It’s been almost a full decade since Britain voted to leave the European Union. Inside Labour, whatever words are muttered about accepting the referendum’s result, the consensus remains that Brexit was a mistake. Ministers compete to see who can flirt most openly with re-entry, despite their party manifesto pledges not to rejoin the single market or customs union, or to reintroduce freedom of movement.

Keir Starmer has attacked the ‘wild promises’ of Brexit supporters and said Britain must ‘get closer’ to the single market. David Lammy and Wes Streeting have both lamented the ‘damage done by Brexit’ and called for a customs union with Brussels – a proposal that Peter Kyle, the Trade Secretary, suggested would be ‘crazy’ not to consider. Andy Burnham – straying, as is his wont, a little beyond the affairs of Greater Manchester – has gone the furthest, announcing he wants to ‘see this country rejoin’ the EU within his lifetime.

Even as its economy vegetates, the EU’s expansionist ambitions remain undimmed

This federalist footsie is hardly surprising. A recent YouGov poll found that four-fifths of Labour voters want the government to negotiate a customs union with the EU. So do 78 per cent of Liberal Democrats and 75 per cent of Greens. Moving closer to Brussels is an obvious step towards reuniting the left vote; for those interested in Starmer’s job, parading their Europhilia does no harm with Labour MPs and members.

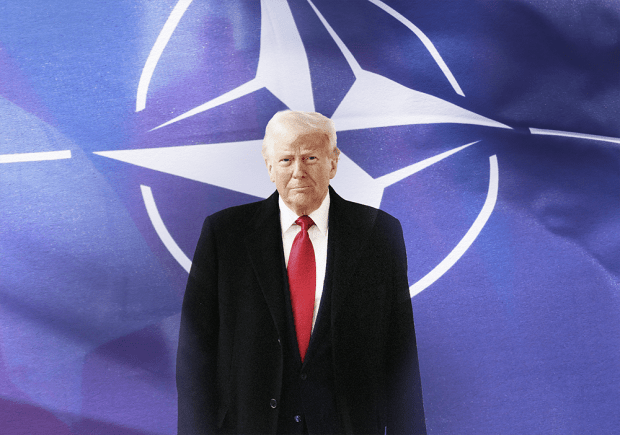

Ministers clothe their ambitions in the language of competitiveness. Reducing trade friction with Brussels would reduce burdens on businesses, even as ministers zealously impose them elsewhere. President Donald Trump’s capriciousness over Greenland makes European solidarity in a volatile multipolar world look comforting. And a thickening of ties to the EU carries few of the moral compromises and security headaches of kowtowing to Beijing, where Starmer has been this week.

But reversing Brexit, however stealthily, would be a mistake – a denial of democracy as egregious as any cancelled council election. Unusually, this is an area in which ministers would gain from listening to Rachel Reeves. At Davos, the Chancellor suggested that Britain could not ‘go back in time’ over Brexit. Despite the starry-eyed hopes of those Europhile Hiroo Onodas still fighting the referendum result, there is no way to restore Britain’s relationship with Europe to what it was on the morning of 23 June 2016. Brexit is a fact.

Rejoining would likely mean doing so without the opt-outs – such as over the eurozone and the Schengen Area. Customs union membership might reduce some UK-EU trade barriers by enabling goods to move between the two with less bureaucracy. But it would mean returning control of Britain’s trade policy to Brussels, wiping out trade agreements negotiated with the US, Australia, New Zealand, India and others.

Enthusiasts now talk about ‘a customs union’ with the EU – a yet-to-be-hashed-out bespoke arrangement – rather than ‘the customs union’. But we already have tariff-free trade, courtesy of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement. Certainly non-tariff regulatory barriers remain. But reducing these would entail rejoining the single market. That would mean accepting EU rules over vast swaths of our economy without a share in writing them, and reintroducing freedom of movement.

Starmer’s so-called ‘reset’ with Brussels is surreptitiously taking Britain back in, piece by piece. Creating a ‘common sanitary and phytosanitary area’ will likely require accepting EU rules on food and agriculture; the proposed ‘youth mobility scheme’ could allow tens of thousands of young Europeans to come and live and work in Britain. With each new concession, Brexit’s justification is undermined.

If Britain is already half-rejoined, why not go the whole hog? Britain is not in fact paying the price for diverging from the EU but from clinging too closely. In our addiction to tax hikes and welfare splurges, costly decarbonisation and excessive regulation, we remain wedded to the approach that has caused the bloc’s stagnation. Ministers show no interest in building on successful departures – such as in gene-editing regulation and scrapping the Common Agricultural Policy – so far achieved.

Yet even as its economy vegetates, the EU’s expansionist ambitions remain undimmed. This week, European leaders discussed building a ‘super Europe’ to act as a counterweight to the US, Russia and China. Such imperial fantasies have been indulged since the bloc’s founding.

But the mooted accession of Ukraine, the six western Balkan countries, Iceland, Moldova and Georgia would add 57 million people to the EU’s population. Were Britain to rejoin, not only would our voice be diminished, but many new-member citizens would have an interest in moving here. And the bloc has also now signed a ‘mobility pact’ with India – a phrase sure to raise the eyebrows of anyone familiar with the so-called Boriswave. One of this government’s few successes has been in reducing legal migration from recent record levels. Ministers who have rolled back low-skill immigration from the developing world should not want to see it reimposed at the European level.

Brexit was a vote of national self-confidence and a liberation from constraints. But the past decade has proved that just leaving the EU is not enough. We require leaders who want to embrace the opportunities of our restored sovereignty, rather than dance a perpetual hokey-cokey around EU membership. Labour’s leading lights do not lack drive. It is our loss that their ambitions are not more purposefully directed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.