The two main harms of government regulation, to be balanced against any benefits, are cost and delay. But there is another harm, rarer but lethal when it happens. Sometimes regulation perversely increases risk by lulling the regulated business or people into a false sense of safety.

I had this thought last weekend as I watched a football match on television. My beloved Newcastle United beat Aston Villa in the FA Cup fourth round, but the match made headlines because of five bafflingly bad decisions taken by the referee and his linesmen: failing to award two clear penalties, failing to give a red card for a dangerous tackle and failing to spot two offsides that led to goals.

Four of the five decisions went against my team but that is not my point. Because it was the FA Cup, there was no Video Assistant Referee (VAR) to check and overrule the ref. Whereas some say this proved the need for VAR, Alan Shearer made a more perceptive comment: ‘If you ever needed any evidence of the damage VAR has done to the referees, I think today is a great example of that. These guys I think look petrified to make a decision today because they didn’t have a comfort blanket. For me, they’re actually getting worse.’ In other words, the introduction of new technology to help referees has made them less good at their job.

The same thing happened in the run-up to the financial crisis. There was plenty of regulation of banks, indeed the volume and detail of regulation increased significantly before the crash. The Financial Services Authority (FSA) crawled all over banks, demanding to see how they handled various risks. The widespread notion that deregulation caused the crash is nonsense. It was the under–regulated hedge funds that came through the crisis in best shape precisely because they had no comfort blanket.

As the 15 authors of one 2009 study, led by Philip Booth of the Institute of Economic Affairs, concluded: ‘Though [we find] that statutory regulation failed, and that market participants took more risks than they should have done, it appears that statutory regulation made matters worse rather than better.’ This is partly because regulators were obsessed with one kind of risk and neglected another. Credit risk (whether borrowers could pay back money they had borrowed) was the constant concern of the regulator. Liquidity risk (whether lenders might stop supplying funds) was often barely mentioned. Yet it was mainly liquidity drying up that brought down the mortgage banks and many other institutions.

The widespread notion that deregulation caused the financial crash is nonsense

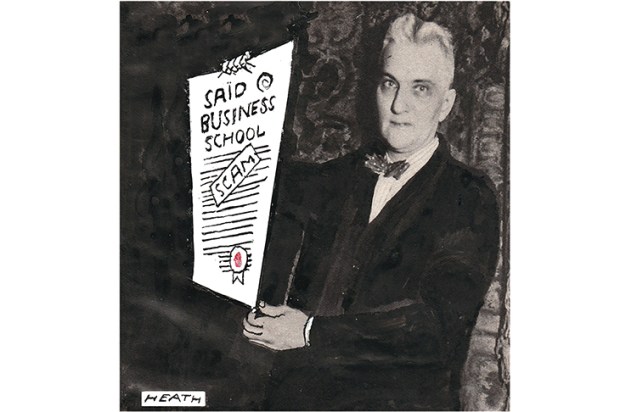

Credit risk in Britain turned out to be roughly as the banks had calculated; liquidity risk turned out to be much higher. Why had the boards of banks not taken more notice of the risks they were running on the borrowing side? Because the regulator inadvertently reassured them by neglecting the topic. Said the bulls to the bears on the boards: ‘The FSA’s not worried, so why are you?’

Moreover, as John Kay and Mervyn King pointed out in their book Radical Uncertainty, the regulated banks had got into the habit of putting a number on every risk, to indicate probability multiplied by impact. They did this to satisfy the regulator. In effect, this turned regulation into a box-ticking operation. But some risks were unquantifiable, so putting numbers on them misled the risk committees of these banks and the regulators too. ‘The biggest mistake governments made was to pretend they knew more than they did,’ said Kay and King.

In America, regulators made a worse and rather less subtle mistake in the early 2000s. The American government decided that sub-prime lending should be encouraged in order to help more poor people and minorities to get mortgages. They did this mainly by ordering two huge, government-backed entities, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, to drive up the proportion of sub-prime mortgages.

With a government guarantee behind their borrowing, the two went out and bought portfolios of mortgages off lenders, who happily responded by abandoning almost all restraint on sub-prime lending. Why do we care whether this chap can repay his loan, they asked themselves, if others are going to take the loan off our books? Why do we care, said Fannie and Freddie, if the taxpayer is guaranteeing us? By 2008, when the music stopped, Freddie and Fannie held more than $2 trillion of such loans with high default rates and high loan-to-value ratios. They had spent $175 million lobbying to defend their government guarantee.

The late John Adams of University College London wrote a book about a general human tendency for ‘risk compensation’: if you make our lives safer, we will take more risks. People wearing seat belts drive faster, other things being equal, than those not wearing them. American states that brought in laws mandating the use of motorcycle helmets saw relatively more motorcycle accidents than those that did not. A spot where a rural road crossed a railway in Canada, with no gates or warning lights, was rendered ‘safer’ by cutting down trees so cars could see if trains were coming – the result was an accident for the first time, because cars slowed down less.

Conversely, Sweden’s ‘Hogertrafikomlaggningen’ in 1967 – when, overnight, drivers switched to driving on the right – caused a temporary reduction in accidents, as drivers compensated for the expected increased risk by driving more carefully.

Of course, this argument shouldn’t be taken too far. Regulation does help reduce risk: speed limits, drink-driving laws, bans on texting while driving all help. Yet if you try to explain to a regulatory body that badly designed regulations might sometimes make things less safe, they just don’t get it. For regulators, human beings are automatons that obey or disobey rules, not thinking creatures that respond in subtler ways to incentives. Give referees the comfort of knowing a video replay will confirm or overrule their decisions and you don’t make their decisions better, you make them worse.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.