A friendly admonition for the thwarted or struggling writer in your life: that tempting little job at the local bookshop might not be the best way to keep the show on the road until the Muse comes through. Would-be actors who take a front-of-house gig at the National Theatre aren’t constantly buttonholed by strangers raving about how brilliant Andrew Scott’s Hamlet was. Plus, of course, their more successful contemporaries will generally be elsewhere of an evening, doing shows of their own. But imagine slinking out of your modest lodgings, your dreams of what John Tottenham calls ‘actualisation’ left simmering behind you, to spend eight hours wrangling a roomful of people who want nothing more than to chat about – and pay money for – books you know in your heart to be terrible, or fear in some darker recess might be good.

He takes long baths, with classical music on the stereo, a cocktail in one hand and a Barbara Pym in the other

Service is the story of just such a predicament, as experienced by Sean Hangland, a former music journalist born in England but long domiciled in, if not quite reconciled to, America. He is now on the cusp of 50; his creditors are closing in, and he works the evening shift at a lightly fictionalised version of Stories in Echo Park, a rapidly gentrifying district of Los Angeles. His mornings are devoted to a last-ditch attempt to actualise himself in prose, from which he recovers by taking long, rather appealing sounding baths, with classical music on the stereo, a cocktail in one hand and a damp Barbara Pym in the other. Why he feels the need to write in the first place is something that is never made particularly clear, especially considering his low opinion of most people who read.

The book alternates between passages of pithy, misanthropic observational comedy while Sean is at work and baroque interior monologues back at home as he struggles to write, assisted – perhaps less than he thinks – by a pharmacopoeia of ‘yellow’, ‘white’ and ‘brown’ pills. There are a few remembrances of things past and acute observations on LA’s accelerating present along the way – naturally, the bookshop carries a copy of City of Quartz by Mike Davis.

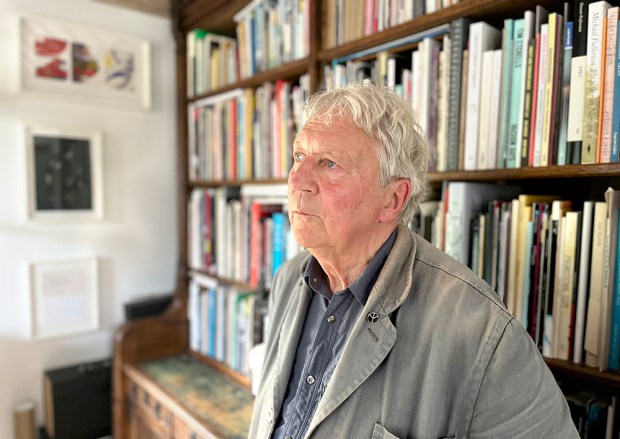

Just how lightly fictionalised a version of John Tottenham (also fiftyish, works at Stories, has ruined good looks, is an authority on country blues, etc) Sean might be is, arguably, moot. Certainly the book doesn’t treat the question with the passive-aggressive shrug one gets from most autofictionalists. We come to understand that the book we are reading is a version of the book Sean is working on. The guy who runs the café at one end of the bookshop even starts giving him notes: sort the tenses out, make the characters more relatable, put in a sex scene (the latter done self-sabotagingly badly: ‘I slowly pounded the shrine of her womanhood…’). The book doesn’t end so much as stop: ‘Then again, fuck it. I’m tired.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.