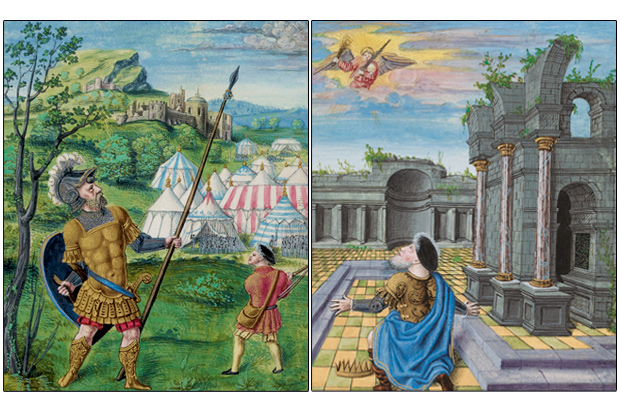

As parvenus, the Tudors were unsurpassed. In the early 15th century no one would have predicted that within a couple of generations these minor Welsh land-owners would mount the English throne and rule the kingdom for more than 100 years. Notwithstanding their ‘vile and barbarous’ origins, their name would become synonymous with historical glamour and the ruthless exercise of regal power.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Anne Somerset’s books include Elizabeth I and Ladies in Waiting: From Tudors to the Present Day.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in