The frantic promotion of the proposed HS2 rail line — a white elephant in the making — is a reminder to those of us living outside London that we suffer from a disability: one so severe that it is worth spending £40 billion to shorten the journey to the capital by a few minutes. Our condition will get worse as centralisation proceeds and London’s gravitational force becomes ever stronger. Eventually ‘the provinces’ will evacuate their contents into the south-east, and England will be a megalopolis surrounded by deserted villages, towns and cities. Such are the apocalyptic thoughts of someone who now finds himself having to travel from Stockport to London several times a week because that’s where the events, meetings, headquarters or whatever are to be found. This week, I had to spend four days in London to participate in the national conversation.

London is sometimes a compromise meeting place for provincials holed up in different corners. So this was where, on Tuesday, I met up with Raja Panjwani, who is studying the philosophy of physics at Oxford. He has agreed to subject the MS of my next book — Of Time and Lamentation. Reflections on Transience — to critical examination. The book aims, among other things, to snatch time from the jaws of physics. For many people (and not just physicists) the last word on time — its nature, its existence or nonexistence, its relationship to everything else in the universe — is whatever physics says it is. If Einstein says that the difference between the past and future is an illusion, then it is an illusion. If physicists, in the course of developing a Theory of Everything, find they can do without time, then time is unreal. This dismissal or reduction of a mysterious and fundamental facet of our existence is an egregious form of scientism.

Back to London on Thursday to chair the Steering Committee of Healthcare Professionals for Assisted Dying (HPAD). This group was co-founded by an immensely brave and visionary general practitioner, Ann McPherson, when she was seriously ill with pancreatic cancer. She was outraged that the so-called representative bodies of the medical profession such as the BMA and the Royal College of Physicians overrode both public opinion (80 per cent in favour, 75 per cent of those with religious beliefs) and the views of 30-40 per cent of their members, by opposing legalisation of physician-assisted dying for terminally ill people with unendurable symptoms. Anyone who believes that good palliative care renders such a law unnecessary should read the account of Ann’s death (written by her daughter Tess, herself a hospital consultant). It makes harrowing reading.

And so to Friday, the 65th birthday of the NHS, the fifth day of an NHS-packed week: Monday, the launch of my book NHS SOS; Tuesday, a defence of a non-privatised NHS against the combined forces of Stephen Dorrell and Alan Milburn at the Royal Society of Arts; and Wednesday, an appearance on the Daily Politics to disagree with Tory doctor and MP Daniel Poulter. But today I am on home territory. Our little group, Stockport NHS Watch, chaired by my wife Terry, was formed to document the consequences of Andrew Lansley’s Health and Social Care Act (2012) which, as I have pointed out before, has the therapeutic value of a Semtex suppository. We joined one of many celebrations in Trafford, where the first NHS patient was treated. Our huge polystyrene birthday cake, with an axe marked ‘Privatisation’ embedded in it, reflected our fear that this birthday might be the last. That Lansley’s plans for marketising the NHS got through parliament without electoral mandate is a terrible reminder of the democratic deficit in Britain today. The extent to which the Bill was influenced, promoted and eased in its passage through parliament by individuals who stand to benefit personally would make Transparency International blush.

And so to the weekend, sitting in the sun, writing the Guardian obituary for one of the most admirable people I have ever known. John Brocklehurst, emeritus professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Manchester, died peacefully just before his 90th birthday. His commitment to making the world a better place was unchanged from the time when, as a devout Christian, he joined the Grenfell Mission in Labrador, to his later years when he became an avowed humanist. There could be no better demonstration that morality does not necessarily require religious underpinning. In our many conversations in recent years, we never discussed Cameron’s Big Society — where the rich shall get richer and the weak shall go to the wall. It would have disgusted and depressed us too much.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

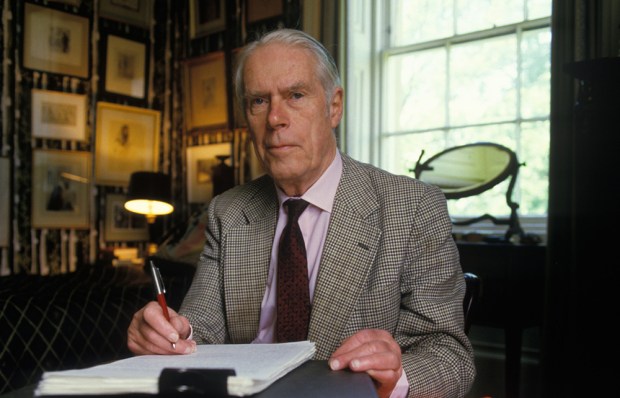

Raymond Tallis is a philosopher, a cultural critic and a former clinical scientist

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in