I’m lucky. I’ve only visited a family court once, and that was as a journalist rather than a party to a case. One detail stuck with me. On the wall in the waiting area was a poster preparing attendees for the layout of the courtroom: the judge goes here, the barristers go here, and you go here and wait for your fate – for your children’s fate – to be decided.

It was a reminder that, however much family courts have become friendlier in recent years (notably, family court judges stopped wearing wigs in 2008), these are still places that confound and alienate those hoping for justice. That is, whatever ‘justice’ means when the issue at stake is the division of a child between warring parents.

Mothering has often been a tortured question for feminism

Lara Feigel was less lucky. During the pandemic, she ended up disputing custody arrangements with her ex-husband in the courts. It was a bloody business, not only because she lost her case (her daughter remained with her, but her son was sent to live with his father) but also because of how she lost it. She writes:

I was to be held to account by standards I mistakenly believed feminism to have eradicated. I was criticised for being too wilful, for writing books, for owning property; I was told that I wasn’t emotional or repentant enough to be the kind of mother who puts her children first.

Her criticisms are not for her ex, but for the brutality of the process: ‘Custody can drive you mad.’

That experience informs her book, which approaches the subject through the lives of six women writers – Caroline Norton, George Sand, Elizabeth Packard, Frieda Lawrence, Edna O’Brien and Alice Walker – and Britney Spears. All Feigel’s characters are ferociously brave women, though some I found more sympathetic than others. Feigel asks a provocative question: how ‘bad’ does a mother have to be to lose her right to that title?

In 19th-century England, Caroline Norton went through a vicious battle to reclaim her children under a legal system that regarded progeny as property – and property as a male preserve. Judges frequently recognised that by severing the maternal bond they were committing terrible cruelty to mother and child, but the law gave them no choice. Norton’s campaigning improved the situation for other women, but she could not win her own case. ‘I can do what I like with you now, my boy,’ George Norton gloated to their oldest son, having taken custody. Mostly what George liked was to be neglectful. Their youngest son died in a riding accident which Caroline blamed entirely on fatherly in attendance.

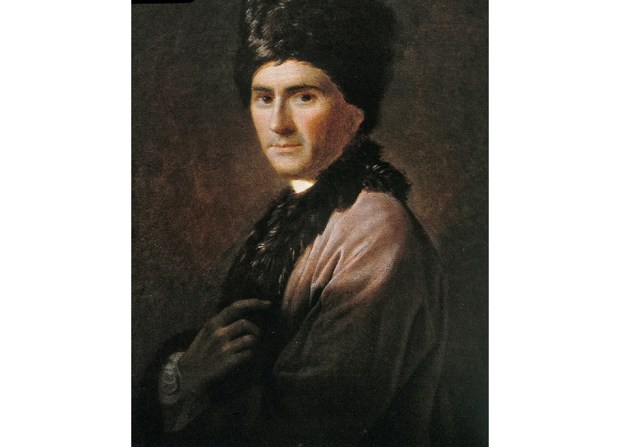

George Sand is one of the most impressive women in the book (despite her lack of formal rights in 19th-century France, she won custody of her children) but also one of the most erratic mothers. As loving as she was, she initially abandoned her children in order to write, and later thought little of lugging them around Europe with her various lovers. Reading this narrative, I flinched over the insecurity these children must have felt, even while I know that Sand’s ‘crimes’ would not be considered crimes at all in a father.

There is undoubtedly a double standard, now as throughout history – one maintained by women as much as by men. Mothering, as Feigel points out, has often been a tortured question for feminism. Norton argued for mothers’ rights from the principle of the intrinsic female capacity for nurturing. I feel a visceral truth in this (who could love my children better than me, the person they grew inside?) even while I’m painfully aware that this position forces an unfair domestic burden on women. As Feigel writes: ‘It is so difficult to reconcile the needs for emancipation and care.’

I’m also painfully aware that not every mother is ‘good enough’. Feigel is sympathetic to Britney Spears, who lost custody of her children after a public breakdown. But you can believe that Spears was treated heinously – by the media, the legal system and her own family – while also entertaining the possibility that at some point her sons might not have been safe with her.

Whose needs should come first? The mother’s, the father’s – or the child’s, which are so often relegated to the bottom of the pile? Pity Rebecca Walker, the daughter of Alice Walker, whose parents came up with the eminently fair system of shuttling her between households every two years. Fair, that is, to everyone except poor uprooted Rebecca.

‘What is a child between wounded parents? Only a weapon,’ wrote Edna O’Brien, who fought for custody of her sons in the 1960s with remarkable dignity. Feigel concludes that every custody case is close to tragedy, whatever the outcome and how-ever necessary the parents’ separation. ‘These children, whose love and hate become subject to the law – we ask too much of them.’ Reading this fine, passionate book, it is hard to disagree.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.