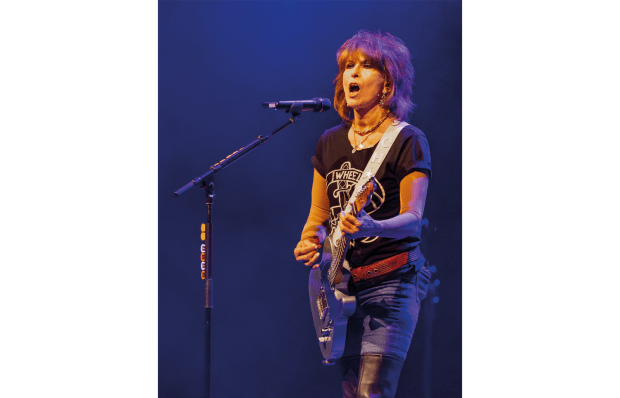

Somebody obviously thought it a good idea that Emmylou Harris play her last ever Scottish show in a soulless sports hall in the east end of Glasgow. Built for the 2014 Commonwealth Games, the feel of the Emirates Arena on a chilly January night was less Sweet Home Alabama, more Home Counties Ikea.

As well as kicking off this year’s Celtic Connections, the city’s annual festival of roots music, Harris was also kickstarting her farewell tour of Europe. She plays her final UK shows in May, including one at the Royal Albert Hall, which seems a more fitting setting for a regal adieu than a pimped-up cycling track. Presumably, the choice of venue was a numbers game. Whatever the reason, it was a poor one.

There will be good reasons why Harris is stepping off the road, but waning powers isn’t one of them

Not that Harris seemed to mind. One got the sense that you could drop her into a war zone and she and her band, the Red Dirt Boys, would still muster up a performance filled with grace and poise.

She maintained a vibrant, energetic presence throughout a set that acknowledged her unique, somewhat ambivalent position in the country music pantheon. She might be more or less the same age as Dolly Parton, but musically Harris belongs to a generation one further step up the line. Hailing from Alabama, she started out in the folk clubs of Greenwich Village and later formed a partnership with Gram Parsons, the doomed princeling of Americana music in whose footsteps every wannabe cowboy-booted troubadour has since attempted to follow.

She has recorded with Bob Dylan and Neil Young, and her music unaffectedly embraces folk, bluegrass, blues and rock, as well as the plain art of the singer-songwriter. Her trio of classic albums from the second half of the 1970s – Pieces Of The Sky, Elite Hotel and Luxury Liner – may have forged her reputation, but her records of midlife rejuvenation and reinvention – Wrecking Ball, Red Dirt Girl and Stumble Into Grace – are equally impressive.

Whatever the era or genre, for Harris the voice and the song have always been the thing. Regarding the former, at 78 that bright, silvery blade has inevitably lost a little of its sharpness, but a few rougher edges were not unwelcome. She moved easily from cowpoke rowdiness – a race through ‘Two More Bottles Of Wine’ and a closing swing at Chuck Berry’s ‘You Never Can Tell’, tossed in ‘just for fun’ – to spiritual communion on ‘Help Him, Jesus’. The a capella harmonies on ‘Bright Morning Stars’ were magnificent.

As for the songs, there was a sense of her chatting to old friends as she visited material written by Parsons, Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, Gillian Welch, Nanci Griffith and Mark Knopfler. Of her own compositions, the distressed reverbed blues of ‘Red Dirt Girl’ and a heartbreaking ‘Boulder To Birmingham’ shone. There will be good reasons, I’m sure, why Harris is stepping off the road, but it was clear that waning powers isn’t one of them.

Goodbyes were in the air at Celtic Connections. A few days after appearing at a concert honouring Dick Gaughan, the great Scottish singer, guitarist and radical, Martin Carthy announced, via his daughter Eliza, that he was suffering from late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Carthy was pulling out of a forthcoming tour, she said, drawing the curtain on one of the most significant careers in British traditional music stretching back more than six decades.

Carthy is 84 and has looked frail of late, not least when he played at the awards show for the Mercury Music prize, for which his most recent album, Transform Me Then Into A Fish, was nominated.

Let the record state that the last of his many thousands of public performances was a touching if understandably tentative rendition of the traditional ‘Bonny Woodhall’. It was a poignant moment during a stellar show, which included contributions from Billy Bragg, Deacon Blue’s Ricky Ross and Lorraine McIntosh, Kris Drever, Martin Simpson and a host of others, all of whom had gathered to celebrate the profound influence of Gaughan on the art of the song as a tool for human empathy, social resistance and historical accounting.

Karine Polwart’s ‘Craigie Hill’ and Lisa O’Neill’s ‘The Wind Doesn’t Blow This Far Right’ were among the many highlights. Gaughan himself was forced to retire in 2016 following a stroke, though it was heartening to see him on stage at the end, singing ‘The Shipyard’s Apprentice’ and among the ensemble on Hamish Henderson’s ‘Freedom Come-All-Ye’.

It was moving, uplifting and melancholic in equal measure. Gaughan, like Carthy and Harris, stands as a titan upon his own particular patch of earth. When they fall silent, voices of this order can’t ever be replaced.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.