modernist design. ‘Architecture, in all its guises, was demoralised,’ he recalls. ‘Architecture was disliked by society. Modern architecture was frowned upon.’ This distaste was understandable. ‘Our city centres did look bad.’

Chipperfield worked for Richard Rogers, and then for Norman Foster. ‘Architecture suddenly looked sexy again.’ Energised by their example, he set up on his own. His first big break was a new shop on Sloane Street, built for the Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake. Commissions in Japan soon followed. ‘I was there once a month for five years. I had an office there. My first three buildings were in Japan.’ Japan confirmed his faith in modernism. ‘There’s great care and sensitivity about doing simple things.’

His subsequent work has been distinguished by its oriental simplicity and serenity, but his fellow Britons haven’t always been so serene. When he built a new house for his friend, the photographer Nick Knight, some of Knight’s suburban neighbours campaigned against it. ‘They wrote to Prince Charles. It wasn’t about a house. It was about the fact that their cosy vision was being challenged.’ It was a harsh but useful lesson. Chipperfield realised there was a lack of trust. He learned to meet his critics halfway. ‘The modern movement was very arrogant about what people expected architecture to be. They had a big picture: “The world is changing, we’re going with it and if you can’t see it, forget it. We’re not interested.” We can’t take that view any more. I think we have to accept that we are trapped by history. We are conditioned by history, and that’s part of the richness of culture.’ When he curated the architecture biennale in Venice, he called it Common Ground. ‘I feel that architecture depends on us understanding better those things that we share.’

His River & Rowing Museum in Henley was a good example of this pragmatism. The locals wanted something traditional, Chipperfield wanted something modern, and his search for a shared aesthetic resulted in an even better building. ‘It was regarded as a good piece of modern architecture and yet Henley liked it.’ He softened his design with weathered wood, creating a bold contemporary building that still felt at home in this riverside location. ‘It was a Trojan horse in a way,’ he says, ‘but it was very well received.’

Sadly (for us Brits, at least) most of Chipperfield’s landmark buildings have been built overseas — particularly in Germany, where attitudes to modernism are more progressive. However, every nation has its bogeymen. In Germany neoclassicism is the big bête noire, on account of its associations with the Nazis. Chipperfield confronted this taboo in his Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach. Its tranquil colonnades freed neoclassicism from its fascist connotations, and won him the Stirling Prize.

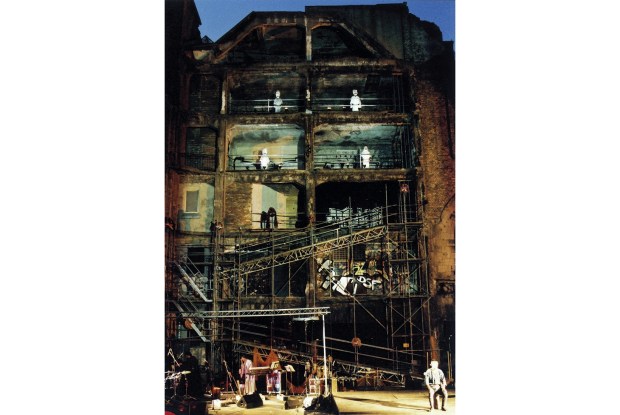

Chipperfield’s greatest German project was his reconstruction of Berlin’s Neues Museum (and, subsequently, the master-plan for the Museum Island that surrounds it), a grand projet that has engrossed him for more than a decade. He could have simply restored the original structure, which had stood empty since it was reduced to ruins at the end of the second world war. Instead he chose to supplement these ‘historical fragments’ with something new. ‘We tried to make a modern building out of the old building, but with huge respect for what was there. We maintained every historical element, without removing anything, but incorporating that into a new building, which was a mediation between the original building and a new museum.’

Inevitably, this approach was bound to ruffle a few feathers. ‘I was playing not only with architectural expectations but, in a way, cultural expectations — and not only with local residents, but probably the whole nation,’ he says. ‘That debate was quite hostile.’ There were candlelit protests outside the building site, but Chipperfield stood his ground. ‘We want people to be interested in architecture,’ he told his German friends, ‘so we can’t complain when they are.’ Eventually he won the argument. Even the tabloid press came round. ‘What I enjoy in Germany is that there is fierce discussion, but it’s very well articulated.’

And Germany has returned the compliment. ‘When Cameron came to see Angela Merkel, I went to a dinner for 12 people and met my own Prime Minister. I was introduced by Angela Merkel as “one of our most famous German architects”!’ Now he’s renovating two of Germany’s most iconic galleries: Munich’s intimidating Haus der Kunst, site of Hitler’s ‘degenerate’ art exhibition, and Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, designed by Mies van der Rohe, whose historic dictum ‘less is more’ could have been coined with him in mind.

For Chipperfield, what a building feels like is just as important as what it looks like. ‘To be fond of architecture is certainly better than to be surprised or amazed.’ And finally, Britain is waking up to his humane modernism. His Turner Contemporary revitalised the Margate seafront. His Hepworth gallery in Wakefield was the biggest new art museum to be built in Britain for 50 years. Other recent projects include houses in Kensington and the Chilterns, and an office block in King’s Cross. ‘I like that building a lot.’ Ironically, the office block where we’re talking today is earmarked for potential demolition — part of his plan to redevelop Waterloo. During the past 30 years, much of Chipperfield’s time and talent has been spent enhancing foreign cities. Here’s hoping the next 30 years bring him many more commissions closer to home.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in