Why would anyone want to adapt Berg’s Lulu, a masterpiece even if a problematic one? According to John Fulljames, who is the producer of the version of Lulu that Olga Neuwirth has come up with, ‘the Lulu plays now stand neutered within the familiar history of male authored texts which define women from a male perspective…Neuwirth turns this on its head. For the first time, Lulu is allowed to tell her own story…We [the audience] listen and watch but do nothing and so become complicit in her nightly repeated murder.’ How can people talk such nonsense? If Fulljames wants us to leap on to the stage and prevent Lulu’s murder, he is just joining the legendary spectator who did leap on to the stage to prevent Othello stifling Desdemona, a textbook case of someone confusing an actor with the character he portrays.

And as for telling the story from Lulu’s perspective, I’d have thought that one of the striking things about both Wedekind’s Lulu plays and Berg’s opera is that they seem not to be told from a perspective at all, the Ringmaster who opens the opera quickly disappearing and being an odd irrelevance. Of course the playwright and the composer couldn’t help being male, but I don’t see that Berg’s opera shows Lulu as depraved or victimised or whatever from a male standpoint, any more than Neuwirth’s ‘adaptation’ shows her as any of those things. And it is disingenuous of Neuwirth to write: ‘The composers of the Second Viennese School are well known for making adaptations of works by other composers’; they made arrangements of orchestral works for chamber groups, so that they could get performed more easily, but they didn’t mess around with them.

American Lulu is set between the 1950s and the 1970s, allowing Neuwirth not only to beat the drum for women’s liberation, but also for civil rights, so we get excerpts from Martin Luther King slotted in quite arbitrarily. Civil rights would be, maybe has been, a good operatic subject, but Lulu is already quite enough of a handful as she gets through lover after lover, usually disposing of them with a pistol. American Lulu is much shorter than Berg’s opera, which Neuwirth has selected passages from and reorchestrated, as well as writing her own Act III, which Berg left only in sketch form.

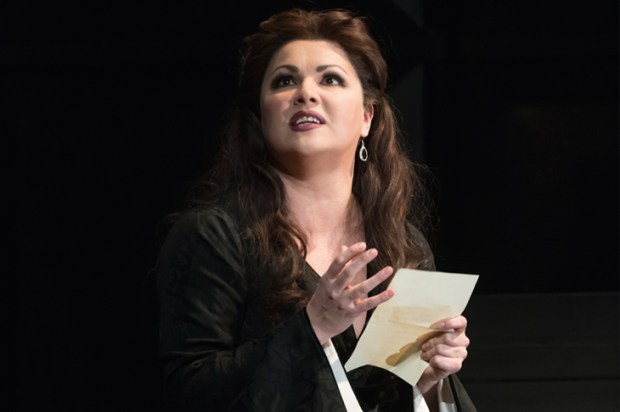

This production, a joint effort of The Opera Group, Young Vic, Scottish Opera (it was performed at the Edinburgh Festival) and Bregenz Festival, does it ample justice, though I wish the American accents weren’t quite so spasmodic. Lulu is taken by Angel Blue, a sensationally sexy artist with a strong, lovely voice; it would be great to see her in Berg’s opera. Her male victims are impressive, too, especially Donald Maxwell, still on great vocal form. Jacqui Dankworth as Lulu’s lesbian would-be lover is less successful. She is required to sing blues, which indeed Dankworth often does, but Neuwirth’s music for her is so banal that the character — quite the most sympathetic in the opera (from a male perspective) — remains a cipher. The London Sinfonietta under Gerry Cornelius plays with its usual aplomb.

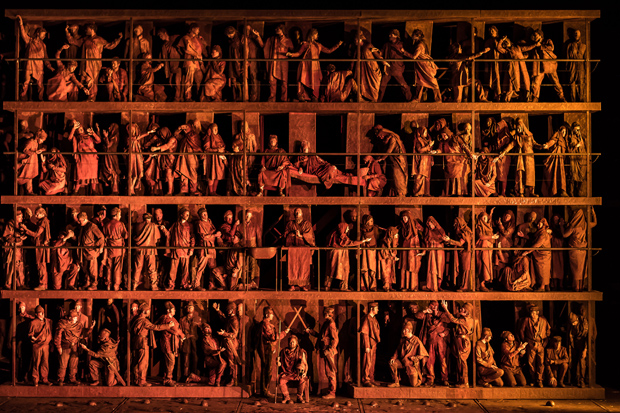

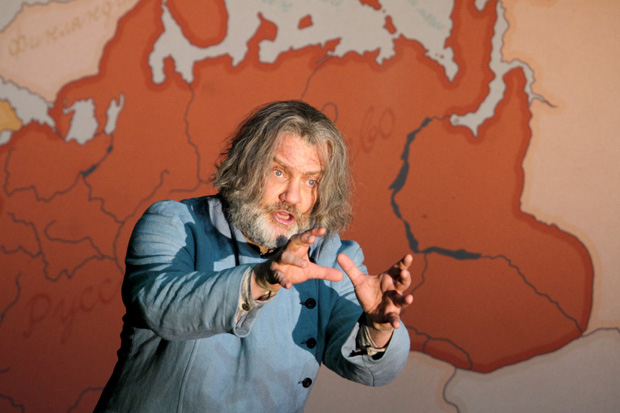

The Royal Opera’s second offering of the new season is Le Nozze di Figaro in David McVicar’s production, for which he has returned and added quite a few touches. There is slapstick, such as the oldsters Marcellina and Bartolo rolling around on Susanna and Figaro’s bed. But the predominant tone is darker than usual, perhaps in line with John Eliot Gardiner’s conducting. He takes the overture at an extraordinarily rapid pace, and in general the arias and ensembles are fairly brisk, while the recitatives are delivered more or less as they would be if they were in a spoken play. That actually makes the drama more compelling. But I was unable to forget Colin Davis’s adoring and penetrating handling of this score three years ago, where one wept both because the work is so beautiful and because it is so moving.

This revival has a strong but not the strongest cast. The towering figure of Luca Pisaroni as Figaro means that he has an advantage over the Count of Christopher Maltman, but the extreme tension between the two men was missing. Maltman’s Count relies entirely on rank and threatened force rather than charm, which takes away a crucial element from the drama. Lucy Crowe, however, is so beguiling a Susanna that it’s hard to mind about anyone else if she is happy. Maria Bengtsson took risks by playing the Countess as such a pained creature that she sang more quietly than anyone else, making one wonder whether that is her interpretation of the part or whether she was having an off-night, though since her voice seemed perfectly controlled I decided on the former. Renata Pokupic sang a breathless Cherubino. I wonder why the chorus in Act I was so restrained — surely the Count would have been offended by such muted praise? Still, perfect performances of this perfect work are rare, and this one was certainly enjoyable enough to be worth going to.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in