For 17 years I have been reporting on one of the most haunting tragedies of our modern world — the ruthless persecution of the last survivors of the original inhabitants of southern Africa, the bushmen, by a policy seemingly designed to wipe them from the earth. Those responsible are not wicked white colonialists but the government of Botswana, which, thanks to its vast diamond reserves, is per capita the richest country in Africa. We in Britain, however, should take a special interest in this story because through most of that time our Foreign Office has given full support to the policy which created this tragedy, in breach of a solemn pledge we gave to the bushmen in the 1960s. And now there has been yet another disgraceful twist to the story.

The outside world was first made dramatically aware of the little bands of bushmen living in the Kalahari nearly 60 years ago, through a series of documentaries made for the BBC by Laurens van der Post. Those films, and his book The Lost World of the Kalahari, gave an unforgettable picture of a way of life which could not have seemed more remote from the modern world. Although these bushman hunter-gatherers were still in effect living in the Stone Age, van der Post showed how their stories, dances and spiritual beliefs gave them a sense of living at one with the natural world and the universe. His book became a major bestseller because it conveyed a spiritual message which struck a deep chord with countless readers.

Bushman of the Kalahari Photo: Getty

Bushman of the Kalahari Photo: Getty

In 1961, thanks not least to van der Post, the British rulers of Bechuanaland, as it was known, designated an area twice the size of Wales as the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, designed to protect the last refuge of a people who had lived across southern Africa for tens of thousands of years until they were gradually exterminated by all the races who came after them. This guarantee that they could live in the reserve unmolested was enshrined in the new country’s constitution when Botswana won independence in 1966.

But in the 1980s diamonds were discovered in the CKGR. In 1996 a Botswanan minister entered the reserve to tell the bushmen, despised in the capital Gaborone as sub-human ‘remote area dwellers’, that they must move out. What the government hadn’t reckoned on was that the bushmen had found a remarkable spokesman. John Hardbattle’s father had come to South Africa in the Boer War and in his old age had fathered three children by a bushman wife. On his father’s death, John and his two sisters were sent to live with an aunt in England, where they were educated and fully westernised.

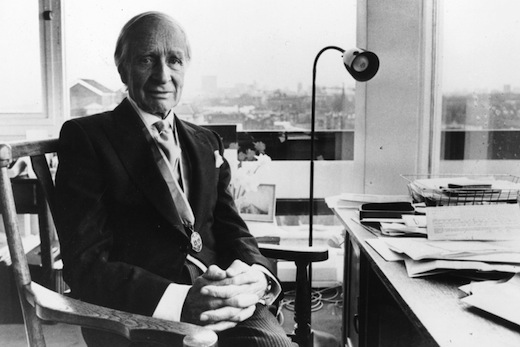

Sir Laurens Van de Post, 1987 Photo: Getty

Sir Laurens Van de Post, 1987 Photo: Getty

But John then returned to farm next to the CKGR and became a champion for his mother’s people, uniquely equipped to alert the outside world to the crisis confronting them. In Washington, he addressed sympathetic senators and congressmen. At Sir Laurens van der Post’s invitation he came to London, accompanied by a bushman from the reserve, Roy Sesana, and I met them there just before Laurens flew with them up to Balmoral to brief his friend Prince Charles.

Tragically, by the end of that year, 1996, not only was Laurens dead, aged 90, but also John Hardbattle himself, from cancer. Although the first of several thousand bushmen had been evicted from the reserve, the world had by now been aroused to enough concern for the Botswanan government to stay its hand on more evictions. But by 2002 it had set up a grim settlement on the edge of the reserve, New Xade, into which ever more bushmen were being forcibly moved. Uprooted from all the world they knew, they fell to pieces, drunkenly losing the will to live in what they soon called ‘the place of death’.

By now, however, the bushmen had found another key ally, the charity Survival International, which campaigns for indigenous peoples across the world. The battle lines were being drawn up. On one side was Survival and the bushmen, with Roy Sesana as their chief spokesman; on the other was the Botswanan government, claiming that its only purpose was to give the primitive bushmen access to the benefits of civilisation, such as medical care and education. In this hypocrisy it was supported by our own Foreign Office and the EU, both parroting the Gaborone line. A superb BBC documentary at this time showed a toe-curling visit to the Kalahari by Glenys Kinnock MEP. At a carefully staged ‘meeting’ with the bushmen, Sesana was prevented from speaking.

Roy Sesana speaks about the Botswana government’s eviction of his people from their ancestral lands Photo: Getty

Roy Sesana speaks about the Botswana government’s eviction of his people from their ancestral lands Photo: Getty

Survival now recruited an able British human rights lawyer, Gordon Bennett, to launch what was to be the longest case ever to go through the Botswanan courts, which in December 2006 culminated in an extraordinary victory. The Supreme Court ruled that the bushmen’s constitutional right to live unmolested in the CKGR must be upheld. Many hundreds returned to the reserve. In particular the judges also castigated the government for its cruel efforts to shut off the bushmen’s vital water supply.

Despite this, armed guards continued to deny the bushmen access to water. In 2011 Bennett won a court ruling that the main water borehole must be kept open. Still Gaborone’s reign of terror persisted, now focused on the bushmen’s hunting of game. This resulted in a series of vicious episodes where they were arrested, tortured or shot.

Kalahari Bushmen carry a water tank Photo: Getty

Kalahari Bushmen carry a water tank Photo: Getty

This year, thanks to Survival, the bushmen were preparing yet another court case. There were only two problems. One was that the government had now repealed that article of the constitution guaranteeing them their rights. The other was that it barred Gordon Bennett from entering the country.

Now comes the shocking news that, in his enforced absence, the High Court has imposed devastating new restrictions on the bushmen. The only people allowed to live in the reserve will be the 189 named as bringing that victorious case in 2006, and their relatives will be given only short-stay permits to visit them. Further, they will be allowed no more permits to hunt game for food.

In 2010 an ‘eco-tourist’ company was allowed to open a ‘safari lodge’ in the CKGR, complete with a swimming pool full of the water the bushmen desperately needed, with armed guards to keep them away. Now the bushmen are forbidden to hunt for food. In desperation, Survival is calling for tourists to boycott Botswana. But for the moment it looks like game, set and match to Botswana’s President Ian Khama, winner of international awards for his ‘conservation’ work, for whom driving the bushmen from their home has become a personal crusade. Meanwhile, diamond mining, long denied by Gaborone as its reason for expelling the bushmen from their last refuge on earth, proceeds apace. This is a victory for modern civilisation of which no one can be proud.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Christopher Booker is a columnist for the Sunday Telegraph.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in